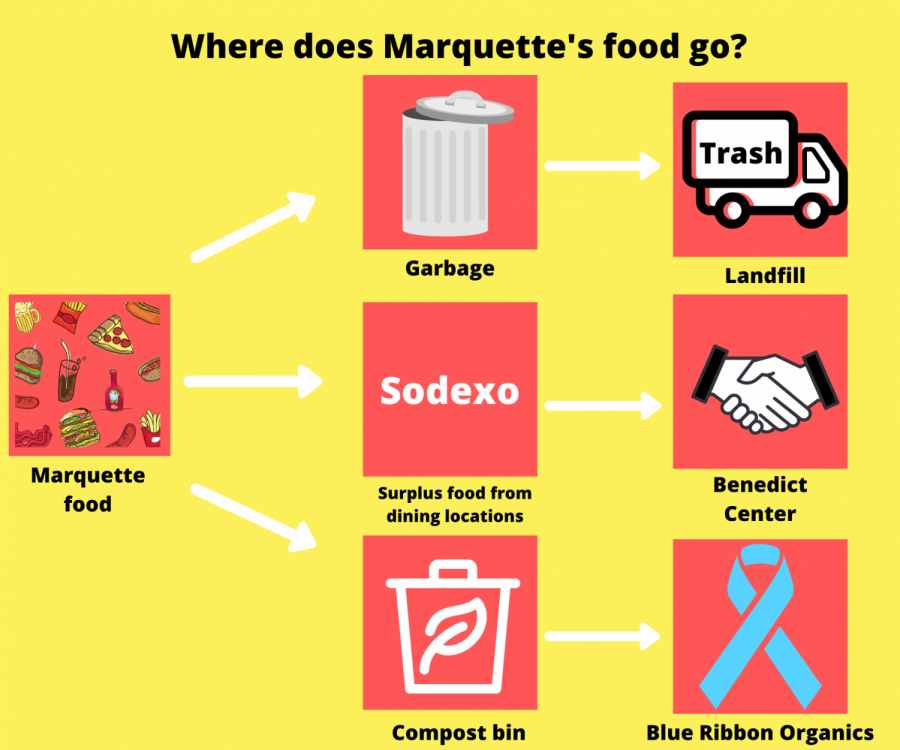

Each day across campus, food waste finds its way into trash cans and compost bins, along with empty drinks, napkins, and papers. While dropping food into these bins may seem simple, it is far from the final step of Marquette’s food waste journey.

Unused, uneaten or spoiled food finds its way home in one of three places: the landfill, in gardens or on plates at the Benedict Center.

The destination that students are perhaps the most familiar with is the landfill. Once food finds its way into trash cans on campus, it gets picked up and taken to Emerald Park Landfill in Muskego, Wisconsin, along with the rest of Marquette’s waste.

Landfills, however, provide a suboptimal environment for food breakdown. Greenhouse gases such as methane and carbon dioxide get released by waste, displacing oxygen. With a lack of oxygen, food breaks down slowly and releases large amount of methane. This contributes to 18% of methane emissions from U.S. landfills, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Sodexo at Marquette diverts food waste by composting across campus, said Melanie Vianes, director of operations, retail and catering for Sodexo at Marquette, reducing Marquette’s contribution to food waste in landfills. She said Marquette has been composting for six years, but their relationship with current composting partner Compost Crusader began nearly three years ago. Compost Crusader is a Milwaukee-based compost service that collects food and organic waste from residential and commercial customers.

The program at Marquette began with Straz Dining Hall, but has grown to include seven locations around campus.

Compost Crusader works with other Milwaukee schools including University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee. Marquette composted a little more than half as much food and organic waste as UW-Milwaukee, which has four locations across its campus. Since May, Marquette has composted 24,805 pounds while UW-Milwaukee has composted 45,643 pounds according to data collected by Compost Crusaders.

Overall, Marquette’s compost pick-ups since May have been less successful than UW-Milwaukee’s, Compost Crusaders’ data showed. Both schools had 29 scheduled pick-up dates; across all locations, Marquette had 131 individual bin visits while UW-Milwaukee had 99. Of Marquette’s individual bin visits, only 51.9% were successful with four contaminated bins, 50 empty or missing bins, and nine services cancelled. As for UW-Milwaukee, visits were successful 77.78% of the time with one contaminated bin and 21 empty bins.

