The evening of President Donald Trump’s inauguration, Maria Bunczak found herself at her first march, right in the middle of an angry, crowded Milwaukee street.

“That might be tear gas or something, but do you see how many old people are here?” her friend shouted over to Bunczak. “Our lungs are young, we’re pushing forward and going to that front.”

When Bunczak, now a sophomore in the College of Nursing, got to the front, she found the gas was a harmless fog, and she kept marching. It’s something she has not stopped doing since.

Bunczak is now the president of Marquette Empowerment, the intersectional feminist club on campus. She’s helped lead protest movements on campus this academic year, like the sit-in against Marquette’s response to a rape case.

She has also participated in two other Milwaukee marches, including the second Women’s March and “March for Our Lives.”

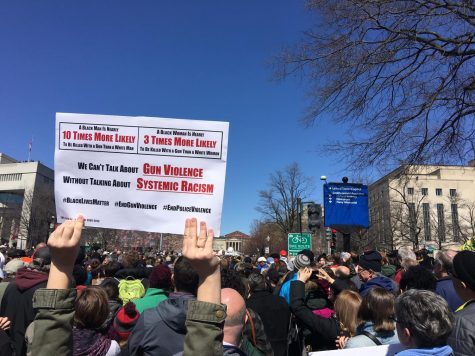

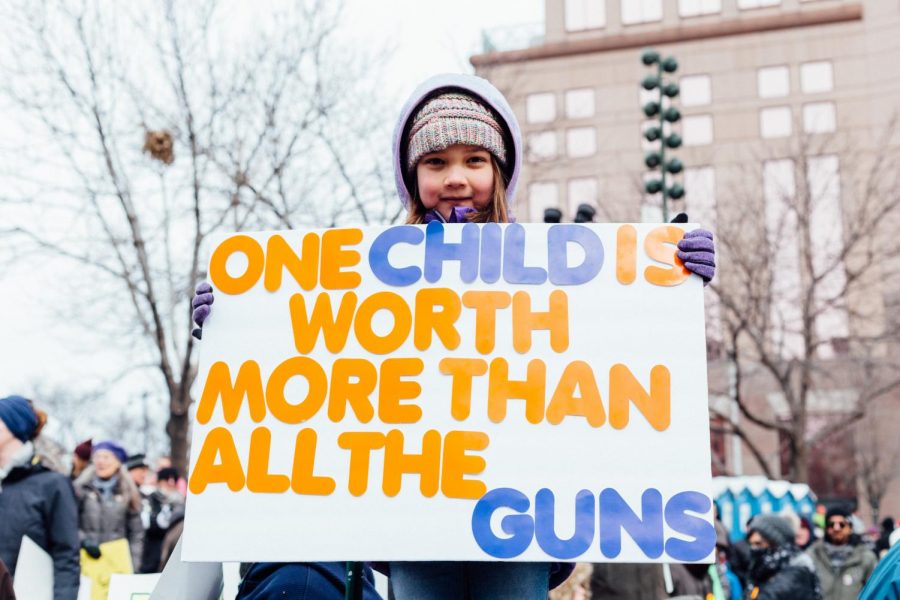

About 800,000 people attended March For Our Lives in Washington, D.C. to advocate for gun control, including some Marquette students.

Marquette students involvement in protests is not new. The university’s protest spirit extends back to the 1960s, at the time of the protests against the Vietnam War.

According to “Milwaukee’s Jesuit University: 1881-1981” by Thomas J. Jablonsky, the role of students was initially undetermined during the mid-1960s.

In 1966, the student government submitted “The Marquette Report: Contributed with positive and mature concern for the present and future progress of our University,” a document criticizing the administration’s statement that student demands should not come before their academic responsibilities.

Then-University President Rev. Raynor formed an ad hoc committee in the fall, eight months after the report was submitted. The committee’s finding were not reported on until two years later. In 1968, the Marquette Tribune published that the new rules would be available the next school year. The guidelines were put in place August 1969.

Katie Blank, a digital records archivist at Marquette’s Special Collections and University Archives, says at the time, the administration was more concerned about student behavior within the classroom, but the national tone quickly found its way to the forefront.

“The university’s dismissal of young men who wore beards or young women who wore slacks in the student union seemed preposterous when crowds marched through the streets in opposition to the war, racism, and poverty,” Jablonsky wrote.

Now, the administration has a little bit of a different view on protests on campus and in Milwaukee. Provost Dan Myers’ main academic field of study focuses on protest.

