Renzo Silvera plays chess, but not with pawns. For Silvera, a senior in the College of Engineering, money management in college feels just like that game of strategy.

“You gotta see who your opponent is,” Silvera says. “In this case, it’s the financial system. And then, instead of just looking one ahead, try to look five or more steps ahead.”

Silvera speaks from experience, and lists off books from self-made millionaires with ease: When he was ten years old, his family moved from his home country of Peru to San Jose, California, which neighbors the entrepreneurial Silicon Valley. Not long after that, his parents introduced to him the concept of personal money management.

“They just kinda let me do it on my own,” Silvera says. “Since the age of 17, I have not asked them for anything.”

So when it came to college, Silvera knew the numbers game. Thanks to outside, private scholarships, institutional grants and savings from a side hustle, he says he was able to avoid taking on student loan debt. In his sophomore and junior year, he became a Resident Assistant, and saved money that way, too.

“That’s a big advantage, for sure. Instead of paying loans, I can use that for investments that can be profitable,” Silvera says.

But for many other students, going up against the financial system alone is frightening, and budgeting for bills can be a mind-boggling process. In addition to accumulating high amounts of debt, managing money from day-to-day remains the most formidable challenge, with nearly half (47%) of college students saying they don’t feel prepared to do so, according to a 2019 survey by EVERFI, an organization focusing on social inequity within America’s education system.

“It’s a hard game,” Silvera says. “It’s very complicated.”

Pass Go and Collect Loans

The EVERFI report, titled “Money Matters on Campus,” also found that while six in 10 students have taken or intend to take out loans to cover their tuition bills, only 65% plan to pay those off in time or in full.

These trends are cause for concern among some professors at Marquette University, one of whom shared her own struggles while in school.

“When I was in college, my dinner was microwave popcorn with parmesan cheese,” Lora Reinholz, instructor of finance and Marquette alum, says. “I was so broke, in my last semester I went part-time because it was cheaper than full-time.”

Reinholz took out thousands in student loans, recalls finding grocery stores on campus too expensive, and in the both the 1980s and 2021, she says students are asking themselves the same questions: “‘How am I going to pay back my student loans in addition to my renters insurance, my transportation, my food? Am I ever going to get new clothes, or hang out with my friends, or travel to see my parents?”

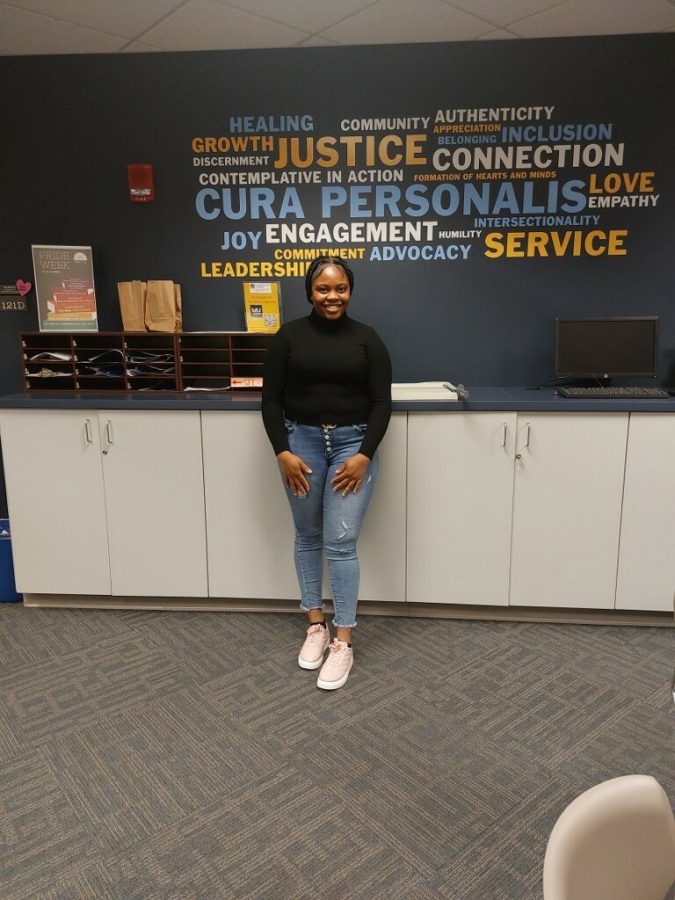

When Taylor Morant, a senior in the College of Communication, arrived on campus as a first-generation student who commuted, she was asking herself some of those questions — especially about covering her tuition bills. Because her mother had turned to student loans to finance her high school education, it was an option Morant herself took, she says.

