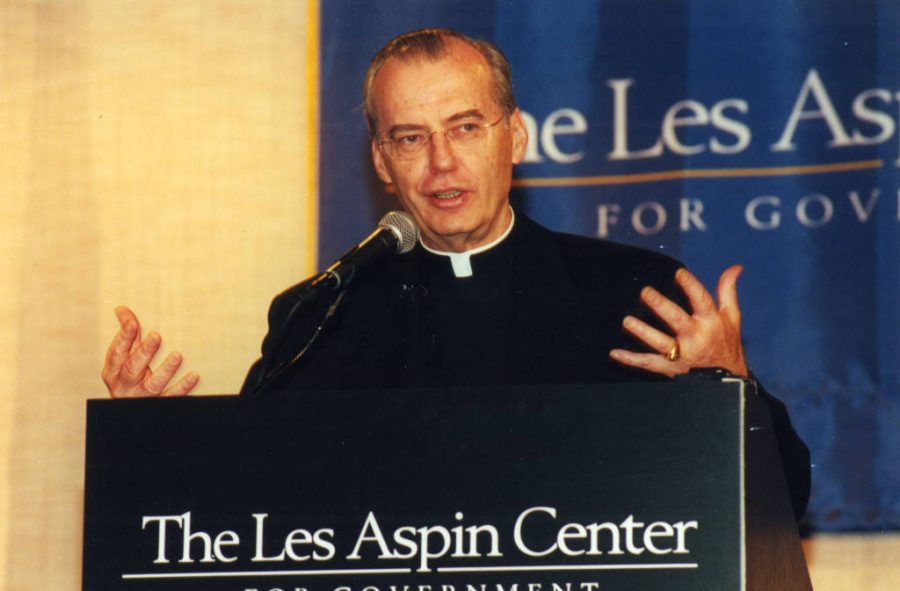

A previous Marquette Wire investigative report published March 7 found that multiple Title IX cases dealing with sexual harassment had been filed against Rev. Timothy O’Brien, a Marquette priest, professor and founder of the Les Aspin Center program. The Marquette Title IX office confirmed that two cases are still ongoing today.

“I emphatically deny these allegations,” O’Brien said in an email. “While this matter is pending, it would be inappropriate for me to comment further as I do not wish to influence or impede the efforts of Marquette University in its investigation. Due to ongoing complications from a recent accident, I am currently on medical disability leave consistent with my doctor’s recommendation.”

But while these allegations have been denied by O’Brien, the cases have sparked change and surprise for many Marquette students, staff and faculty, especially those in the Les Aspin program this spring.

Until the morning of March 7, the students in the Washington D.C. program were not aware that O’Brien had been living in the Les Aspin Center.

“No one knew in terms of no one said anything about it to us,” an anonymous student in the College of Arts & Sciences, said. “We had assumed, but it had never been confirmed. No one ever came out and told us who O’Brien was, that he was living here, that he was on medical leave, anything like that.”

The student wished to be anonymous, as they are still currently in the Les Aspin program this semester. While they said the class could sometimes hear when people were upstairs or in the living room area of the center – and would occasionally see O’Brien walking his dog – they were not sure who he was or where he was living.

“They never told us that any of this was happening when we came to D.C., and obviously they couldn’t because of some confidentiality reasons, but it would have been nice to know that he is still living there, because he is still in the building and students still occasionally see him around,” they said.

Christopher Murray, interim director of the Les Aspin Center, sent an email to the spring cohort, responding to the report. The statement read:

“I imagine there may be feelings of frustration, anger and sadness among the group. I want you to know that I am available to you and will answer whatever questions I can, but also know that there may be questions that I cannot answer due to confidentiality requirements. I want to assure you that our first priority is the well-being of all of you and that we will continue to provide you the best academic, internship and residential experience possible.”

He also provided resources for the university’s bias response team and the Marquette Title IX processes. The student said this was the first time O’Brien’s name was acknowledged.

“To echo Chris’ note, my greatest concern is always your well-being as students here at the Center,” Ally Glasford, coordinator of student life and administration for the Les Aspin Center, said in an email to the spring cohort. “If this news is bringing up discomforting or confusing feelings, I am here to support you however I am able.”

The following day, March 8, Murray and Glasford sent another email, offering to meet with students the following Monday, if anyone was interested.

