Vehicles driving off-road into a building is not an uncommon scene. With a variety of causes including intoxication, pedal error or operator error, more than 21,000 incidents of vehicle-to-building crashes have been documented since 2013, according to the Storefront Safety Council. The problem is not unfamiliar to Marquette University.

Three vehicle-to-building crashes on Marquette’s campus included two crashes into the Al McGuire Center and one into Johnston Hall.

The first crash into the front entrance of the Al McGuire Center on 12th Street occurred Oct. 17, 2017. A medical incident in which the driver blacked out caused the driver to lose control and crash into the entrance.

The second crash into the entrance of the Al McGuire Center Nov. 24, 2018, was a result of the driver’s intoxication. The driver hit the 12th Street entrance after losing control of the vehicle.

The third crash May 15, 2018, into the front of Johnston Hall on Wisconsin Avenue occurred when a Milwaukee County bus driver took a turn onto Wisconsin Avenue too fast and lost control.

A vehicle also crashed near the Wells Street side of the Alumni Memorial Union around 2:30 a.m. Saturday morning, and it appeared to have turned on its side. It is currently unclear if the vehicle hit the Alumni Memorial Union.

The vehicle-to-building crashes could be attributed to the high level of traffic on an urban campus, MUPD Capt. Jeff Kranz said. It is an anomaly, he said, that three crashes occurred at the same intersection in such a short period of time.

Kranz added he doesn’t think there are any characteristics of the Wisconsin Avenue and 12th Street intersection — near where the three confirmed vehicle-to-building crashes occurred — that could be the cause of the high frequency of crashes.

He said that particular intersection isn’t the most challenging one on campus. Kranz said the intersection of Wisconsin Avenue and 11th Street has a high volume of crashes, though he said he does not see a specific cause for the high volume. The 16th Street corridor is also a difficult traffic area due to the high number of vehicles passing through, he said.

“There is nothing environmentally that I can see that would have caused (those crashes) at that (12th and Wisconsin) intersection,” Kranz said. “We looked for that consistent cause and all three had a different cause to the loss of control.”

Kranz said he doesn’t think traffic flow at the intersection played a role in the crashes. MUPD looked at crashes on campus after the incidents, but it did not find a spike in crashes in or near that intersection.

Marquette is not the only Milwaukee college campus to experience vehicle-to-building crashes.

A car crashed into a sign outside of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Student Union located on East Kenwood Boulevard Feb. 17, 2018, according to a TMJ4 article. Police were chasing the car — stolen by three robbery suspects — when the driver lost control and hit the sign. The suspects were unaffiliated with UW-Milwaukee.

Several days later, Feb. 21, a woman unaffiliated with UW-Milwaukee crashed into the west wall of the Student Union parking structure, near the building’s entrance. The driver pressed the accelerator instead of the brake as she turned into a parking spot, according to a UW-Milwaukee Police Department incident report. The UW-Milwaukee director of external relations did not respond to questions about potential causes for the crashes.

While Milwaukee School of Engineering has not experienced vehicles crashing into major buildings, the institution has had several instances of vehicles hitting parking structure pillars. Since the Viets Field and Parking Complex located on N Broadway opened in August 2013, one car has hit a pillar in the parking structure and several others have hit a pole near the exit, Billy Fyfe, director of public safety at MSOE, said.

A Milwaukee County Transit System bus crashed into Johnston Hall in May 2018.

In partnership with the Texas Traffic Institute at Texas A&M, Storefront Safety Council, a private group of volunteers dedicated to ending vehicle-to-building crashes, has been collecting and analyzing such incidents involving commercial and public buildings as well as transit stops, public areas and non-residential structures since 2013. Storefront Safety Council pulls data from court and fire department records, media and anecdotal reports and published studies. Crashes are analyzed for cause, building type and age of driver.

