Laurie Kontney, a former physical therapy professor at Marquette and a Muskego-Norway school district member, has found herself in some hot water with her new occupation.

Since the start of her new job, she influenced the removal of a book from the curriculum.

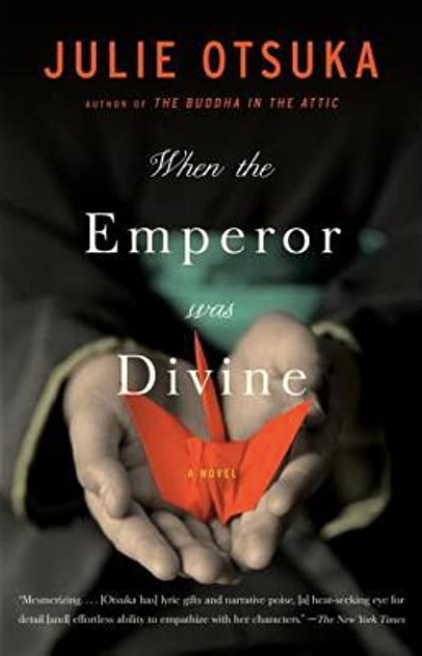

The book in question is “When the Emperor was Divine” by Julie Otsuka, a story that goes into the U.S. government’s incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Kontney’s reason for the literary exclusion was that themes in the book didn’t have a place in English class.

Parents have taken a stance and think this is classroom oppression, with more than 300 signings on a petition asking for the return of the book to the curriculum.

Laurie Kontney could not be reached for comment.

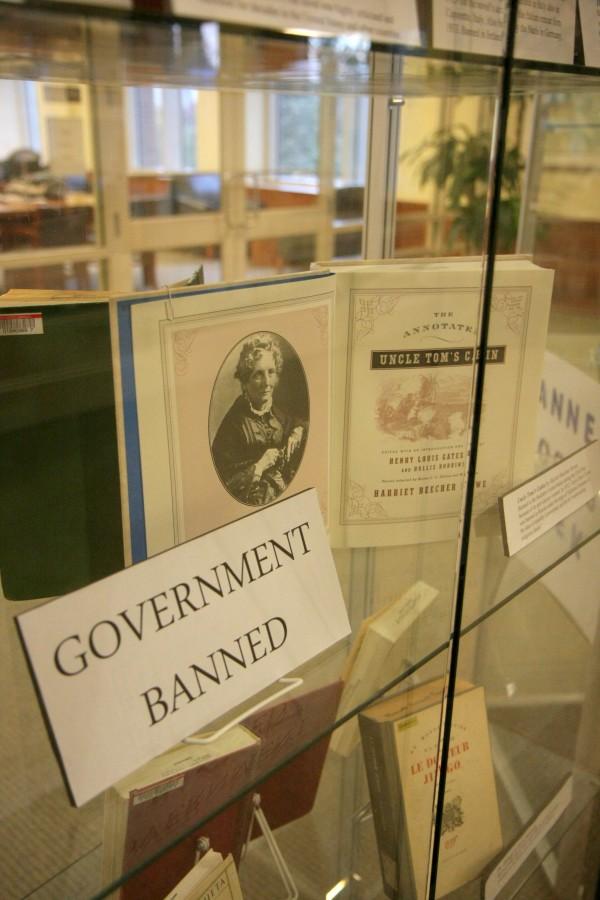

This Sunday, Sept. 18 marks the start of Banned Books Week, a week of awareness on censorship in forms of print media, while also supporting students, educators and publishers.

This classroom oppression is one of many modern instances where teachers are restricted from teaching specific subjects in the class.

Back in January, the Wisconsin senate passed a bill looking to ban critical race theory from being taught in the classroom. Critical race theory is the idea of how rulings in the court system influence people negatively in a certain societal class. The bill was then vetoed by Governor Evers.

So far there have been eight states to pass legislation banning talks of CRT in the classroom, with many other states planning to introduce legislation of their own.

The most notable of these laws passed is the Stop WOKE Act introduced in Florida, which prohibits the hiring and discussions of CRT in education.

Juniper Colwell, a philosophy professor at Marquette, said that many times these fears of CRT in the classroom are blown up without any reason.

“It’s kicking up a lot of fears on the way education is being used with topics that are really milk and toast, basic, inclusiveness type things,” Colwell said.

Erik Ugland, associate professor in the College of Communication, said this inflation has created a bigger concern of hysteria, diluting what teachers are instructing in their classrooms.

Ugland said he believes that CRT’s use in modern politics has become a “boogeyman term” used to scare away further discussion on the topic and teachers who are trying to inform students on issues concerning race in society.

He added that this will only end up hindering students’ development, limiting their perspectives on concepts that are outside of what they are exposed to in their everyday lives.

“Learning about these things is an important part of American history and is not preparing students for the real world,” Ugland said.

Bridgeman Flowers, a junior in the College of Education, said that removing diverse content in the classroom makes it difficult for students to relate to other world perspectives.

“As people we are supposed to see through other people’s lenses. Not being able to do that allows us to be socialized to believed that one lens is the only lens,” Flowers said.

Ugland said he fears the suppression of perspectives in the classroom could lead to single-minded students with a lack of individualism.

Jadzia Fitzgerald, a junior in the College of Arts & Sciences, said the school system is responsible for introducing youth to topics they wouldn’t normally be familiar with. She added that classroom manipulation removes important information in certain subjects which causes students to think less critically about what is being taught.

Alexis Bickerstaff, a senior in the College of Education, said the school system is in power of creating the stories, and deciding what kind of stories are expressed. She fears that the silence in classrooms has created a contentment in the system.

“People from the outside looking in aren’t able to speak up. How can we speak up when they shut everything down? Or when they chose what is being put out into society? We are trying to say that, but they aren’t listening,” Bickerstaff said.

Colwell said the true meaning of CRT has been obfuscated by politicians.

“Nowadays critical race theory has become this kind of blanket term that you can throw onto all these vague ideas,” Colwell said.

The term “Critical Race Theory” was introduced in 1989 in Madison to discuss the theories of living in a reality influenced by race. Organized by civil rights activist Kimberlé Crenshaw and other activists and thinkers, the meeting made great strides in the consideration of race in modern times.

Although the idea of CRT has been around since the early 70s, the workshop was the first instance where a deep discussion was held on the matter. Inspired by previous movements such as critical legal studies, CRT sheds new light on the handling of court cases.

“What (those in attendance) realized was that, a lot of the time, decisions that people were trying to justify under precedent, don’t actually match up with the precedent,” Colwell, “They seem to be serving a different functional role in society, specifically serving certain social interests.”

Those at the conference took this realization and applied it to outcomes in legal cases in the American court system. This allowed them to look at the practice of law through clear lenses rather than filtered through the appearance of race and societal interests.

Court cases such as Terry v. Ohio (1968), which set a precedent on the Fourth Amendment and stop-and-frisk laws, were now being considered on how these previous rulings influenced future legal procedures. Stop-and-frisk laws were passed in New York on stopping people who appear to have suspicious intent and did not coincide with the precedent and instead were manipulated by racial profiling.

“As you can probably tell, that specific legal tradition isn’t really what people mean when conservatives talk about critical race theory,” Colwell said.

This story was written by Connor Baldwin. He can be reached at [email protected].