While Marquette’s former warrior mascot was replaced in 1994, a controversy over Native American representation continues to exist in another university trademark: the seal.

The seal was first implemented in the early 1900s. The image of Father Marquette is based off a William Lamprecht painting titled “Pere Marquette and the Indians.” The artwork depicts a “romantic vision of reciprocity and dialogue among members of the Illini and Miami tribes and Father Marquette,” according to the university’s website. The painting shows Fr. Marquette and a group of Native Americans deliberating a direction to move toward overlooking the Mississippi River.

However, the seal does not contain the entire image of the painting, which changes the meaning, said Lynne Shumow, curator for academic engagement at the Haggerty Museum of Art.

“The controversy is the way in which it’s cropped, (which) totally alters the narrative,” Shumow said. “It looks like Father Marquette is the one saying, ‘This is where you go,’ so it really changes this whole power structure.”

A historical record also suggested that the seal depicted a less than reciprocal relationship.

“The lower half represents Father Marquette pointing to the Mississippi river which he discovered. Numen Flumenque means ‘God and the River’ — indicating that Marquette made known the Deity to the Indians and the Mississippi to the White Man,” according to a Marquette University News Bureau statement found in the Department of Special Collections and University Archives.

Emilia Layden, curator of collections and exhibitions at the Haggerty Museum of Art, said while she believes there was no intentional malice, the cropping of the image does erase some of the “nuance and complexity” of the original.

The cropping highlights a larger conversation of cultural appropriation among Native Americans.

The Cambridge Dictionary defines cultural appropriation as “the act of taking or using things from a culture that is not your own, especially without showing that you understand or respect this culture.”

“We have different nations across the Americas, and they are very diverse,” Mark Powless, manager at Southeastern Oneida Tribal Services in Milwaukee and member of the Oneida Tribe, said. “So to slap some kind of image on a helmet or a jersey and say that that’s ‘Indian,’ for one, is just completely irresponsible and inaccurate.”

In May 2019, Maine became the first state to pass an act barring the use of Native American mascots in public schools. Maine Gov. Janet Mills said in a statement that she signed the bill into effect after hearing from local Native American communities how those mascots were a “source of pain and anguish.” Rep. Benjamin Collings of Portland, Maine, said he was “grateful” Mills passed the act, as Native Americans “are people, not mascots.”

Powless said mascots create false perceptions of cultural meanings.

“If you spoke to an individual who was not educated in what a chief is, they would probably provide a very stereotypical answer,” Powless said. “Each tribe has a different understanding of what a chief is. Within our tribe, the word that we have basically translates to being a good man.”

Powless said while indigenous peoples are prone to appropriation by mascots, this is not always the case for other racial or ethnic groups.

“Americans would never do this with any other race. There’s the baseball team the Cleveland Indians. … (If the team) said, ‘We’re going to change it to the Cleveland Blacks,’ that would be completely unacceptable.” Powless said. “There would be a huge outroar … and everybody would understand how inappropriate that is — or most people would.”

Beyond misrepresentation, there are other consequential social issues facing Native Americans.

A study by the National Center for Health Statistics observed suicide rates for ethnic groups from 1999 to 2017. They found that the suicide rate for Native American or Alaska Native females in the United States increased by 139%, the highest of any racial or ethnic group, according to a study by the National Center for Health Statistics. For males of the same ethnicity, the suicide rate increased by 71%. The average rate increase for females and males of all ethnicities together in the United States amounted to 53% and 26%, respectively.

Powless said that although one definitive reason cannot be named for the trend, it is likely related to historical trauma.

“Attempted ethnic cleansing and genocide sort of ripped the soul and fire out of our people,” Powless said. “This was delivered to us over and over and over again in painful ways over the course of centuries.”

More than four in five Native American and Alaska Native women will encounter violence in their lifetimes, and these women are 1.7 times more likely to be physically injured than non-Hispanic white women, according to the National Congress of American Indians. NCAI also reported 56.1% of Native American women experience sexual violence, with 96% of survivors experiencing this violence at least once at the hands of a non-Native American perpetrator.

Samantha Majhor, an assistant professor of English at Marquette with a focus in Native American literature and member of the Yankton Dakota and Assiniboine tribes, said that along with other factors, such as the gap between jurisdiction of federal, state and tribal law enforcement agencies, sexualization of Native American women in the media is one of the contributing factors to this violence.