Storefront Safety Council has more than 21,000 documented crashes, 12,000 of which have been analyzed. About 250 to 300 incidents get added to its database, accessible by request, each month, Rob Reiter, co-founder of Storefront Safety Council, said.

The council’s data has been cited in the Federal Register, the official journal of the United States’ federal government. Data was cited in Denial of Motor Vehicle Defect Petition, a notice by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration regarding a Ford recall. Its data has also been featured in an ABC News broadcast.

Reiter said storefront and related crashes tend to occur more frequently in large cities with large college populations.

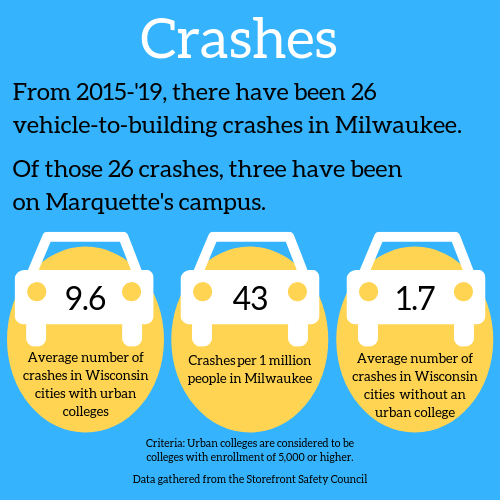

On average, Wisconsin urban college campus cities experienced a total of 9.6 crashes per city between 2015-’19, while non-college campus urban cities in Wisconsin averaged 1.7 total crashes per city between 2015-’19. Cities were categorized as urban if they were major cities or large urban areas. They were categorized as college campus cities if they contained a college with an enrollment of 5,000 or more students.

In comparison to nearby states — Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota and to Pennsylvania — Wisconsin’s averages fall in the middle. The average number of crashes in urban college campus cities ranges from 3.9 crashes per city in Minnesota to 11.4 crashes per city in Indiana. The range of the average number of crashes in urban non-college cities is 1.3 crashes per city in Minnesota to 3 crashes per city in Pennsylvania.

Milwaukee, specifically, has had a total of 26 vehicle-to-building crashes between 2015-’19. This equates to 43 crashes per 1,000,000 people. Of the 26 vehicle-to-building crashes occurring over the past four years in Milwaukee, Marquette’s campus has been the site of three of these crashes in the past two years, a relatively high number for an area concentrated around one intersection.

Reiter said he thinks the frequency of vehicle-to-building crashes are higher on urban campuses than non-urban campuses because students are driving on and off campus to activities. He said the young age of students and the party culture of college can contribute to drinking, driving irresponsibly and losing control when speeding, which are factors that play a big role in vehicle-to-building crashes.

Storefront Safety Council’s data shows that 20 percent of vehicle-to-building crashes involve drivers ages 20 to 29, a larger percentage than any other age group. Drinking related causes account for 18 percent of vehicle-to-building crashes. Other vehicle-to-building causes include operator error, pedal error, traffic accident, medical and ram-raids and burglaries in which heavy vehicles are driven through the windows or doors of a closed business.

“What it boils down to is young people doing what they shouldn’t be doing,” Reiter said.

The drivers involved in the 2017 and 2018 crashes into the Al McGuire Center and 2018 crash into Johnston Hall were aged 38, 36 and 59, respectively. Thirteen percent of vehicle-to-building crashes involve drivers ages 30 to 39, and 8 percent involve drivers ages 50-59.

Reiter said campuses have lower speed limits and should thus have lower rates of vehicle-to-building crashes.

As for vehicle-to-building crash prevention, Reiter said it is difficult because the causes lie within driver behavior.

“No one has been able to change driver behavior,” Reiter said. “But you can prevent injury by keeping people away from cars.”

He said the focus of those concerned with vehicle safety has been on changing laws surrounding behaviors like drinking and driving, and now cell phone use. Reiter added that seat belts were created to protect people because driver behavior couldn’t be changed.

