James Wright Foley dedicated the last years of his life to exposing humanitarian crises in the Middle East. The photojournalist worked countless hours providing in-depth coverage of the Libyan and Syrian civil wars and their civilian casualties. He faced captivity twice, spending more than two years as a hostage in total. Eventually, he paid the ultimate price in an act of terrorism that shocked the world.

James Wright Foley dedicated the last years of his life to exposing humanitarian crises in the Middle East. The photojournalist worked countless hours providing in-depth coverage of the Libyan and Syrian civil wars and their civilian casualties. He faced captivity twice, spending more than two years as a hostage in total. Eventually, he paid the ultimate price in an act of terrorism that shocked the world.

His task was one that few journalists would be willing to endure, yet his story was never fully publicized, perhaps on account of his own humility. Nevertheless, it’s a story that deserves to be told in order to better understand better his dedication, bravery and faith, a lot of which he attributed to his time at Marquette.

In the fall of 1992, 18-year-old Jim Foley left his home in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, and moved into O’Donnell Hall, an all-male freshman dorm on the west side of Marquette’s campus. He brought with him an appetite satisfied by any dorm cafeteria food; he wasn’t very picky. He had a bad habit of borrowing other people’s clothes. In his free time, he played rugby or goofed off with friends.

“Oh no, I can’t,” laughs Dan Hanrahan, as he thinks about the practical jokes his friends pulled as undergraduates. “Well, I can say, I will not directly attribute this to Jim, but one night, he disappeared for a while, and the next morning, the ‘TRI’ from the Triangle Fraternity letters were missing. It was just called the ‘ANGLE’ fraternity.”

Hanrahan (Eng ’97, Law ’00, Grad ’10) lived on the same floor as Foley in O’Donnell Hall, and they became close when both joined the rugby team. Soon, he and the “funny, goofy kid from the East Coast” joined a tight-knit group of friends that would support each other like brothers for almost 20 years after graduation.

Their familial affection even transcended chastisement from the university. When one of their friends got into a “scrape,” which Hanrahan will neither confirm nor deny involved driving into a light post, Foley took the blame.

“He raised his hand and took the heat for one of his friends. It’s an anecdotal story, but it really demonstrates Jim to the end,” Hanrahan says. “Maybe that’s not a great lesson for a student, but his dedication to his friends and willingness to step up and protect others, that quality showed through to the very end.”

His fervor to stand up for others sparked his interest in social justice, which eventually turned into a calling to study journalism. Foley considered leaving his history track to transfer into the Diederich College of Communication, but Marquette’s journalism curriculum would have required him to stay in school for an extra two years. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in history in 1996.

Foley went on to work for Teach for America, where he volunteered at Lowell Elementary School in Phoenix, and later taught inmates in Chicago at the Cook County Sheriff’s Boot Camp. But his desire to report on conflicts surrounding social justice never faded. He returned to school, this time at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism. According to Ellen Shearer, who taught Foley in Medill’s Washington D.C. program in 2003, reporting overseas was always his goal.

“Jim felt very strongly that it was important to be covering the wars at that time in Iraq and Afghanistan,” Shearer says, “that he wanted to be a journalistic witness to what was going on and tell the stories, and from there, he just continued covering conflicts.”

The danger associated with his newfound profession finally manifested in 2011. While reporting on uprisings in Libya for the GlobalPost, Foley was captured by pro-Gaddafi soldiers, who confined him to a 12-by-15-foot prison cell for an agonizing 44 days. Journalists Claire Gillis and Manuel Varela were also captured; a third, Anton Hammerl, was left for dead, bleeding in the hot Libyan sun.