“Especially in Disney, we get that sort of romanticization of John Smith and Pocahontas,” Majhor said. “Part of that portrayal is of the Native woman as available.”

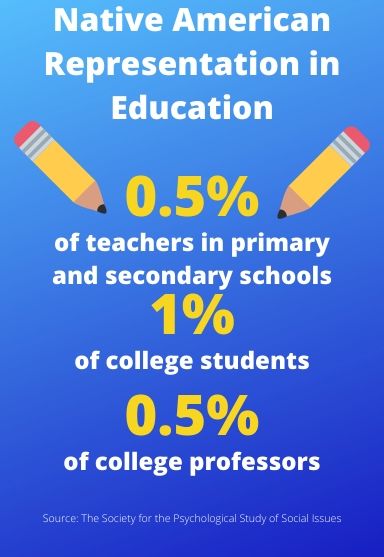

Representation of Native Americans in the media of primetime television and popular movies ranges from zero to 0.4% of characters, with less than 1% of children’s cartoon characters and 0.09% of video game characters being Native American, according to a 2015 study by the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues. Most of these characters depict indigenous peoples as historical 18th or 19th century figures.

Majhor said contemporary representation of Native Americans in the media often isn’t done by Native Americans themselves.

“In today’s portrayals, we have a lot more Native media speaking back, but again, it is difficult for Native people to get a seat at the table,” Majhor said. “Even before contact, there was this imaginary ‘other,’ this imaginary ‘Indian,’ and that became the label for (all tribes).”

She added that the best thing to do is use the name that each tribe uses for itself when speaking of them.

Majhor said along with a need for distinction between tribes, there is a need to draw a line between authentic and costume jewelry.

“I think buying beautiful artwork from Native people is a fabulous thing to do. I wouldn’t consider that appropriation,” Majhor said. “I think wearing a fake headdress on Halloween is very much appropriation.”

Before the contemporary representations of Native Americans came to be, boarding schools attempted to strip Native Americans of their cultures.

Thousands of Native Americans attended federal boarding schools from the 1890s to 1980s, according to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. At these schools, administrators and teachers punished Native Americans for speaking their indigenous languages or wearing any traditional clothing. The schools were also a site of physical, sexual and spiritual abuse.

Powless said his family has a personal connection to this era of boarding schools: his great-grandfather was enrolled.

Powless said his great-grandfather did not talk much about the experience likely because of all the pain it caused, but the effects were still evident.

“(My great-grandfather’s) mother died while he was at boarding school,” Powless said. “His family tried to contact him to inform him … and the school was not giving my great-grandfather those letters, but because there were students who were coming from the reservation, he was hearing from them. So he was never informed that his mother died — he was not allowed to attend her funeral.”

Powless said the schools also contributed toward many Native Americans inflicting self-harm.

“(Survivors) started drinking as a coping mechanism because of the pain they experienced,” he said. “They also had been taught not to love themselves because of their language, their culture, their identity. They were pretty much told that (their culture) was of no value and that they had to adopt American values.”

The effects of the boarding schools still linger today, Powless said.

“When I was a child, all of the elders in my community spoke the language,” Powless said. “Now, out of a population of about 17,000 tribal members, we have about five that speak (the Oneida language) fluently.”

The misrepresentation of Native Americans in the classroom today contributes to the myth that Native Americans no longer exist, Majhor said.

“But it’s all really wrapped up into one ball of not fully understanding that Native people are still here,” Majhor said. “And there’s a whole lot of history — intertwined history — that when we don’t understand the full complexity of it, we continue to perpetuate some of these deeper problems.”

Powless said the repeated suppression of culture continues to affect the way Native Americans feel internally.

“What you’re looking at is a population of survivors, but also a population that has really been demoralized,” Powless said. “If you have no self-worth, no self-value and you don’t have any values or any of those beautiful things to really cling to in your being, in your culture, it really leaves an individual empty.”

Powless said one way for society to move toward a more accurate representation of Native Americans is through the education system.

“A lot of schools and colleges use Native mascots, and these are institutions of education,” Powless said. “Native history is not taught in schools, and Native history is American history.”