My grandparents are the kind of in-love that makes people want to believe in soulmates. I lived with them for a while during middle school, and a lot of my nights were spent grinning at the two of them.

With the cassette player whirring in the background, my grandpa would take my grandma by the hand and lead her into a dance across the kitchen tile. Sometimes they would invite me to dance with them, and we’d move ourselves in a triangle back and forth. Other times, I was content to just watch; they were magic, and their happiness was intoxicating from the other end of the small kitchen.

On a recent wave of nostalgia, I decided to go back through my grandpa’s cassette tapes and find their digital equivalents so as to always have them with me in my back pocket. Unfortunately, some of the songs I thought so bright and wonderful as a child didn’t hold up. One of my grandpa’s favorite songs is called “Standing on the Corner.” The titular lyric goes, “Standing on the corner watching all the girls, watching all the girls, watching all the girls go by.”

Even here, hidden in the purest of my childhood memories is the idea of woman as object. While the song played a part in one of my life’s formative experiences, is it the memory or the content of the song that had the largest impact, and does it matter either way if the song is oppressive?

Where else do these subliminal messages lay, and am I a bad feminist for enjoying the music in which they exist?

Music has a dramatic impact on us all. There’s a reason I know all the words to half of Taylor Swift’s discography despite loathing her as a musician. Popular culture, music specifically, is pervasive. While I don’t think content should be censored because I find it offensive, we should pay closer attention to the themes being communicated through the music our society champions.

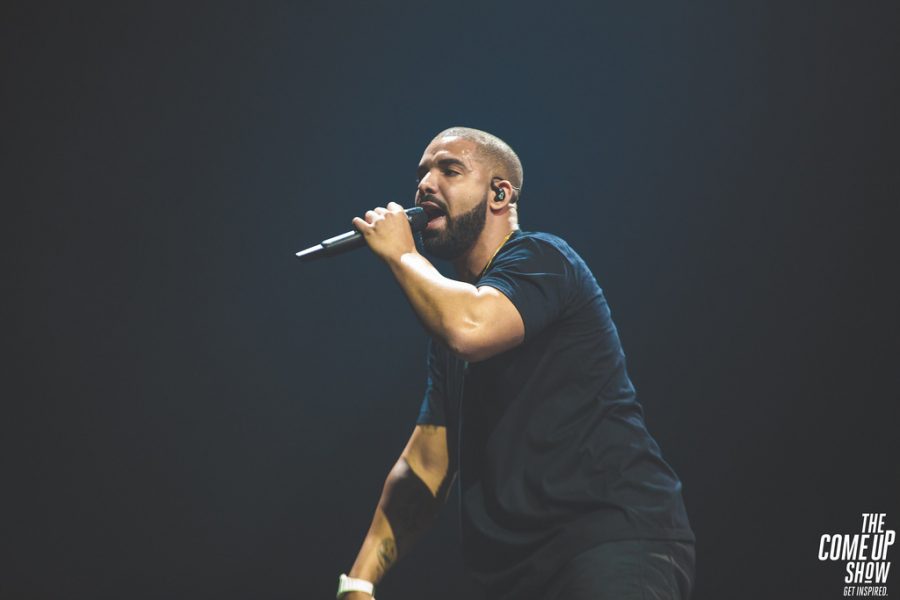

It’s not just music that rewards hyper-masculinity and patriarchal ideals. Casey Affleck, who is facing sexual harassment allegations, recently won an Oscar, despite those allegations. Chris Brown, who physically assaulted Rihanna in 2009, is releasing a documentary about his life and already profiting from an upcoming album. Drake, whom I love but who is notorious for condemning sex-positive women in his lyrics, has faced little to no backlash for his sexist music career.

I think Affleck is a great actor, I really like Brown’s music and Drake is maybe my second favorite celebrity of all time. But aren’t I perpetuating the problem by supporting the work of men who often characterize the very behavior that I claim to combat as a feminist?

There are a lot of things that might qualify me as a “bad feminist,” and though I try to champion equality and fairness, I fail as often as I succeed. If I’m being honest, I’m not going to stop listening to Drake. I haven’t fully reconciled what that means to my moral fiber or my feminist punch card. I know I should be able to provide a more insightful, provoking answer, but in the words of Roxane Gay, “I would rather be a bad feminist than no feminist at all.”