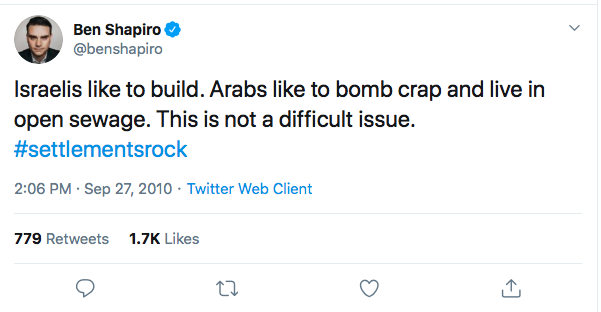

Controversy arose last semester when conservative speaker Ben Shapiro came to campus. Many students were not welcoming toward Shapiro’s lecture series, “Dismantling Safe Spaces: Facts Don’t Care About Your Feelings.” Students and staff planned a protest, but the event continued as planned, was well-attended and went on without disruption.

The same lecture given at the University of Wisconsin-Madison last November did not go as uninhibited. A shouting match erupted between students opposing and students in support of Shapiro’s speech. At one point, protesters blocked the stage and chanted various phrases, stopping the lecture for nearly 10 minutes. Despite these protests, Shapiro still gave his talk and the intended dialogue occurred.

In June, as a response to this protest, Wisconsin Republicans pushed the Campus Free Speech Act through state legislature. It established that disruptions like this could be grounds for expulsion.

The bill says that “a range of disciplinary sanctions for anyone under an institution’s jurisdiction who engages in violent, abusive, indecent, profane, boisterous, obscene, unreasonably loud, or other disorderly conduct that interferes with the free expression of others” will be subject to suspension or expulsion.

This is a dangerous precedent that will inhibit free speech more than protect it.

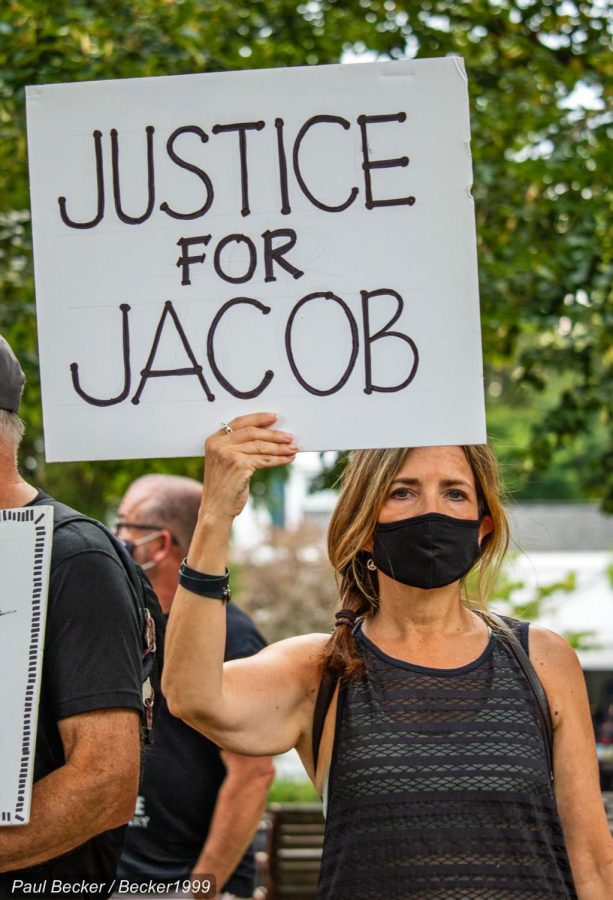

The Madison protest led to no arrests and no physical violence. The protestors even spoke with the campus police department prior to the event to ensure their tactics were lawful. Regardless of the legality of their efforts, these students would technically be subject to expulsion under this new law.

It is sensible for universities to attempt to protect their students from violence. This is not the most recent or most extreme example of campus protests escalating beyond control. But this law could easily be used as a means of intimidation, for both liberal and conservative students.

The point of encouraging dialogue is to educate. It is a difficult task to accomplish if both sides of the discussion are aggressive. That said, universities should be encouraging passionate debate. Kara Bell, the chair of the organization that brought Shapiro to Madison’s campus, said she thought the protest enhanced the event by demonstrating varying opinions.

In defamation law, government officials have absolute privilege from suits during official government proceedings. They cannot be sued for what they say during the meeting and are instead encouraged to speak passionately about their causes. Sometimes passion can lead to crude or hurtful speech, and honesty is crucial in discussing social change. The point is not to allow people to speak aggressively, but to remove potential barriers to fruitful discussion.

Threatening to expel students for protesting events is suppression. At best, the law is over broad and at worst, facially unconstitutional.

Though Marquette is not immediately affected by this legislation, the precedent it sets for campus cultures is chilling. Marquette is a private institution, which means students have zero First Amendment protections from administration. If the university decided to implement a similar rule, it would be within its rights to do so.

It is unlikely that a rule like this would ever be tested at Marquette. The campus has hosted speech for a litany of groups over the last few years, and it would be absurd to anticipate Marquette would start hampering speech now.

As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote in his Letter from Birmingham Jail, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” The consequences of this new law have yet to emerge, but it is sure to have a negative effect on campus speech. If students cannot voice their concerns without the fear of expulsion, then other, potentially dangerous speech is likely to go unchecked.