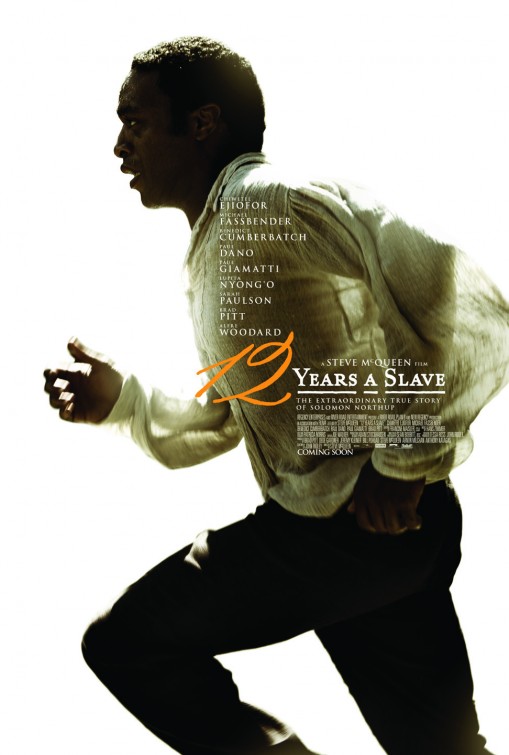

“12 Years a Slave” is masterful. It’s brutal. It’s essential. And it’s likely the best depiction of American slavery on film to date.

But don’t let all those lofty, if accurate, descriptors make you think of “12 Years” like homework—though it will inevitably become the topic of countless college essays over the years. But “12 Years a Slave” is more than the average lsober-minded awards fare. It’s superbly crafted and gritty enough to chill fans of cinema with image after stunning image proving unforgettable.

The film is based on the true-life memoir of Solomon Northrup, a northern free black man in the mid 1800s, played by the exquisite Chiwetel Ejiofor. Northrup had a family, education, skill on the violin and respect in New York society, but almost immediately after the film begins, the title comes to fruition when Northrup is lured into a night of heavy drinking and wakes up shackled in a dark cellar.

As Northrup becomes aware of his captivity, Ejiofor’s face is revealed in just a sliver of moonlight. A sense of dread, injustice, pain and powerlessness that pervades the story begins to take hold. It is the first terrifying moment of the film. But, much like “The Odyssey,” Northrup’s journey away from his family only gets darker and more staggering before any hints of lightness appear.

Northrup is told his legal papers went missing and it is willfully assumed, as one grubby jailer spits in his face, Northrup “ain’t no free man.” The operative words being “free,” but also “man.” Northrup goes on to be treated as property, sub-human, a work machine and even as a source of amusement, always a pawn in the web of disturbed minds that are inevitable when one group of people claims ownership over another.

Northrup is sold at a Washington D.C. market and, throughout the film shifts to three different owners, encountering white men with varying degrees of cruelty. Benedict Cumberbatch plays an owner who seems to want to show some degree of benevolence, while Michael Fassbender convincingly plays a plantation owner known as a “slave breaker” complete with a poisonous brew of entitlement, shame, possessiveness and an unhinged lust for control. Though he can appear to be a monster, the terror has layers. Fassbender’s character’s atrocities are unlike the petty superiority of earlier abuses from a character played by a sniveling, vaguely mustachioed Paul Dano.

That’s one of the key strengths of “12 years.” The characters don’t all react the same way to slavery. In fact, many of the films figures would benefit from close inspection to what each says about the institution. They are individual people and just as the white figures (played by an impressive lineup of famous faces from Brad Pitt, to Paul Giamatti, Paul Dano and Sarah Paulson) can be vastly different in the way they cope with the clear horror they witness or inflict, so too are the enslaved people different with some hoping to die, some finding joys in small freedoms while ignoring the larger indignity and some just trying blend in to avoid further abuse.

For Northrup’s part, he is largely restrained, keeping the emotion boiling under the surface. You can see pain and thought flicker somewhere behind Ejiofor’s eyes or on his expressive brow, but all his restraint and control makes those few moments of unbridled emotion all the more powerful. There is a moment when he permits himself to sing that is particularly affecting.

Beyond the enthralling source-material, to which the film stays fairly loyal, the emotional complexity comes through the filmmaking from director Steve McQueen, known for his films “Hunger,” about the IRA hunger strikes in British prison and “Shame” starring Fassbender, this time as a man crumbling under a gruesome sex addiction.

In this film, McQueen uses all the audience’s senses to create a thick atmosphere to give a sense of place and time.

You may find yourself marveling at the little things. As Northrup wades through a swamp, the color of the algae against the fog is stunning. The sounds of the insects are thick and make you feel the sticky Southern heat.

The lighting is memorable as McQueen plays with careful illumination of each scene and face. In one moment as Northrup looks into a pile of ashes, you just see the gleam of his eyes and shine of sweat on his face. In an emotional moment, that shadowy shot works to reveal the undercurrent of sadness and defeat more than a conventional close-up could ever do.

McQueen holds the camera on each scene for longer than you might expect, especially in the moments of violence and pain. He doesn’t miss the build up or aftermath of things, but rather keeps the camera’s eye steady to see the movement leading into each action and the aftertaste of each consequence. This tactic of refusing to look away extends to the movie’s content as McQueen doesn’t hold back when it comes to showing brutality—though there aren’t that many acts of violence portrayed, those shown are built up to have psychological weight and are shown in vivid detail.

Above all, this movie fills a void, as precious few films take a measured and serious look at what is probably one of the most important moments in American history.

There is a moment near the end of Northrup’s journey when McQueen makes a move known to be risky in film. The man’s face, already marked with scars from years in slavery, shows a search for meaning in a moment of profound desperation. He looks at the sky, side to side.

But then his eyes lock directly on the camera. He is looks at us all watching with such intensity and sadness as if to say “This is your story. You in the theater. This is your history.”

McQueen’s film makes it clear: it’s time to confront our past and look at American slavery in the face.

5 out of 5 stars

By Erin Heffernan