Pick-up services may be cancelled when production is low, such as over the summer or Thanksgiving break, Vianes said. In some cases, locations with particularly low use, such as compost placed in the School of Dentistry, will be brought to one of the seven locations on campus for pick-up, rather than adding another one.

Additionally, Vianes said the partnership is in a time of transition as compost regulations are changing. Items such as the single-use silverware that could be found in places like the Brew are no longer accepted, nor are the new Starbucks cups. She said this has affected the level to which Marquette is able to compost and the accuracy of food waste numbers, in addition to other food management system changes.

Vianes said as composting efforts re-stabilize, Sodexo is adjusting targets and is working to be on the forefront of sustainability.

“It’s a global campus and everyone has to take part in the program. And that’s the way it would work best,” Vianes said.

It is the responsibility of both the university to educate students about composting and of the students to make an honest effort to ensure Marquette’s program can reach its full potential, Vianes said.

Grace Wagner, Compost Crusader operations director, said education is vital when it comes to composting effectively.

“It takes five seconds to do it correctly, but it also takes five seconds to mess it up,” she said. “It’s just the forming of new habits. If there’s no education to back (the introduction of compost) it just ends up becoming an extra landfill bin.”

When compost is picked up, Wagner said, it is searched for contaminants – any non-compostable items. If the number of contaminants is small, they are picked out. However, if there are too many to properly de-contaminate the bin, it will be taken to the landfill.

“Composting is not only for the planet and for cost benefits to road projects or growing your own food, it also creates community, which is really exciting,” Wagner said. “People get excited about diverting their waste, they talk to their neighbors about it.”

Once the compost is picked up by Compost Crusader, it is taken to Blue Ribbon Organics, a family-owned and operated company in Caledonia, Wisconsin. In addition to Compost Crusader, Blue Ribbon Organics also works with institutions such as Milwaukee County Zoo, Outpost Natural Foods and the Victory Garden Initiative to produce compost for gardens as well as mulch.

Blue Ribbon Organics is the only company that accepts post-consumer compost materials in Southeast Milwaukee, Wagner said. Pre-consumer material is any food that does not reach consumers, such as surplus food or food remnants.

Accepting post-consumer materials increases the risk of contamination because the responsibility to compost correctly is put on a greater number of people, Wagner said. It is more likely that people will be unaware of how to compost or mistake the bin for a trash can, which discourages many from accepting post-consumer material, she said.

At Blue Ribbon Organics, the food gets turned into compost for various kinds of gardens to help new plants and food to grow, allowing for natural nutrient cycling and minimizing the impact of food waste on the environment.

But not all of Marquette’s unused food ends up in compost bins or trash cans. Some of the surplus food from dining halls, campus events or the Simply-to-Go refrigerators gets repurposed in Sodexo’s food recovery program.

