Following the issuance of a Marquette University hearing for two student conduct violations, Brooke McArdle, a senior in the College of Arts & Sciences, is preparing to mount a legal defense.

“Several lawyers in the community have reached out to me, and I plan on having legal counsel at the hearing,” McArdle said. “If (Marquette) does give me any sort of violation, I will sue.”

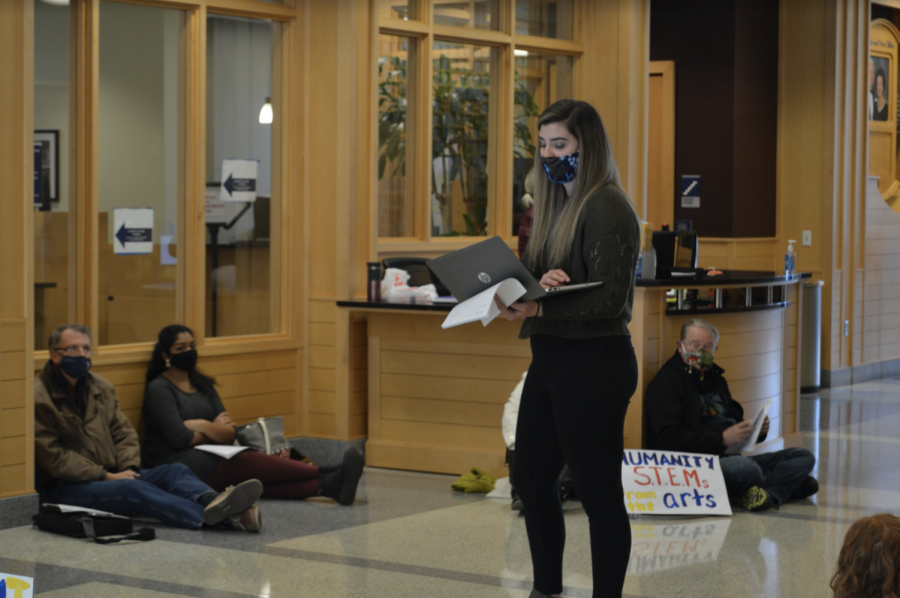

An email arrived in McArdle’s inbox ten days after she helped organize and lead a sit-in demonstration at Zilber Hall, which was aimed to show student support for the hundreds of Marquette faculty and staff at risk of losing their jobs.

The separate student conduct charges read: “Refusing to show or surrender a university identification upon request by a university employee acting in the performance of his/her duties,” and “Violating published policies and rules governing residence halls, student organizations or the university.”

The citation and subsequent hearing exemplify a coercive approach from the Marquette administration to suppress the collective undergraduate voice, McArdle argued. Because no other student present at the sit-in was sanctioned, McArdle said she felt intentionally singled out.

“I was the one at the sit-in that handed out the financial records of Marquette … it’s clear they are intimidated that an undergraduate can get their hands on that,” McArdle asserted, adding: “Marquette has proven time and time again that they do not support dissent on campus. While President Lovell claims to value student perspective, he is clearly turning a blind eye when a student is sanctioned unequally for using her voice.”

University spokesperson Chris Stolarski said in an email that he cannot comment on a pending student conduct case.

No students provided their name or university identifications because administrators did not clearly identify the source of that policy, or what the ramifications could be if students declined, McArdle said. Nevertheless, four times throughout the six-hour sit-in, McArdle said university administrators demanded the participating undergraduate students surrender their IDs.

“They did not present students with all the information necessary for students to be able to make an informed decision in the matter,” McArdle said.

McArdle said she did, however, offer her name to the dean of students, Stephanie Quade.

“There should be no reason why I am charged with surrendering my identification, because (Quade) knew who I was,” McArdle said. “I gave up my identity, without needing to give up my identification.”

Citing the Student Conduct Handbook and university demonstration policy, administrators from the Office of the President and the Office of the Provost periodically asked students to leave. Administrators also warned they would call the Marquette University Police Department to force unidentified participants from the premises. Students refused to leave, and MUPD was not called.

Participants in the sit-in were additionally instructed to follow two rules: do not block entrances or business proceedings within the building, and maintain a social distance to abide COVID-19 safety guidelines. Students honored those requests, McArdle said.

Under updated university demonstration guidelines, students, staff and faculty members who wish to demonstrate on campus must receive permission to organize at certain spaces. While public spaces — the Alumni Memorial Union, its adjacent green space, the Central Mall and other public property — are open for demonstrations, according to the university demonstration policy, student organizers must receive prior written approval from Quade to use other campus spaces.

“I didn’t contact Stephanie Quade prior to the demonstration, because the demonstration policy does not apply to Zilber,” McArdle said, referencing an established precedent of demonstrations at Zilber Hall.

Revisions to the demonstration guidelines came after months of faculty and student pushback against policy that left advocates for free speech and union organizers deeply concerned, Brittany Pladek, assistant professor of English, said.

“It was revised primarily as a form of union-busting wielded against the Marquette Academic Workers’ Union, the grad and (non-tenure track) union at Marquette,” Pladek said in an email. “The policy remains an affront to free speech on campus.”

The sit-in concluded with no other complications, McArdle said. Yet, a little over a week later, McArdle woke up on a Saturday morning to dual student conduct violations. Because she was notified on the weekend, McArdle said she was given little time to gather witnesses and attain legal counsel.

“Saturday and Sunday are not business days. No university administration member is required to answer emails on those days. Consequently, I had to wait 48 hours to hear a response from anybody,” McArdle said. “It’s very clear Marquette … will do as they see fit with regards to timeline (and) properly notifying students of conduct violations.”

McArdle and Pladek both noted that the enforcement of student demonstration policy appears to be inconsistent and based in the optics of publicity.

“The demonstration and identification policies Brooke allegedly violated are not things MU’s upper administration actually cares about,” Pladek wrote in an email. “They’re enforced unevenly, to punish the voices, like Brooke’s, that MU’s upper administrators can’t spin into good press.”

Earlier in the fall semester, Marquette’s Black Student Union held a demonstration at Zilber Hall, urging administrators to uphold their purported commitment to diversity initiatives. Weeks later, Marquette’s Native American Student Association also held a demonstration that concluded at Zilber Hall, calling upon the institution to alter its seal and to respect the existence of its indigenous students. None of the students involved in either demonstration have yet to receive student conduct citations.

President Lovell announced concessions to BSU in a Marquette Today newsletter. By choosing to use phrases such as “work with,” Pladek argued the university inappropriately characterized its involvement as collaborative rather than compelled.

“The administration took credit for its students’ hard work; it spun its own recalcitrance into publicity for itself,” Pladek said in an email.

But Pladek said the administration cannot put a positive spin on the potential layoffs and ensuing demonstrations.

“It is hard to make good press out of firing hundreds of people during a global pandemic because you refuse to listen to your own faculty’s proposed budget alternatives,” Pladek said in an email. “To me, this is a very clear case in which a student organizer was punished by Marquette for doing exactly the kind of brave, difficult, world-changing work Marquette always claims to value — for Being the Difference.”

Jonathon Jimenez, a senior in the College of Education, said McArdle was targeted intentionally.

“It is inhumane, unprofessional, unethical and immoral,” he said. “She is speaking her mind, protecting not only the students of Marquette, but also staff and faculty. She is fighting for everyone here.”

McArdle’s hearing is scheduled for Nov. 5 at 11AM.

“We have fallen so, so far from the Jesuit values we hold dear,” McArdle said. “The Marquette administration is solely responsible for that demise.”

This story was written by Lelah Byron. She can be reached at lelah.byron@marquette.edu.