“We had heard rumors. I think everyone’s heard rumors, especially the people who decided to go to the Les Aspin program,” the student said. “It was just kind of nice to see some of those rumors being dispelled because I’m sure things get out of hand, but also just for things to be confirmed and know that at least the university has to kind of do something about it now that people actually know.”

Back at Marquette

Back on Marquette’s campus, the university — some faculty, staff and students — responded to the news with support for the students and other members of the Marquette community.

“We are deeply disturbed by the developments described in the article and want you to know that student’s well-being is our top concern,” Paul Nolette, political science department chair, said in an email to all political science and international affairs students. “These developments also make clear that significant changes at the (Les) Aspin Center are necessary.”

Nollete said the department had been already been in the process of hiring a new Les Aspin Center director.

“However, much more needs to be done, and students will be critical in finding solutions,” Nolette said in the email. “We want you to feel comfortable sharing with us your experiences and ideas for the Center moving forward.”

Marquette University President Michael Lovell and other university leaders also met with the students in the cases — David Chrisbaum, a senior in the College of Arts & Sciences, and Amanda Schmidt, a junior in the College of Arts & Sciences — to hear their concerns and discuss potential changes together.

Standing by O’Brien

But while many showed support for the students involved in the Title IX cases, some also shared sympathy for O’Brien.

After hearing about the sexual harassment cases filed against O’Brien, Alex Johnson, a 1993 Marquette alum, said he was unsure what to make of the situation.

“I think that people (college) age are victim-seekers and I think that people find offense very easily these days,” Johnson said. “I’m not saying what happened to (the students) wasn’t offensive, but I think people find offense very easily.”

Johnson said it is hard to judge what happened without knowing the full context or hearing the conversations when it happened, and putting your hand on someone’s back can be interpreted a number of different ways.

“It can be a completely innocent act that happened. It could be something that somebody interpreted as an offensive act, and if somebody is older, the interpretation may have gone the other way,” Johnson said. “I know he liked to use humor, and so the question is to what extent these conversations were either taken the wrong way or interpreted the wrong way or interpreted the right way.”

When Johnson had O’Brien as a political science professor at Marquette between 1989 to 1993, he said he was never afraid to ask hard questions or challenge his professors. While Johnson did not attend the Les Aspin Center in Washington D.C. — as he grew up there and wanted to spend time exploring new places away from home — he had O’Brien as a professor several times at Marquette, including courses on interest groups, religion politics and the U.S. government.

While Johnson said he leans more conservative, he thinks O’Brien was more center or left-of-center politically.

“Some people enjoy sparring and disagreement and conversation, others stray from it. I enjoyed it,” Johnson said. “I like to represent my philosophical, political viewpoint, so that’s what I did in class. In a lot of classes, that was a minority opinion, but I enjoyed having those discussions.”

Johnson said he thinks O’Brien appreciated hearing those different viewpoints and perspectives. The political classroom debates and polar viewpoints eventually led to a long-time friendship between Johnson and O’Brien.

“There are hundreds of people, if not thousands, who have been helped by the work (O’Brien) did by creating the Les Aspin Center,” Johnson said. “I mean it was his sheer force of will to come to D.C. and start with a summer program and then eventually make it into a year-round program and fund it with building and classes and a residence hall.”

Johnson said he has kept in touch with O’Brien over the past 30 years, whether it was participating in fundraising dinners or events, grabbing lunch or just connecting every now and then.

“I think the program is great because it exposes a lot of people who aren’t from D.C., and who didn’t grow up in politics, to a political system,” Johnson said. “What it’s like to live in D.C., what it’s like to interact with people at the highest levels of government, to learn that craft, to learn the legislative process, to learn the lobbying process, to learn all of that, I mean I think is invaluable. It’s an invaluable part of what the program does.”

After graduating, Johnson worked in politics — working for Republican leaders like Mitt Romney, John McCain and Jack Kemp in the 1990s and 2000s — before transitioning to state lobbying. He also formerly worked for the Republican National Committee and has created the Republican Legislative Campaign Committee. He now works for instate partners.

Johnson said he has since contributed to the Les Aspin Center both financially — with occasional donations — and by connecting students to internships or employment opportunities around the capitol.

“I appreciate the time that I had to spend with O’Brien and I think hundreds of others would have the same opinion that he taught us a lot about the world, about politics, and for that I am grateful,” Johnson said.

