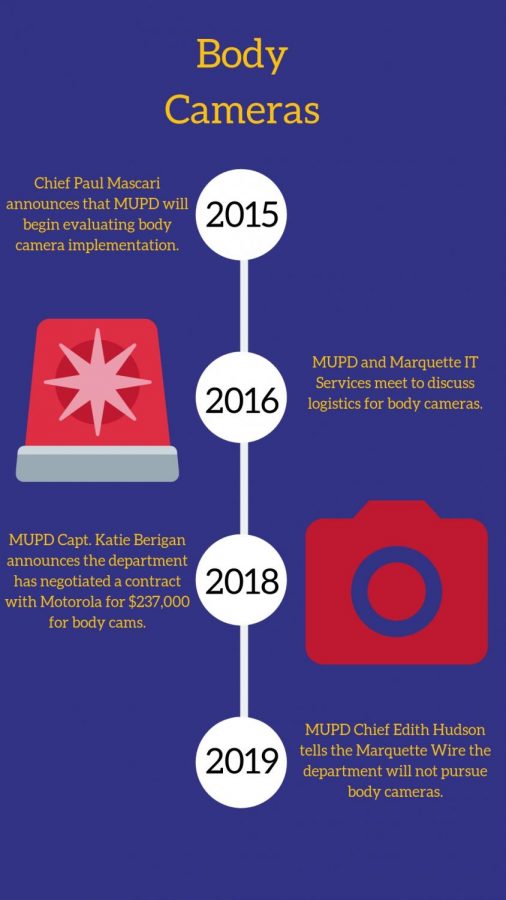

The Marquette University Police Department has decided to remain without body cameras, police chief Edith Hudson said.

MUPD has debated implementing body cameras since 2015, according to previous reporting by the Marquette Wire.

Hudson said the cost of storing body camera footage contributes to MUPD’s decision not to implement the cameras.

She said this cost is exacerbated by the fact that open records laws have caught up with body camera technology and require longer video file retention periods.

However, such laws are not currently in place. In 2017, Assembly Bill 351 was proposed in the Wisconsin legislature. The bill would’ve created rules relating to video retention periods for police departments using body cameras, requiring body camera footage to be stored for a minimum of 120 days. According to the Wisconsin Legislature’s website, on March 28, 2018 the Senate didn’t agree on the bill, and it hasn’t passed.

MUPD’s years-long process started in December 2015 when the department’s previous police chief Paul Mascari said an MUPD initiative was checking into the purchase and use of body cameras, according to MUPD Advisory Board minutes.

MUPD followed up on this initiative the next month. In January 2016, Mascari told the Wire that MUPD planned on meeting with Marquette IT Services to comb through logistical elements of implementing body cameras.

The purpose of MUPD’s meeting with ITS was to evaluate costs of different models of body cameras and storage of body camera footage.

Three weeks after the meeting, the MUPD Advisory Board unanimously endorsed body cameras, according to previous reporting by the Wire. The Advisory Board offers counsel to university officials about MUPD policy and initiatives.

The following semester, MUPD told the Advisory Board that it had tested three different models of body cameras and decided on body camera provider Axon’s body-worn model, according to the Advisory Board minutes.

“The plan is for body cameras to be worn by shift commanders and those officers actively on patrol,” the meeting minutes said.

One year after this meeting, Mascari “indicated that MUPD is not where it had hoped we to be (sic) at this point with respect to the implementation of body cameras,” according to the Advisory Board minutes.

The process slowed down due to a price change of the Axon body cameras, according to the board minutes.

The minutes said Axon originally offered to provide body cameras for a free year-long trial. The Wire previously reported that Axon’s National Free Trial Offer would provide interested U.S. police stations with one camera per officer.

The Advisory Board minutes said that Axon’s offer was more popular than Axon anticipated, and the company no longer offered free equipment.

However, when the Wire reached out to Axon in December 2017, a representative said the offer was ongoing.

Then, in March 2018, Capt. Katie Berigan told the MUPD Advisory Board that MUPD had chosen Motorola Solutions as its body camera vendor, according to previous reporting by the Wire. MUPD negotiated a $237,000 contract with Motorola. The funding would need to be approved by the Board of Trustees, and the contract would require that unlimited storage and equipment be replaced every 30 months.

MUPD submitted the request for funding to the Board of Trustees the following month, according to previous reporting by the Wire.

The Marquette Wire recently reached out to Jordyn Leadingham, a spokesperson at Motorola, for more information on MUPD’s contract with the company. Leadingham said in an email she had limited access to account information.

Hudson wasn’t at MUPD when the trial periods occurred, but she said officers’ opinions about the body cameras wouldn’t have been a “deciding factor” on whether to implement them.

“It always helps if they like them, but it wasn’t an option,” Hudson said, referring to the fact that equipment isn’t optional for officers. For instance, officers can’t opt out of carrying pepper spray.

Since MUPD participated in body camera trial periods, Hudson said studies have come out “that contradicted early manufacturer-sponsored research regarding the impacts and efficacy of body cameras.”

One study that found contradictory results regarding the effectiveness of body cameras was conducted by The Lab @ D.C. in 2016. The organization is a research group under the administration of D.C. mayor Muriel Bowser.

