Hurdles for trial

Only on few sexual assault cases on campus are

ever prosecuted, and it’s because it’s not easy to do

April 30, 2015 | Written by Patrick Thomas, Rob Gebelhoff and

McKenna Oxenden; photos by Rebecca Rebholz; design by Theo Syslack

- Marya Leatherwood, Marquette’s Title IX Coordinator, said the university does not pressure students to prosecute sexual assault cases, but will support them if they do.

In September 2012, a man approached a 21-year-old Marquette student near 17th Street and Kilbourn Avenue late in the evening as she headed home from classes.

The man began to touch the woman’s buttocks, even after she told him to stop, according to court records.

Two days later, the same man approached another Marquette student, this one a 20-year-old walking down W. Wells Street around 10 p.m. He reportedly grabbed her buttocks and she tried to pull away, but he then grabbed her breasts.

She eventually broke free, ran away and called police, who arrested the man on the 2600 block of W. Wells, the court records say.

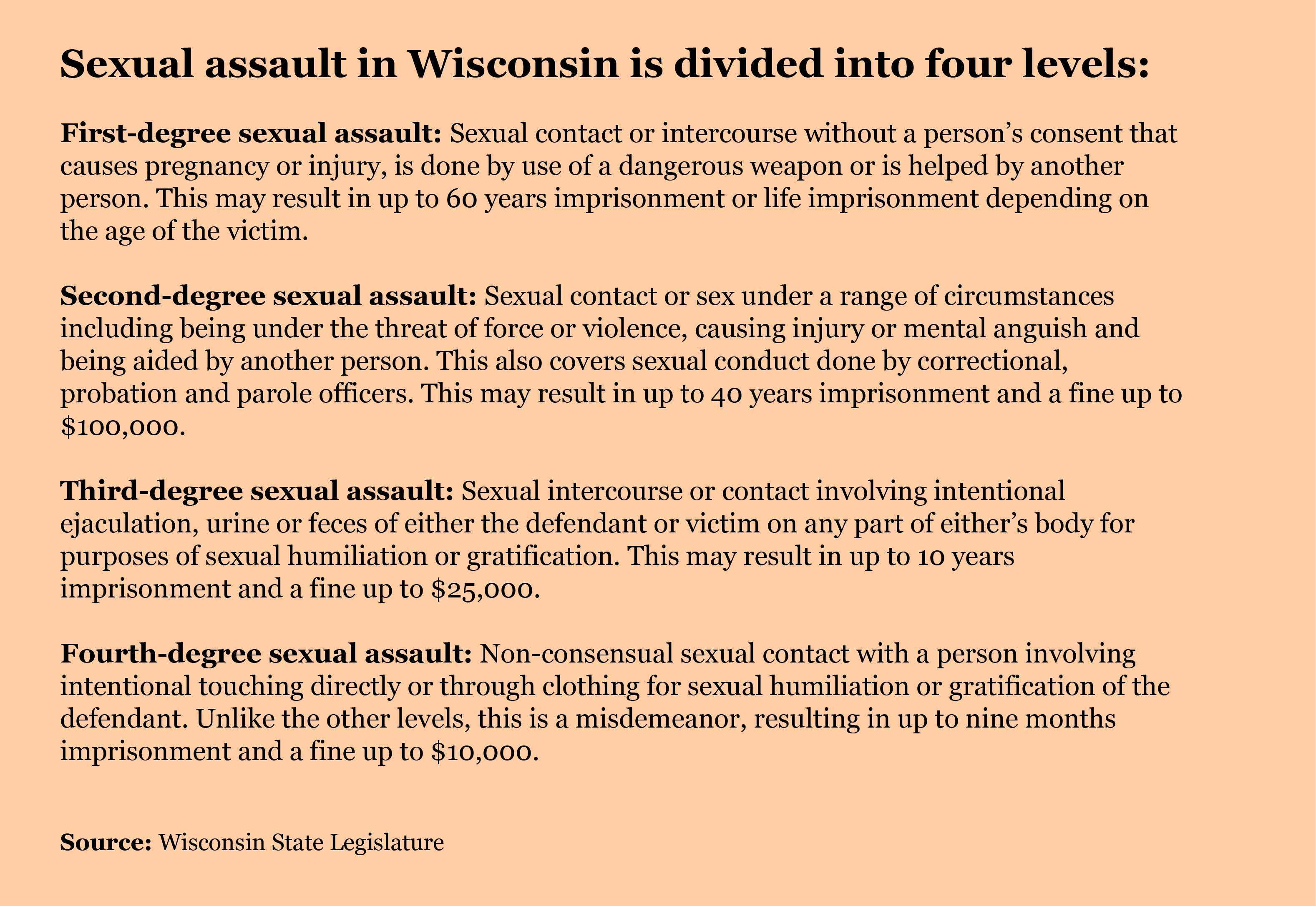

The man was Kendrick Mitchell, a 21-year-old who was eventually found guilty of one count of fourth degree sexual assault and one count of obstructing an officer. He was sentenced to nine months in prison and 18 months of probation, according to court records.