Johnson said he hopes can continue to keep in touch with O’Brien.

“The worst people in the world are those that leave you when things get tough,” Johnson said. “I hope the Title IX process works out for him. I hope that he finds a soft landing somewhere that he can live out his years and continue his service that he’s done at Marquette and for others and that he’s happy. Those are the things that I wish the most for him.”

As for the Les Aspin Center, Johnson said he hopes it continues to grow and be a prominent part of the Marquette and Washington D.C. community.

Policy Changes

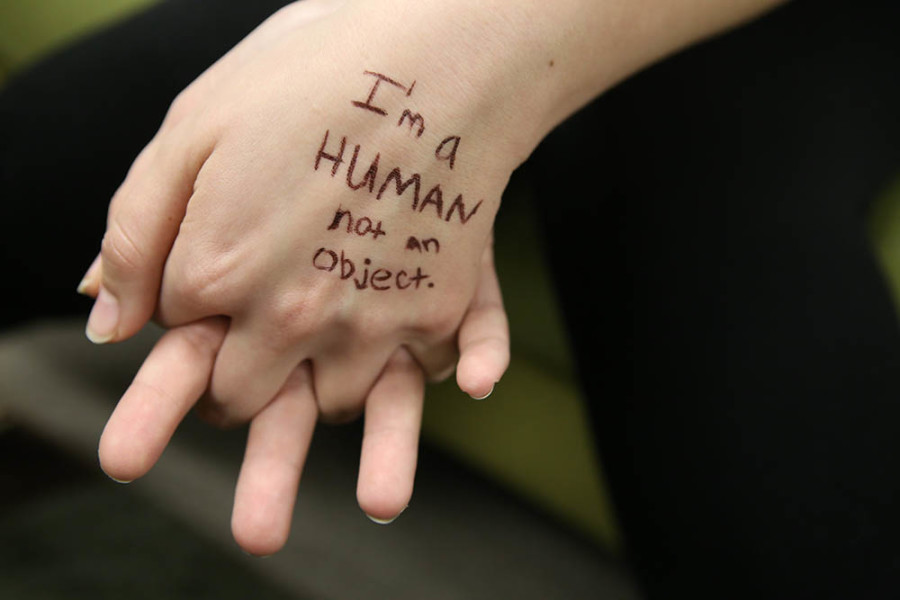

Schmidt and Chrisbaum said the updated set of Title IX regulations, which were created by the U.S. Department of Education under the Trump Administration May 6, 2020, have made the Title IX process even more emotionally difficult.

“The thing with this is I, in no situation in which I was with (O’Brien), was traumatized in any experience,” Chrisbaum said. “I felt uncomfortable, it was weird, I’ve never had a professor act like that with me. What was traumatizing for me, was the report I had to read that went on for 20 pages about how terrible a person I am.”

Chrisbaum said the legal language changes made it a requirement to read the full transcript of everything O’Brien said and wrote about him in the report. He said the changes have also made it increasingly difficult to understand the fine lines of what constitute a Title IX case, and for students to fully know their rights.

Title IX itself is a single sentence: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

However, while the current legislation is contained in a 2,033 page document, the Obama administration’s rule was 53 pages and the Trump administration’s first pass was 38 pages. This is nearly a 2,000 page difference in the written rules of filing a Title IX case.

For example, the new rule has limited the types of sexual misconduct universities are required to investigate to actions that are “severe, pervasive and objectively offensive.”

Schmidt said she argued that her case was pervasive, as she had heard other students brought cases against O’Brien as well, and argued that the rules do not have to apply to just one person.

The Trump administration also requires those filing to go through a cross-examination in a live hearing, bringing them face to face with their alleged perpetrator. The only other option is to go through an “informal resolution,” making participation in the Title IX process voluntary for both parties. This means that if an alleged perpetrator does not want to participate in disciplinary proceedings, they have the right to refuse.

While Chrisbaum and Schmidt’s hearings have been pushed back twice due to O’Brien’s medical leave, their current hearing date is May 19.

Chrisbaum was also one of the students asked to sit in on the search committee’s interviews for the top three candidates for the next director of the Les Aspin Center. The next director is expected to be announced the end of the school year.

This story was written by Skyler Chun. She can be reached at skyler.chun@marquette.edu