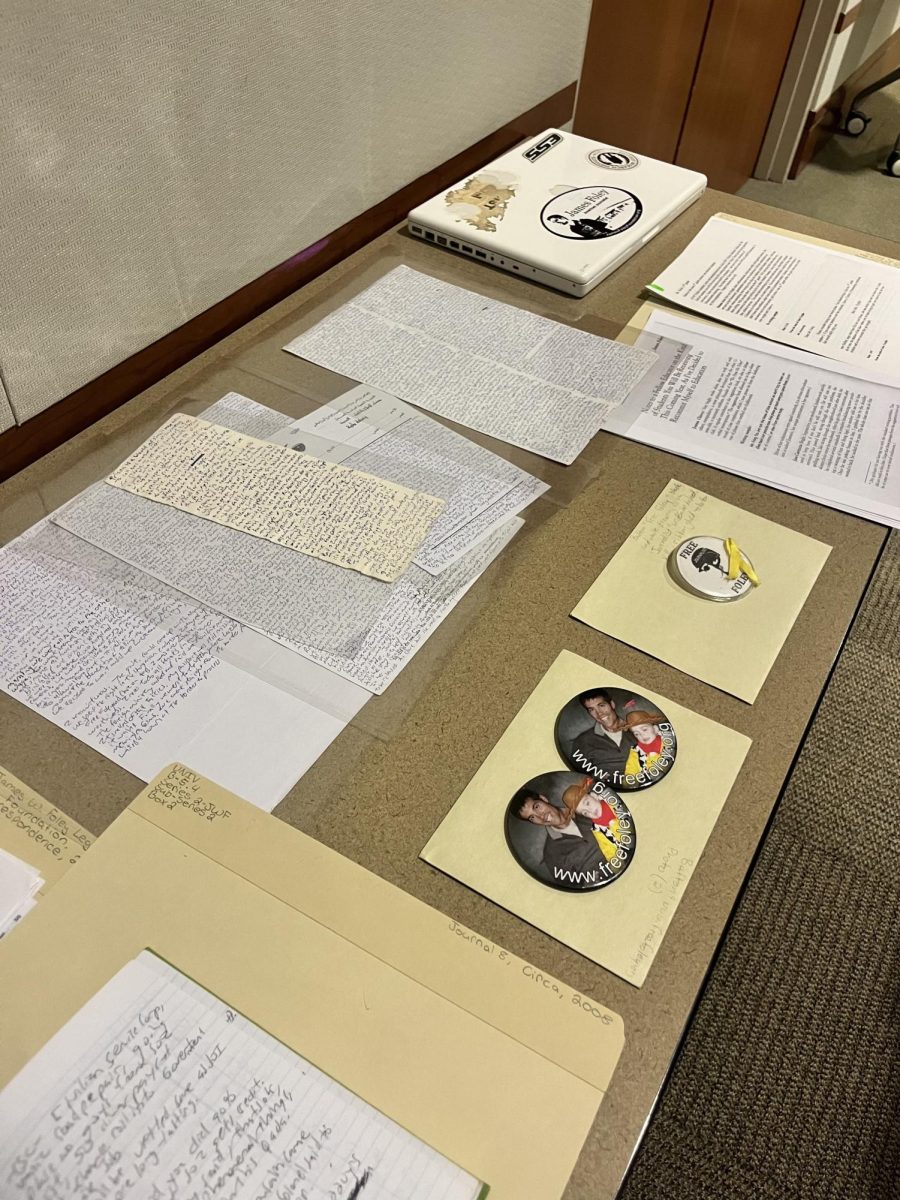

Stateside, family and friends started the Free Foley campaign through media outreach and online resources. It quickly garnered national attention and even made its way to other countries. The group hoped to get 25,000 signatures on a petition for his release. The final tally neared 35,000.

“That’s how Jim was,” Hanrahan says. “He brought all different people together in many different manners.”

Foley returned to his alma mater later that year after his release. Dr. William Thorn, an associate professor of journalism, remembers watching Foley speak at a panel on war coverage and thinking him a drastically different man than the student he saw years before. Noticeably more reflective and somber, he talked to students about the importance of prayer during his captivity and his decision to go back to the war-torn region.

“I thought he seemed slightly naive about the risks he was facing going back,” Thorn says, “but he had a lot of confidence he could handle it. You could hear it in his voice.”

His resolute demeanor revealed what Foley felt was a responsibility to finish what he had started, telling the stories of civilians in belligerent countries who otherwise had no voice. Some asked if it were foolish to go back. He dutifully replied, ”I can take it. I’m strong.”

“His decision was that he needed to (practice) journalism,” Thorn says, “because that was the way to change injustice, by making it visible.”

Foley’s death was arguably the most visible form of the injustice he desired so desperately to end. On August 19, almost two years after Foley’s second capture in November, 2012, Islamic State terrorists released a graphic video titled, “A Message to America.” In it, Foley is seen kneeling in a desert as he tells his family and friends to “rise up against my real killers, the U.S. government.” An unidentified man dressed in black then executes him, demanding President Obama to stop air strikes in Iraq or Time magazine contributor Steven Sotloff would be next.

The loved ones who actively campaigned for his release staggered in the sudden, tragic loss. Through the confusion and depression in the days that followed, they tried to make sense of the situation, piecing together what little information they had, thinking of what Jim would do.

“I said to myself and later said to my friends that he would not just sit around and feel bad,” Hanrahan says. “That’s obviously part of the grieving process, and you’ve got to do it, but he would also want to do something that would make the situation, the world better because of something. (We had) to carry on that spirit and really what Jim brought to the world so that that light wasn’t snuffed out at that moment, that it would continue on for generations.”

A scholarship seemed most fitting to carry on Foley’s legacy. Hanrahan and Marquette alumni Tom Durkin and Peter Pedraza reached out to Marquette to create the James Foley Scholarship Fund with Foley’s parents, Diane and John. Once the fund is completed, it will be awarded to a student in the Diederich College of Communication who embodies Foley’s ideals and dedication to his craft.

The effort quickly gained national attention through various websites and spokespeople. Broadcast journalists Katie Couric and Anderson Cooper both promoted it on their personal Twitter accounts in the days following Foley’s death. Esquire magazine organized a fundraiser on Sept. 11, asking for donations from anyone who read its online feature, “The Falling Man,” that day to contribute to the fund. Neither financial statistics nor a time frame saying when the scholarship will be offered are available, though fundraising efforts are said to be successful so far.

“The support to that fund has come from individuals across the country and even some from outside the country,” says Andy Brodzeller, associate director of university communication. “Many of those individuals haven’t donated or supported Marquette in the past, or had no connection to Marquette, so they really are giving to support what Jim did and what he stood for.”

Even people who had no personal connections to Foley started their own memorials. Documentary photographer Daniel van Moll started following the photojournalist’s work in 2011, though the two never met. Van Moll was on assignment in Zambia when he heard news of Foley’s death. Nevertheless, he partnered with other photojournalists to build www.rememberingjimfoley.org, a site where people can post pictures or messages in memoriam. It reached about one million people during the first five days after its launch and continues to grow.

“Submissions just won’t stop, and we are overwhelmed by the participation of friends and supporters,” van Moll writes in an email. “Even people that never met Jim in person contributed from all over the world.”

The supporters behind these efforts, his loved ones and those he inspired with his work and steadfast commitment to his vocation will ensure the legacy of James Foley lives on.

“Even though he’s gone from this earth,” Hanrahan says, “while we’re here, his friends and family, we’ll continue to try to live on in a way that would carry on from his ideals, at least make him either proud or laugh.”