Thrift stores are something I hold near and dear to my heart. I may sound like I’m exaggerating, but really, I know without them, I’d look far less insane. There is truly nowhere else I would be able to find an Edwardian-revival 80s blouse with shoulder pads or overalls that say “old-lady gardening apparel” across the chest.

Ever since I began going to Goodwill with my broke graduate student sister in middle school, I’ve slowly started to exclusively buy from thrift stores. Soon after, I became acquainted with Depop, a reselling site with a user base that’s almost entirely under the age of 26. It’s easy to use and perfect for harder-to-find vintage pieces.

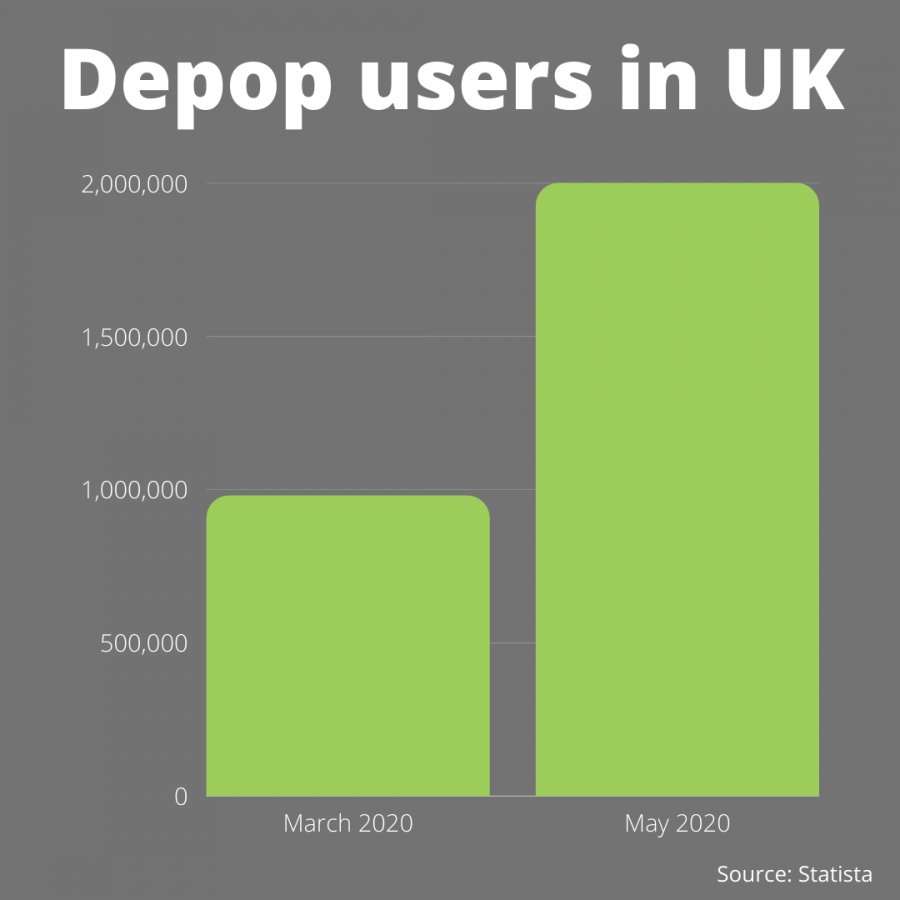

Depop has sharply risen in users since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the United Kingdom, where the resale company is based, the number of active users doubled from 980,000 to 2 million from March 2020 to May 2020, according to a Statista report. The company had been steadily on the rise since 2011, but now Depop is a household name for much of Generation Z.

It is important to be aware of how reselling can impact lower-income people who rely on thrift stores, and important to learn how to weed out scammers like drop-shippers, who mark up and advertise a fast-fashion product as their own and then send their customers items directly through the retailer. The new world of thrifting and reselling is a controversial one, so consumers must be conscious of how their buying habits impact the industry as a whole.

I’ve come across children’s T-shirts put up for $50, scuffed and cruddy Vans selling for their original retail price and drop-shippers with clearly stolen photos from fast-fashion sites. Some sellers will even purchase from higher-end retail lines for the sole purpose of reselling it for double the original price.

None of this is new, as vintage resellers like antique stores, and sneaker resellers specifically, have been around for decades. However, the online marketplace makes it increasingly easier for everyday users to set up a resale side business, myself included.

I tend to use thrifting as therapy sometimes, as the methodical action of going through clothes and instant dopamine release when I strike gold is nearly addicting. My style also changes by the minute, so I tend to go through clothes fast. Reselling is a really easy way to make a little extra cash with pieces I’ve stopped wearing, and I sleep better at night knowing that my old favorites are getting some more use out of them.

While that’s all great, there’s also the guilt of knowing I could simply donate it all back to the stores I bought it from. Although I barely mark up my items, I still feel a bit guilty — I’m not sure if it’s ethical to go into a space made to be affordable and then make it less accessible to those who can only buy secondhand. I wonder if even by using the platform I’m contributing to the gentrification of thrifting, as some have called it.

Gentrification was initially coined to describe the phenomenon of middle and upper-class people moving into working-class neighborhoods which increases up the cost of living and forces working-class people to move out. Recently, the word has been applied to encompass a broader array of topics. Thrift store gentrification not only refers to rising prices at thrift stores but also the way people perceive it. When working-class people were thrifting, it was considered cheap and unsanitary. Now that middle-class teenagers have started doing it, thrifting has become trendy.

Goodwill specifically has changed their pricing system from past years to include a wider range of prices, so now employees can judge the quality or brand of an item and price accordingly. This has led stores to mark up stylish and durable items, making them inaccessible to many people who thrift.

Then again, there are so many upsides to the resale market. Fast fashion is not only an environmental problem but also a human rights one. Brands like Shein, Old Navy and Forever 21 are responsible for 8% of carbon emissions, and 93% of fast-fashion brands do not pay their workers a livable wage. Consumers are able to avoid that completely by buying secondhand, as long as they can avoid the drop-shippers of Aliexpress, which is an infamous fast fashion seller.

Furthermore, over 84% of clothing ends up in landfills and thrift stores have to throw away some merchandise to make room for the new donations. A lot of clothing ends up in rag houses, where “clothes go to die,” according to vintage reseller Madeline Pendleton. Resellers are able to give new life to old clothes by reselling, or as Pendleton does, reworking them into new pieces.

There are ways to be ethical about reselling and thrifting in general. My main rules are no buying work clothes or winter gear, no marking up more than what I know an item is worth and no overconsuming second-hand clothes the way we’re expected to consume fast fashion. The last one has been difficult for me, but I’m finding I appreciate my clothes more as I visit thrift stores less often.

By fighting our consumerist tendencies and considering how our purchases impact others, the thrifting movement can help create a more sustainable and humane fashion industry, rather than a gentrified one.

This story was written by Jenna Koch. She can be reached at jenna.koch@marquette.edu