Slasher staples like “Halloween” or “Friday the 13th” are favorites around this season, both for their infamous killers and derivative plots. But as cheesy as these movies may seem, they serve as an indicator for the culture surrounding the time period in which they were produced.

Alongside the rise of the slasher in the 1970s and 80s was a resurgence of purity culture. Following the counterculture movement, which included the sexual revolution and the rise of drug use in the 1960s, a reactionary movement spread across the United States.

Many older Americans demanded something must be done to restore traditional relationship structures and discourage experimentation with drugs. This sparked political activism like the nationwide “Just Say No” campaign, backed by First Lady Nancy Reagan, as an attempt to decrease drug use among young people.

With the movement having a major influence on politics and media at this time, it was no surprise that it eventually spread to the movie screen. This led to the creation of the “final girl” trope.

The final girl is the main character who survives to the end of the movie while her friends get picked off by the killer. But a final girl is not the designated survivor because she simply outsmarted the masked maniac. Final girls in this period are almost always opposed to having sex and using drugs, while her friend group seems to believe the exact opposite.

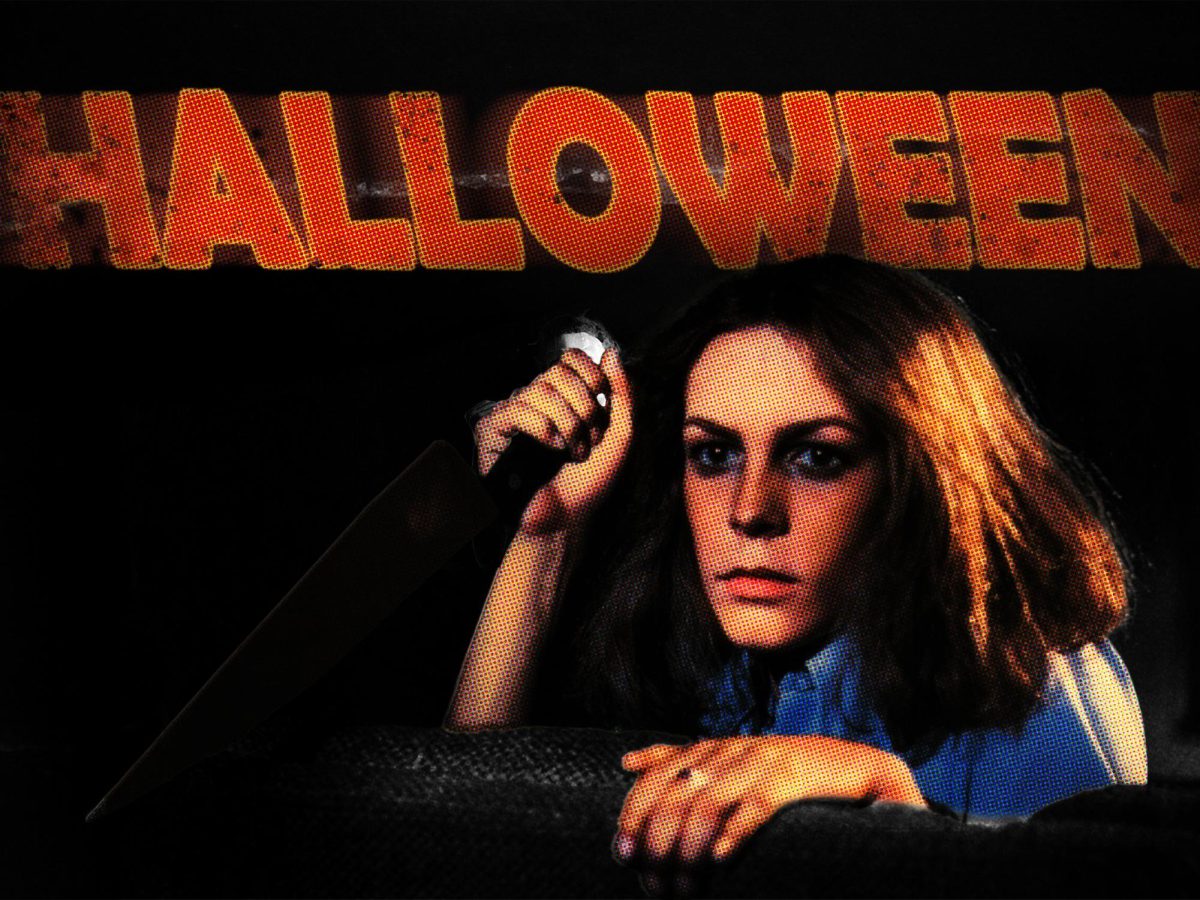

For example, Laurie Strode, played by Jamie Lee Curtis in “Halloween” establishes herself as more traditional than her friends from her first few scenes. As the movie introduces us to her and her group of friends, we can see how she is different, wearing a modest long skirt while her friends Lynda and Annie wear pants.

While she does occasionally use marijuana in the film, she is not as frequent of a user as her friends are, and when night falls and the girls all start their babysitting jobs, Annie leaves the kid she is supposed to be responsible for with Laurie to go have sex with her boyfriend. She never even makes it to his house because our masked killer Michael Myers is waiting in her backseat.

It is writing like this that seems to convey to the audience that on some level, these characters deserved what was coming to them. An action like shirking her babysitting duty to go see her boyfriend proves that Annie was an amoral person who was rightfully targeted by the killer.

There is much debate on each respective director’s intentions with using these themes. Some argue that many of these directors were themselves subscribers to the idea that purity culture should be reinstituted in daily life.

Others believe that these directors found the concept of purity culture humorous and had those who engaged in recreational drugs or sex gruesomely killed in their movies as a way of commenting on how absurd parents were treating these topics.

But I believe that these directors did as all good directors should and tapped into the fears of a generation. As the idea of individual freedoms for teens changed after the counterculture movement, and suddenly there were new responsibilities on the minds of many young adults, directors took advantage of the fears that came with these responsibilities.

While not taking themselves too seriously, these directors created a story where young people could both laugh at the hilarity of the stereotyped young characters, while allowing them to consider the fears they confront while getting older and gaining new responsibility in a new era of sex and substances.

This story was written by John O’Shea. He can be reached at j.oshea@marquette.edu.