“I think it’s an important part of our political environment for people to be involved in protest in various ways, and it’s healthy,” Myers says. “The literature in my field shows that countries that have stronger democracies have stronger protest cultures. They go together.”

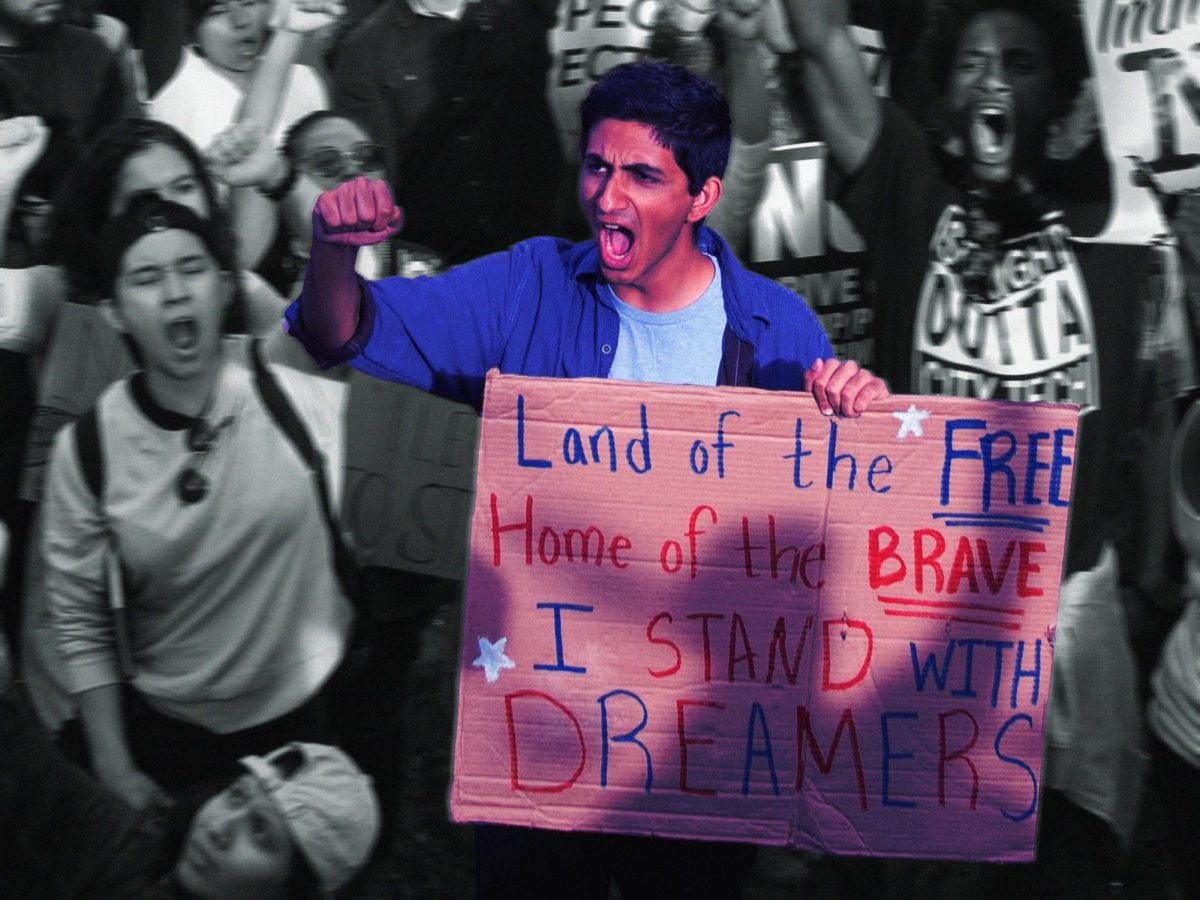

Marquette has joined the conversation, making statements in support of the student population. One statement was in support of DACA students, where they said they’d support Dreamers no matter what.

Milwaukeeans participate in the march to protest the announcement to end DACA.

“Decisions about making statements come down to how (an issue) is impacting our campus community and how it’s impacting our students, our faculty and our staff,” Myers says. “We can’t send out messages about everything that happens in the world, so we try to focus it on ones that are meaningful to people on our campus.”

The demonstrations policy has also changed since the late 1960s. To protest on campus, students have to acquire leadership and prior approval. To maintain safety, groups are responsible to maintain peace, have the presence of university officials and conclude the demonstration.

Students Mary Claire Burkhardt (left) and Nina Gary (right) participate in the march. Photo courtesy of Abby Ng.

