“Is today real? Is today happening?”

When Mac Fowler gave himself his first shot of testosterone, he said he felt lightheaded with joy. He couldn’t stop smiling all the way back to the clinic waiting room where his dad sat enraptured by a level of “Angry Birds.”

“All I could think about was, holy s—, I’ve waited for five years and this is finally starting,” Fowler, a junior in University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s College of Education, said.

Fowler is now 11 months into testosterone injections, sporting a beard and speaking in a low register. He recalled the start of his transition excitedly, pausing often to pet his therapy dog Huggy.

But for Fowler and many other people who are transgender, the process to medically transition is long, complicated and can be rife with discrimination.

Angelique Harris, associate professor of sociology and the director for the Center of Gender and Sexuality Studies at Marquette, said for some health care professionals, it is difficult to understand the concept of identifying outside of one’s sex assigned at birth. As a result, there are regimented obstacles transgender people must maneuver in order to come close to medically transitioning. The process to become approved for hormone replacement therapy can take at least a year, often longer.

On the checklist: months of mental health counseling, preliminary clinic appointments, blood work, doctor approval and reviewing payment options.

“We have this whole idea of ‘you gotta be sure, you gotta be sure,’ and that’s one of the reasons the process is so long,” Harris said.

Fowler coordinated his transition with two doctors—one being his parents’ physician and the other a doctor recommended by fellow LGBTQ friends.

“It was a little tricky, because I’m not good at communication myself,” Fowler said.

Once someone who is trans looks to surgically transition, however, an especially formidable problem arises: negotiating with insurance companies. Coverage for transition procedures, including top or bottom surgery — surgery on the chest or genitals as part of gender reassignment — can be a challenge to receive. Although providers can cover mental counseling and hormone replacement therapy, some feel disinclined to foot hefty surgical bills.

“They have on your insurance policy a list of the types of surgeries you can have. Cosmetic surgery is what it’s considered for a top surgery or a bottom surgery, not a medical need,” Jody Dwyer, a public relations and marketing manager for tech company Ubimax and freelance writer on trans issues, said.

Dwyer’s name has been changed at her request to protect her identity.

Fowler and supporters of the trans community find issue with this classification, arguing insurance companies misunderstand the severity of dysphoria or mental health problems accompanied with not feeling comfortable in one’s body.

“For me, dysphoria is looking in a mirror and not recognizing the person looking back,” Fowler said.

Although testosterone has greatly improved his confidence, he said he still has bad days. Top surgery would greatly alleviate remaining stress. With most insurance providers unwilling to pay for such procedures, many trans people turn to unconventional methods to fund their transitions.

“I have had friends … go through GoFundMe to get funding for their surgeries,” Dwyer said.

Both Fowler and Jesse Bursch, a freshman at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design, said they plan on paying out of pocket for surgeries. If his new insurance doesn’t cover his top surgery, Fowler said he has thought about offering art commissions.

Some trans people also experience the sudden shock of switching providers and no longer being eligible for HRT.

“They now get a doctor that doesn’t allow it, and they go through withdrawal and had a lot of pain,” Dwyer said.

The unemployment rate for transgender people is three times the national average, and 27 percent of transgender people who applied for a job in 2017 said they were fired or not hired because of their identities, according to a national survey. With rampant job insecurity, there is a risk that some transgender people will not receive insurance at all.

“When you consider that the majority of people in the United States get insurance through their employer, that already gives (transgender people) a setback,” said Ann Bagchi, sociologist and assistant professor at the Rutgers University School of Nursing.

For trans people who are uninsured and for trans people with insurance that doesn’t cover certain procedures, out-of-pocket costs can skyrocket. With fees from blood work, checkups and therapy appointments, some trans people are forced into sex work, Harris said.

A 2015 National Transgender Discrimination Survey released by the Red Umbrella Project collected responses from 6,400 transgender adults in America. Among them, 10.8 percent reported experience in sex work. One of the key reasons for participating in the underground industry was a dire financial need.

Merely obtaining insurance does not eliminate all challenges, however.

“People think that if you have insurance coverage, you’re fine, but that’s clearly not the case. If you’re facing stigma and discrimination in a health care setting, then you’re not going to want to go back,” Bagchi said.

Since doctors serve as medical liaisons for patients, finding one who is informed on trans issues is crucial.

“It can be traumatic and emotionally scarring to have a doctor that doesn’t want to explain things to you, that denies your feelings as legitimate or refuses to call you by your preferred pronouns or name,” Dwyer said.

Doctors must acknowledge there are many aspects of health care they take for granted, Bursch said. What may seem mundane and routine to them can be nerve-wracking for people who are transgender.

On paperwork, patients must write down their legal name and gender, forcing some trans people to use their “dead” names, or the names given at birth that do not correspond with their gender identities.