One common approach to vehicle-to-building prevention is the implementation of barriers and bollards, which are posts to prevent vehicles from entering specific spaces. Blockaides, a safety company, educates customers about the role of barriers and bollards.

Natalie Wackeen, manager at Blockaides, said the company first works with customers to look at the site and identify any specific issues involving crashes. Next, it recommends which bollard would work best depending on site characteristics such as speed limit and types of vehicles common to the site.

Wackeen said customers often have already worked with an engineer and architect and contact Blockaides to find the best solution.

“Bollards are a great fit most of the time, but there might need to be a combination (of bollards and barriers),” Wackeen said, and added that bollards don’t always fit the aesthetic, and underground obstacles may need to be worked around.

Blockaides, Wackeen said, has worked with several universities including Elizabeth City State University in North Carolina and State University of New York College of Medicine. She said Blockaides worked most recently with contractors at Broward College in Florida to make recommendations and help with approval, and bollards are now being installed.

In emails regarding the crashes into the Al McGuire Center and Johnston Hall obtained from open records requests to MUPD, plans for bollards in front of the Al McGuire center were discussed between MUPD and Facilities Planning and Management, with concerns over the effectiveness of bollards. In an email sent by Paul Mascari, former MUPD police chief, he questioned the necessity of bollards, calling the first Al McGuire Center incident a freak accident.

“What happened there could happen at any of our buildings. Happy to discuss further,” the email read.

In response, Joel Smullen, project manager of facilities planning and management, sent an email that said he contacted Jens Construction and was provided an estimate of $9,500 to install bollards.

When contacted about the estimates, Smullen said in an email, the Department of Facilities Planning and Management has not received costs for putting in bollards, adding that there is no proof that bollards would have been effective in any of the three crashes as their causes were driver related rather than issues with the safety of the roadway.

American Society for Testing and Materials International, a nonprofit volunteer organization that develops standards for product testing, created the Test Method for Vehicle Crash Testing of Perimeter Barriers, also titled ASTM F3016/F3016M – 14. Joe Hugo, a manager at ASTM International, said it is an improvement upon previous bollard standards.

“We saw a great need for this standard,” Hugo said. “A lot of previous standards for bollards didn’t work.”

Standards set the regulation for testing procedures and regulations. Like other standards, Hugo said, ASTM F3016/F3016M – 14 helps anyone interested in a product determine which is best for them by providing a regulation for testing that helps determine if a certain product would be an effective choice.

Hugo said the ASTM F3016/F3016M – 14 standard is designed to simulate a 5,000-pound passenger Sudan crashing into a bollard at 30 mph.

Hugo said bollards can be implemented in different kinds of barriers, adding that depending on the location of the of the bollards, there are multiple look options such as concrete walls or planters. Hugo said options like planters could offer a more decorative option for a college campus.

“(Bollards) are pretty much the solution to all of these (vehicle-to-building) incidents,” Hugo said.

Reiter said barriers — including bollards, walls, masonry, fences, large lawn areas and trees — offer crash resistance. When deciding which kind of barrier to use, Reiter said it depends on the kind of threat and structure.

Reiter said because the crashes into the Al McGuire Center have been passenger vehicles at street speeds and involved a level of incapacitation, creating a low wall where pedestrians cross through the intersections could be helpful. He said additional approaches could include bollards, which would offer space to move through the barrier, or benches for a more visually appealing option.

Reiter said increased police patrol could help mitigate vehicle-to-building crashes to an extent by helping to reduce speeds. Lower speeds reduce the severity of a crash, but the risk of crashes associated with deliberate attacks or medical emergencies will not be reduced if a physical barrier isn’t implemented.

The logistics of installing barriers is not always easy, Reiter said. Barriers are anchored in concrete and if there are sewers or waterways under the surface, they may need to be rerouted or worked around.

Additionally, if installed on city streets, barriers must comply with building codes, Reiter said.