In the study, 2,224 members of the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department worked with The Lab @ D.C. to examine body cameras. The study compared a “control” group — members of D.C. MPD who didn’t wear body cameras — and a “treatment” group — members of D.C. MPD who were assigned body cameras.

Over the course of 11 months, the study tracked the use of force by police officers and civilians, civilian complaints and arrests for disorderly conduct. The D.C. Lab concluded that there was no significant difference between the two groups in these categories.

A study conducted by the nonprofit research organization CNA had different results from The Lab @ D.C.’s study. CNA’s 2017 study followed more than 400 officers at Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department. Two hundred and eighteen officers were equipped with body-worn cameras, 198 were not and all 400 officers were monitored for 20 months.

The study found that the number of citizen complaints for officers who wore body-worn cameras decreased by 16.5 percent. Contrastingly, the number of citizen complaints for officers who didn’t wear body cameras decreased by 2.5 percent.

In addition to decreasing citizen complaints, CNA concluded that the group of officers who wore body cameras also saved time and money that would’ve been spent investigating those complaints. According to the study, a detective might spend 80 paid hours investigating a complaint against an officer without a body camera, whereas the same detective might spend six hours investigating a complaint against an officer with a body camera. The study said officers with body cameras saved the LVMPD $6,222 in investigating time.

While CNA’s study indicated that body cameras saved LVMPD money, one of the reasons MUPD is foregoing implementing body cameras is because body cameras would cost too much.

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Police Department decided to go the opposite direction. It purchased Axon body cameras in July 2017, said UWMPD police chief Joseph LeMire. Lemire’s department purchased the unlimited cloud-based storage program from Axon at the same time it purchased the physical cameras.

LeMire said the initial cost of the physical cameras was $38,736 for his department. For each year after, the cost is $40,896 per year. This includes the storage cost for body camera footage as well as maintenance, LeMire said.

LeMire said he is unable to quantify exactly how much time the body cameras save, but he said the impact of the cameras is noticeable to members of UWMPD. The cameras are both a record of civilian interactions and a training resource for officers, he said. Officers spend “less time investigating because (they) have the video that shows you exactly what happened,” LeMire said.

Similar to athletes watching post-game tape, officers are able to review interactions and learn from them.

“I think (body cameras are) very important for being transparent,” Meghan Stroshine, an associate professor of criminology at Marquette, said. “For saying, ‘Look, we have nothing to hide. We’ll have our officers wear these and then you can see what they see when they encounter someone who is suspicious or resistant or what have you.'”

During MUPD’s body camera initiative, Mascari told the Wire MUPD was looking into privacy policy issues concerning when body cameras should be on or off.

Privacy is a significant component in the body camera debate. It impacts both police officers and civilians. While body cameras can be perceived to create transparency, they can also be viewed as an invasion.

“(Police officers will) say, ‘I don’t want to have a camera on me while I’m eating lunch, or I’m on the phone with my wife, or I’m going to the bathroom,’” Stroshine said.

This is also an issue for civilians, who might not want to be recorded by officers when they are in sensitive or compromising states.

The initial public reaction to UWMPD implementing body cameras was positive, LeMire said. Now, two years out, LeMire said the cameras are a non-issue and don’t get much attention at all.

LeMire acknowledged that departments across the country are going the opposite route, especially smaller departments that do not have large budgets.

“People are starting to either not go with body cams or getting rid of them strictly because of the cost,” LeMire said.

He said departments have to make decisions such as choosing between buying a squad car, hiring an officer or implementing body cameras.

In September 2018, the Madison Common Council’s Finance Committee allocated $108,000 to fund a year-long body camera pilot program for the Madison Police Department. The program never came to fruition because in November 2018, the funding was voted down and revoked by the committee, according to the Madison Common Council livestream of the meeting.

“In the limited amount of time that America has had body cameras, studies have not borne out that it has any impact on officer behavior whatsoever,” Madison Alderwoman Amanda Hall said. “We have here a situation where we’re starting to see that this isn’t protecting officers, this isn’t really protecting citizens, but we’re spending money on it and moreover putting our faith in it to do both of those things.”

For MUPD, Hudson said the department is prioritizing continuing existing community outreach programs and also adding new ones.

One program MUPD is continuing is safety training classes for students and faculty. During the classes, officers teach participants physical maneuvers to protect themselves, as well as what to do in an active shooter situation.

MUPD is also continuing the Adopt a Residence Hall program, in which two police officers are assigned to each residence hall. The program was announced in October 2017 in the minutes from an MUPD Advisory Board meeting. The minutes said the residents have the opportunity to get to know the officers specific to their hall and may be more likely to reach out to them.

Participating officers volunteer for the positions. Hudson said these programs aim to create consistency in MUPD’s relationship with students.

Hudson also mentioned the Diversity Liaison program, through which officers attend events like Pride Prom in a non-MUPD capacity.

“(Diversity Liaison officers) provide an extra ear for students who are of different ethnic backgrounds, so they can meet with someone they identify with,” Hudson said.

Capt. Ruth Peterson said there are currently seven officers participating in the Diversity Liaison program.

“I think we had more officers volunteer than we had positions available,” Peterson said.

Hudson said MUPD is also looking to add a feature to MUPD’s Eagle Eye app that will allow students to call a LIMO, similar to ride-share apps Lyft and Uber.