This is a rare case of successfully prosecuted sexual assaults.

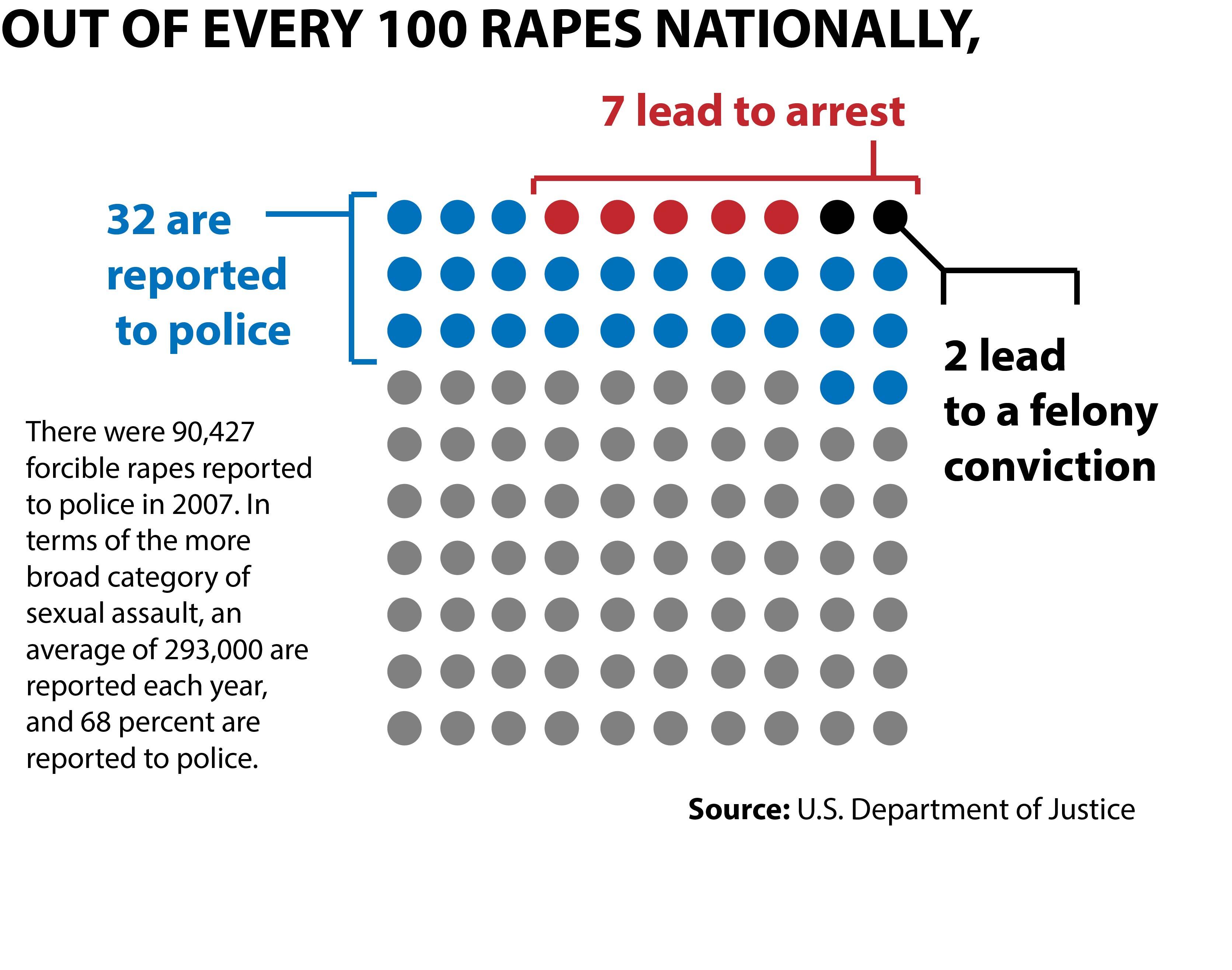

While Marquette reported an average of 19 sexual assault cases a year, only two or three are ever brought to court, said Chris Liegel, head of the sensitive crimes unit in Milwaukee’s District Attorney’s office.