Bunczak says she does not feel the statements provide enough support for students, especially those attempting to participate in protests.

“They are saying stuff that makes them look good,” Bunczak says. “They haven’t really said anything really controversial. Even with saying, ‘We will protect Dreamers,’ if they didn’t say that, people would be quitting the school. There would be so much backlash.”

Myers says the level of activism is determined by political groups and the number of protests — including the speakers and events hosted on campus.

Zachary Wierschem, a senior in the College of Business Administration, got involved in protests while participating in the International Marquette Action Program in Ecuador, a program focusing on justice and solidarity.

“The concept that I learned there is righteous anger, and it goes off this idea that, usually, anger has a negative association,” Wierschem says. “But sometimes there’s good anger.”

In the fall, Wierschem attended the Ignatian Family Teach-In, one of the largest social Catholic conferences in the U.S. The conference this year focused on combating racism.

Later, Wierschem joined Marquette students in Washington D.C. in the winter to participate in the March for Life in protest against abortion.

“Usually when people are angry, they want to yell, and with activism and protesting you have a new voice,” he added. “You don’t yell just with your words. You yell with your feet by being where you are. You yell with your presence. You yell with your witness.”

Marquette took a look this semester at the history of protest at Marquette and in the Milwaukee community.

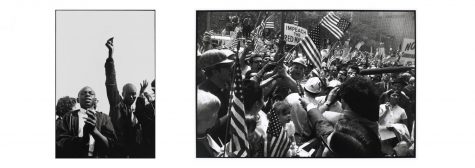

The Haggerty Museum of Art exhibition is “Resistance, Protest, Resilience.” It explores how protest photography from twentieth-century movements, including Civil Rights Movement, Iranian Revolution and the 1984 Democratic National Convention.

On opening night of the exhibit, Mark Speltz, a Wisconsin historian and “North of Dixie” author, sat facing a crowd of over 50 people, commenting on historical protest photos published in Milwaukee newspapers.

He talked about what the violence in the published photographs could symbolize. He drew from the presentation later to discuss how marches in the late 1960s compared to the protests that have occurred over the past academic year.

“I think (Milwaukee’s protests) are similar in that I got a feeling for the scale of the crowd — the perspective for the image gave me a feel for the number of people in the audience or nearby, participating,” Speltz said after scrolling through the Wire’s protest photos.

At “March for Our Lives,” Bunczak said it is important to remember protest in Milwaukee has existed long before Trump’s election.

“Black Lives Matter has been protesting for gun control long before ‘March for Our Lives’,” she says. “We just have to remember that we are now joining them.”

“Black Lives Matter has been protesting for gun control long before ‘March for Our Lives’,” she says. “We just have to remember that we are now joining them.”

Speltz says the protest culture is different because of access to technology, which impacts how movements spread.

“I think there’s much more awareness of issues out there, and I think at the crux of the question of protest and photography and kids and youth today and college students,” Speltz says. “I think one of the main points is the ability to share.”

Ellery Kemner, a sophomore in the College of Business Administration, became interested in political activism after Trump’s inauguration.

Kemner takes photographs aimed at making political statements. She says she sometimes disagrees with her previous work, but considers the change a positive because it symbolizes growth.

“I wish I could say I was really interested in activism before it became a personal issue, but I think that sometimes it hits home for you when everything affects you,” Kemner says. “Being an activist wasn’t just about me — it was about the Milwaukee community and society at large.”

Wierschem says it’s his goal to also have protest be a time for understanding other points of view.

“I find that in some protests where people just don’t listen, it gets to be a battle of power because it’s a battle of who’s the loudest,” Wierschem says. “It’s not actually a conversation where the best idea or best value is portrayed, but it’s the most angry. It’s toxic.”

However, Bunczak says she feels hopeful that students will continue to participate in political activism and protest. At least, Bunczak knows she will.

“The end of a march, I’m usually quite hopeful afterward,” Bunczak says. “Just the fact that I am united with all these other people makes me feel so hopeful. Even if there are people who are against it.”

siddhi sharma • May 29, 2018 at 1:31 am

Hello Alex Groth,

Nice information shared by you and thanks for sharing this useful information with us. “Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Internship to Fellowship Program” The scholarship is Students who have received an associate’s or bachelor’s degree by the time the program commences are encouraged to apply.

Application Deadline is: 31 May 2018

For more information, you can visit the given link:

https://www.developingcareer.com/smithsonian-asian-pacific-american-internship-fellowship-program/

You can also join our Facebook page for the updates. The link is given below

https://www.facebook.com/DevelopingCareer/