“Even just going to the doctor and sitting in the waiting room and filling out paperwork can be emotionally challenging,” Dwyer said.

Check-ups, too, can incite anxiety.

“There are certain boundaries and feelings of safety that some trans individuals have. For example, if they are a trans male, meaning they were born female, they might not want to have a breast examination … that might make them feel body dysphoric,” Dwyer said.

Additionally, as insurance companies determine which doctors are in a network, dealing with a discriminatory doctor can be common.

“You can legally discriminate against a trans person here (in Milwaukee),” Harris said.

While Medicaid currently covers treatment of gender dysphoria on a case-by-case basis, Wisconsin does not have laws barring gender-transition exclusions from such programs, nor are there laws banning discrimination in health care on the basis of gender identity. Additionally, the Wisconsin Fair Employment Act does not explicitly address discrimination against people who are transgender.

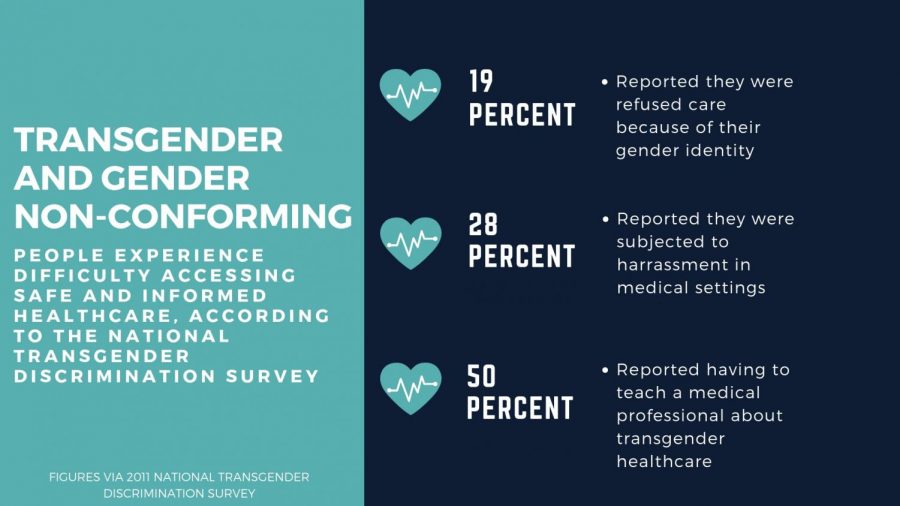

Among the 6,400 respondents of the National Discrimination Survey, 152 were from Wisconsin: Eighteen percent of the Wisconsin sample reported being refused medical care due to gender identity, and 18 percent postponed necessary medical care due to discrimination.

Harris said while some health care professionals have a better understanding of gender, the problem remains with older generations of doctors who have not had inclusivity training or a general awareness of trans people.

“When you’re looking at people who are in health care now, your average 50-year-old cisgender male went to school 20 years earlier and did not learn about these things. … Is he coming into contact with trans people?” Harris said.

Dwyer, who was born intersex and put on estrogen by her parents at age 15, said she is no stranger to discrimination. Many of her doctors were inept at offering support or providing explanations, she said. As an adult, Dwyer approached her OBGYN, who performed her bottom surgery.

“(My OBGYN) didn’t want to talk about it, she refused to answer any of my questions and she just kind of left the room,” Dwyer said.

Bursch, who has not started HRT but said he hopes to within the year, said he has experienced the discomfort of being misgendered.

“I haven’t felt comfortable with doctors for a long time,” Bursch said. Although he recently had a positive experience at the Marquette medical clinic, discrimination back home in Minnesota was common.

“I did get misgendered a lot,” he said.

The Trump administration’s recent proposal to define gender as biological traits identifiable at birth marks a disturbing reversal of acceptance, Harris said.

The proposal would significantly roll back Obama-era legislative policies, including more fluid definitions of gender, protection from medical discrimination under the Affordable Care Act and the federal recognition of 1.4 million transgender Americans. It would also potentially give insurance companies an excuse to refuse HRT or surgical coverage.

“It’s creating a lot of divisions,” Dwyer explained regarding the proposal. “Misunderstandings have been emboldened.”

Fowler said once he heard the news, he closed his laptop and crawled into bed.

“I was like, ‘This is it,’” he said.

Misunderstandings about gender identity can lead to threats of physical and deadly harm against transgender individuals. 2018 has already seen the killings of at least 22 transgender women, according to the Human Rights Campaign. In 2017, advocates reported the murders of at least 29 transgender people, the highest number on record.

For Dwyer and Bursch, starting a conversation with allies remains most important to spread a message of inclusivity and ward against hate.

“Just being willing to listen to their story and just kind of take it in” can be a good first step, Dwyer said.