CHALLENGES IN PROSECUTING CASES

When a victim decides to prosecute a sexual assault case, police provide the district attorney’s office with a police report. It is then up to the office to determine if there’s enough evidence for a case.

The report may contain video surveillance, interviews with witnesses and video or audio of the victim’s statements. But this material is hard to come by, as it’s typical for sexual assault cases to have no other witnesses other than the victim and the perpetrator.

Liegel said the fundamental problem with sexual assault cases is that there is often just two statements, one from the victim and the other from the accused.

“Sometimes we have things like text messages or an injury, those kind of things help to break the tie,” Liegel said.

The Sexual Assault Treatment Center at Aurora Health Care is often where the District Attorney’s office gathers more evidence.

“We focus on the patient piece; not every patient is willing to have evidence collected,” said Adam Beeson, a spokesman for the Sexual Assault Treatment Center. “Our first priority is to make sure they are OK and run tests, like pregnancy tests. Our goal is that everyone gets a medical exam.”

But the treatment center faces its own set of challenges. Collecting physical evidence from a female victim can be difficult because most sexual assaults do not result in vaginal injuries for post-puberty women.

“In a jury trial you always need an extra piece of evidence — sometimes motivation can be a tiebreaker,” Liegel said. “We are always looking for that extra piece of evidence to use in trial, like a black eye, or choke marks, but they can be rare and that makes things difficult.”

PROBLEMS WITH CASES INVOLVING STUDENTS

There’s an added difficulty in cases involving college students because, as Liegel said, suspects appear to be “clean cut, young people.”

“The suspect can present themselves in such a way where they don’t look like a scumbag, they don’t look the part of a rapist and can go in front of a jury and say they have a clean record and good GPA,” he said. “Most of the time the victim and the subject know each other and have a casual relationship. It’s rare that it’s a stranger; it’s someone with mutual friends.”

The U.S. Department of Justice reports that 73 percent of people committing sexual assaults know the victim, and 38 percent of rapists are friends or acquaintances.

One of the biggest hurdles to prosecution, however, is the lack of reporting.

There are persistent time lags in getting incidents to police, and in cases when alcohol was involved, victims may fear getting in trouble in the prosecution process.

“They have to admit to underage drinking or marijuana use and will receive a citation,” Liegel said. “If the victim leaves that detail out of their statement, it can be used to attack their credibility and that presents a lot of hurdles in trial.”

A study from the Journal of Trauma and Dissociation found that 16 percent of college students were victims of unwanted sexual contact, but only 2 percent told a sexual assault center or police.

Nationwide, the Justice Department reported that between 2008 to 2012, an average of 68 percent of sexual assaults were not reported to police, and that only two of every 100 rape cases resulted in prison time.

Mascari said Marquette will not pressure students to prosecute if they come forward with an incident.

“First and foremost, it’s up to the victim to pursue it and then the criminal justice process kicks in with the MPD investigating it,” he said. “There will be some cases where a victim might say, ‘I don’t want to go to the Milwaukee Police Department. I don’t want to pursue this criminally. I just want the university to deal with it.'”

Marya Leatherwood, Marquette’s Title IX Coordinator, said the university will only get involved if it knows the accused perpetrator has been involved in other instances. She said there have been a few of these cases in the past, but she was unable to provide any more specific details on these cases, such as how often or when.

“We would try to keep as much privacy as possible,” Leatherwood said. “We wouldn’t divulge (the victim’s) name publicly, but we would, of course, let the victim know that we really do need to take action for safety. I think it’s been fair to say they have understood that.”

MARQUETTE’S ROLE IN CASES

Marquette independently investigates any sexual assault reported to DPS, but it gives police the chance to investigate prior to getting involved.

“We let them take the first run at it and try to develop a case that ultimately an assistant district attorney can take to court,” Mascari said. “When they get to a point in their investigation where us looking into the incident will not adversely affect the evidence and their interviews, then that’s when we’ll start to investigate it.”

The university may take interim steps, such as issuing stay away orders or moving people from classes or residence halls, for the sake of safety.

When a student chooses to take action, DPS has another set of procedures.

The victim will receive assistance along the way from an advocate and a DPS victim witness representative who is knowledgeable of the process. These people can accompany a victim to court proceedings and drive them to the courthouse or police department for interviews throughout the investigation.

It’s then up to the district attorney to review that information and decide if there’s enough information to move forward with charges.

“It’s separate from the process within the university, but in a lot of ways they’re complementary and we work together with the Milwaukee Police Department and the assistant district attorney that’s assigned to the case,” Mascari said.

This is the third article in a three-part series looking into the reporting of sexual assaults at Marquette. Click here to see the rest of the series.