This story is part of an Opinions series focusing on women’s issues.

Feminism is defined as “the belief in the social, economic and political equality of the sexes,” but it is more than this. Feminism is freedom, and if liberation from an oppressive system is the goal, as feminists, we need to focus on liberating all women, not just cisgender white women.

Modern feminism and conversations concerning women’s rights often exclude women of color and our perspectives. This is not shocking, as American feminism is and has always been the tale of the white woman and her heroism; the feminist movement has always failed women of color.

The feminist movement can be broken down into four waves, with the first beginning in 1848 and continuing into the 1920s. The first wave formally began at the Seneca Falls Convention, when both women and men protested in favor of women’s rights For nearly a century, first-wavers marched, lectured and protested, facing grave danger in the process.

But the passing of the 15th Amendment in 1870, which granted Black men the right to vote, turned most white women into suffragettes. In Elizabeth Stanton’s and Susan B. Anthony’s newspaper, a woman said “if educated women are not as fit to decide who shall be the rulers of this country, as ‘field hands,’ then where’s the use of culture, or any brain at all?” which was very deeply ingrained in feminist ideology. Anthony was a known racist and left women of color out of her fight, yet somehow, she was the face of the movement for nearly a century.

Despite the racism saturated into the DNA of the feminist movement, white women only fought for white women’s suffrage as well as equal opportunities to education and employment. And as the movement continued, it shifted its focus to the reproductive rights of women, specifically birth control.

Eventually, in 1920, Congress passed the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote, yet it remained difficult for women of color, especially Black women, to vote. Voting was made difficult due to numerous factors, including literacy tests which most Black women did not have the level of education to pass. Black women looked to the feminist movement to assist them, but this issue was not recognized. This meant that up until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which outlawed discriminatory voting practices, Black women were on their own to combat this issue.

The second wave of feminism began in the 1960s into the late 1980s. It was a reaction to women returning to the roles of housewives and mothers after the end of the Second World War. While the first wave focused on women’s suffrage, the second wave was focused on public and private injustices. Issues concerning rape, reproductive rights, domestic violence and workplace safety were pushed to the forefront and there was widespread effort to reform the image of women in pop culture; women were typically viewed as promiscuous beings, undeserving of respect and boundaries.

And the movement was kickstarted by the publishing of Betty Friedan’s book, “The Feminine Mystique,” a renowned feminist text that gave voices to millions of women’s frustrations, especially middle-class white women.

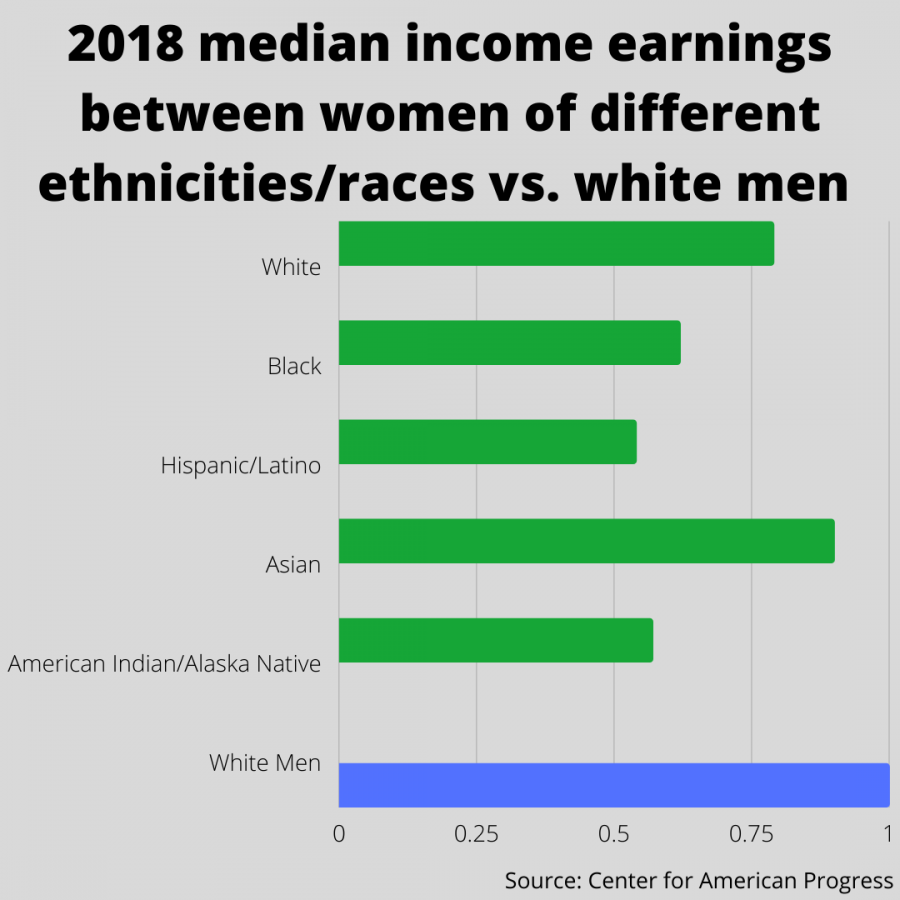

While the second wave had major cultural and legislative progress like 1973’s Roe V. Wade, for example, its shortcoming remained the same: the failure to include women of color. Movements against racism were active too, in which women of color found themselves underrepresented by the feminist movement. Most feminists at this time were middle-class white women who centered the movement around their own experiences while women of color were left out to dry.

Women of color deal with the same issues as white women and more. Due to not receiving the efforts they were giving, during the late 1960s, people of color feminists organized their own movements, one being the Third Women’s World Alliance.

While the concept of intersectionality has gained popularity recently, it was coined by Professor Kimberle Crenshaw in 1989. Intersectionality is the “interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class and gender as they apply to a given individual or group, regarded as creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage.” Women of color do not have the luxury of separating their identities; we are both women and women of color and that comes with its contradictions.

Although few people agree on when the third wave of feminism started, it focused mainly on sexual harassment in the workplace and celebrated major achievements of women which is very similar to the fourth wave, or present-day feminism. And still, like a broken record, women of color and their contributions to the movement fail to be acknowledged.

A prime example is the #MeToo Movement. Tarana Burke, an American activist, started the #MeToo Movement in 2006 to help women with similar experiences stand up for themselves. The movement went viral in 2017, and Burke, like many women of color, found her voice was drowned out by white women.

This narrative is as old as time, and it is time we change it. As feminists, we need to dismantle the idea that working against gender oppression is counter to anti-racist efforts. Next, we need to remind ourselves that liberating women has to include the liberation of all women.

This story was written by Hope Moses. She can be reached at [email protected]