“I don’t know if there will be a time when I stop paying back college loans,” Morant says. “I’ve taken out a loan every single year so far.”

According to the Pew Research Center: “About two-thirds (65%) of first-generation college graduates owe at least $25,000 or more, compared with 57% of second-generation college graduates.”

But whether they’re first-generation status or not, students of varied economic backgrounds feel unprepared to responsibly handle student loans, Reinholz says.

“There are some students walking around with well over $100,000 in debt, which is really scary,” she says.

Over the past decade, student loan debt has increased by 107%, according to an analysis of Federal Reserve numbers by CNBC News. Today, close to 44 million Americans have accumulated nearly $1.7 trillion in student debt, with the average total of student loan debt at $30,000, per U.S. News data.

Draw Two: Financial Health and Emotional Health

Stress levels increase among students when it comes to managing money, because financial health and emotional health are so closely connected, Reinholz says. And according to the 2019 financial survey by EVERFI, the three highest points of stress are the following: fear of tuition rising, having enough money to last the semester and landing a job after graduation.

There was no Marquette tuition increase for 2021-2022, as rates are set by the Board of Trustees after considering certain costs. According to the school website, 46% of tuition dollars are used for faculty and staff compensation, 27% is used for student scholarships and 16% is used for student support. The other 11% goes toward facility and administrative services.

So with no fear of tuition rising, the two highest points of stress are having enough money to last the semester and landing a job after graduation, Morant says.

“I have savings, but it goes down quickly. There’s always something that goes wrong,” Morant says.

Like her car breaking down, for example.

So she can have enough money to last the semester, Morant commutes to campus and works two part-time jobs while at Marquette. And although auto repairs are a necessary expense, surprises like that eat away at her pocketbook savings.

And because of her two part-time jobs, Morant feels as though she can’t afford to take on an unpaid internship, even though it could benefit her career: College graduates who have had internships are 90% more likely to receive job offers than graduates who didn’t, according to an analysis of survey data from the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) by WIRED.

“I’m not sure if I’m going to get a journalism job,” Morant says.

But Morant is not alone. For Vanessa Morales, a junior in the College of Arts & Sciences who is also a first-generation student, these points of stress can distract from college classes. She says she feels as though she has had to choose between going to class and clocking in “a lot of times,” because she needs to make money.

This is a concern for professors like Reinholz, who says that if students in the classroom are stressed out because they are working too much, their main focus is not necessarily on learning the material.

“The job is helping you pay for things, but you really do need to focus on school,” Reinholz says.

But as Morant and Morales say, focusing on school is tough. For them, it’s a game of balancing risk and reward.

Risk and Reward

But even with student debt and stress levels climbing high, evidence documents that having at least a bachelor’s pays off in the long run, because adults who have completed college tend to accumulate more wealth, according to Forbes.

Ian Gonzalez, vice president for finance at Marquette, echoes that sentiment.

“You may be taking out loans in order to pay for that degree, or you may be working extra jobs,” Gonzalez says. “Obviously, there’s pain to get to a point like that, but I can tell you that the payoff in the end is high.”

While Reinholz echoes this sentiment, she says that pain can impact students’ ability to stay engaged in their professional life, which in turn impacts productivity and future pay.

In other words, she says, if the risk becomes more than the reward, it is important to ask for help.

“We want the best for our kids,” Reinholz says. “If you don’t tell anybody, no one is going to know. And if no one knows, how can we help?”