Alderman Robert Bauman, representative of District 4, said if an organization were to request the installment of barriers or bollards on city property, the organization would need to be granted a special privilege through public works.

If Marquette were to request barriers or bollards on its campus, it would first have to apply to the City of Milwaukee Department of Public Works with a plan for construction, Bauman said. Next, engineers would look at the plan with Marquette and its contractors until an agreement is reached. The plan would then be approved through DPW and the Common Council. He said this process generally takes a matter of months.

“(In Milwaukee), barriers are generally planters because they are technically moveable,” Bauman said. “There are a lot in the city, but they are mostly for decoration.”

Bauman said the installation of bollards is more complicated and potentially more expensive because, unlike the planters, bollards need to be dug into the ground. Breaking ground risks running into underground utilities and infrastructure.

As for the cost of preventative measures, Reiter said projects generally range from $5,000 to $10,000. Reiter said he suggests looking at the long-term effects of installing barriers when weighing the cost.

While someone can never know what the price of a prevented crash would have been, Reiter said, if it is a reoccurring problem one can compare the cost of repairs from previous crashes to the cost of installment.

He added it is beneficial to have protection in areas where crowds form during events or busy times.

“You can look at the cost of risk factors like glass buildings, but there is not a price on the cost of life,” Reiter said.

On Marquette’s campus, Kranz said MUPD has increased its presence at the 12th Street and Wisconsin Avenue intersection. He said patrol cars are making more frequent passes through the intersection.

“We hope the presence of police cars will cause drivers to reduce their speed to reduce damage when there are crashes,” Kranz said.

When on patrol, MUPD looks to make sure cars are obeying traffic rules, stopping at traffic lights and for pedestrians, Kranz said. He added that speeding is an issue officers look out for on 16th Street as well.

Kranz said MUPD also has police cars at the Al McGuire Center when there are events that increase crowds and traffic.

However, finding a solution to crashes with similar results but different causes is difficult, Kranz said.

It is hard to avoid vehicle-to-building crashes, he said, without putting up cement barriers and making the campus feel closed. While you don’t want to sacrifice safety for appearance, Kranz said, using barriers seems excessive.

In emails obtained from MUPD, concerns about pedestrian, student and staff safety were expressed by departments including the Office of Public Affairs, athletics and the Office of the President. Marquette officials have been making efforts to organize meetings between Marquette departments as well as with Bauman and DPW.

An email sent by Rana Altenburg, vice president for public affairs, in response to an email regarding pedestrian and vehicular safety at several locations including both 12th Street and Wisconsin Avenue read, “Please let me know how best to convene this dialogue to determine actions steps. We have reached out to Alderman Bauman as well who shares out concerns. Our facilities and MUPD teams stand ready to participate as well.”

A meeting was set to take place December 2018. It is unclear whether this meeting occurred.

Altenburg said in an email measures have been made to improve vehicular and pedestrian safety on Marquette’s campus. Some of these measures included increased installation of signage, medians, signal lights, plantings and barriers in front of the Al McGuire Center, she said.

These efforts, however, were not in response to the two crashes into the Al McGuire Center and the crash into Johnston Hall, Altenburg said in an email. Rather, they were a part of general campus safety measures.

“The three incidents … happened because drivers did not follow traffic laws or in one incident, due to a medical emergency — they were not related to the safety of the roadway,” Altenburg said in an email. “As such, no new physical measures were taken on 12th Street.”

Altenburg said in an email the organizations involved in conversations about preventative measures have included Facilities and Planning Management, MUPD, Marquette University Student Government, Student Affairs and the Office of Public Affairs, Bauman and DPW. Marquette continuously evaluates vehicular and pedestrian safety on campus, she said.

“It’s a matter of my staff being out there and enforcing speeding violations and reckless driving,” Kranz said. “We try to be present. Our focus is on traffic infractions that put safety in jeopardy … and are causing a threat to campus.”