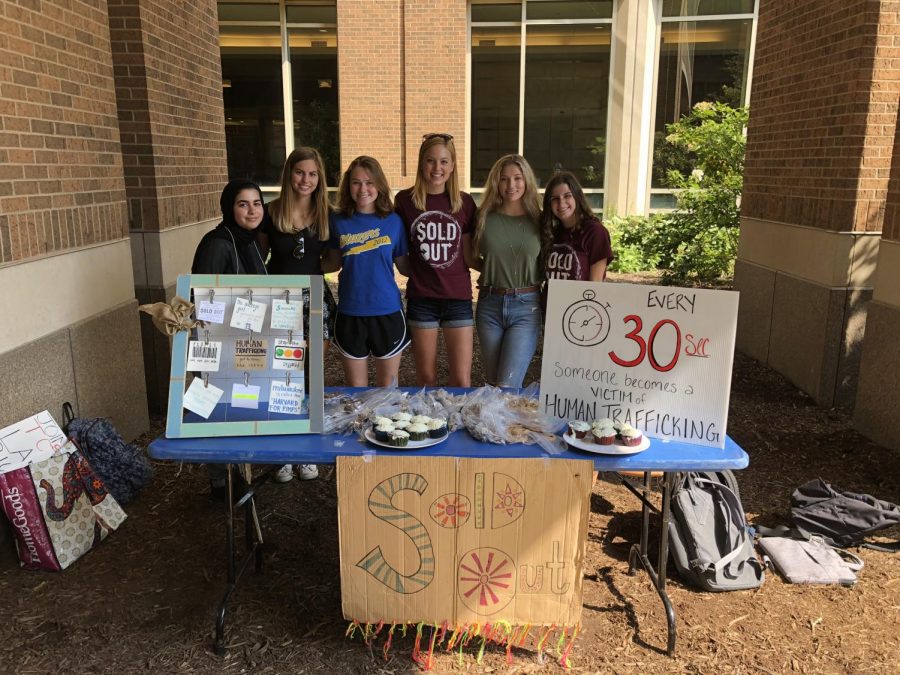

In 2004, Marquette began working with Campus Kitchens to use surplus food to create meals for those around Milwaukee. Campus Kitchens is a national organization that works with universities to create food recovery programs and make meals for the community. Nearly two years ago, however, the company downsized and its partnership with Marquette ended.

This fall, Marquette implemented its own food recovery organization: Marquette University Neighborhood Kitchen. Christine Little, kitchen coordinator, joined Marquette in September. She said she hopes to grow MU Neighborhood Kitchen to the size that Campus Kitchens was.

“Re-establishing the relationships we had in the past is really important, keeping that good will, we definitely don’t want to lose that,” she said, adding that food recovery is not just about diverting food from landfills, but also about improving food security.

As MU Neighborhood Kitchen re-strengthens Marquette’s food recovery efforts, it is focusing on one partnership with the Benedict Center.

The Benedict Center provides substance abuse and mental health treatment, education and support for women who are in any phase of the justice system: incarceration, pre- and post- trial. It provides a variety of programming and classes to create a safe place for women to navigate the justice system, as well as their own life and community.

MU Neighborhood Kitchen’s first food recovery took place the week of Nov. 11. One hundred salads were collected from campus and deconstructed to freeze toppings that will later be used in soups, casseroles, desserts and sides, Little said in an email.

Along with the recovered food, Sharon Hope, MU Neighborhood Kitchen chef, used Stuff the Truck donations to cook enough meals for 20-30 women at the Benedict Center. Hope has been with the program since partnering with Campus Kitchens and is a Sodexo employee at Straz Dining Hall.

The women who are a part of the Benedict Center often don’t get adequate access to meals, making partnerships such as that with MU Neighborhood Kitchen important, Janet Miller, Women’s Harm Reduction Program assistant, said. For these women it is more than food. She said sitting down to share a meal allows for socialization, creating a network of support and community.

“Our women are always looking for supportive resources. A lot isn’t going their way … Knowing that Marquette is providing meals is life-affirming,” Miller said.

The food and subsequent feeling of community is a large contributor to the recovery process, said Miller, adding that the partnership with MU Neighborhood Kitchen entwines with the Benedict Center’s mission to provide a supportive community for the women in order to treat them with dignity and respect.

Miller said she looks forward to re-strengthening the relationship between the Benedict Center and Marquette’s food recovery program. Little said MU Neighborhood Kitchen will provide one meal a week, but aims to work toward four meals a week.

While composting and programs like MU Neighborhood Kitchen help to reduce food waste retroactively, reducing waste at the front end is vital. Source reduction is the number one preferred approach to minimizing food waste, followed by feeding hungry people, feeding animals, industrial uses, composting and landfill/incineration, according to the EPA’s Food Recovery Hierarchy.

The EPA suggests a number of strategies for reducing food waste at universities in the categories of purchasing, serving and engaging with students. Some tips include performing food waste audits, reducing batch sizes, going tray-less, buying local foods and educating students on how and why they should reduce food waste.

Marquette dining services has switched to tray-less dining to discourage students from taking more food than they are likely to eat, Alex Abendschein, marketing manager, said. He said campus dining is also moving toward compostable containers and Simply-to-Go packaging, which is a gradual process as old products get used and new materials are transitioned in.

As for food purchasing, Sodexo partners with a variety of vendors, including Sysco, Midwest Foods and Prairie Farms. Of these vendors, 39% are considered local sources, stationed within 250 miles of campus.

“As a company, our impact, our sustainability impact, is important to us. We need to be looking at ways that we can choose food products, or incorporate food products, that have less of an impact and leave a smaller footprint behind,” Abendschein said.

This story was written by Amanda Parrish. She can be reached at amanda.parrish@marquette.edu.