As Election Day nears, the intricacies of what a person’s vote actually means becomes more relevant.

The presidency and the vice presidency are the only elected offices in the nation that are not determined by the popular vote, when each ballot is cast by individual citizens. When Americans vote for the president, they are actually voting for someone else to vote for the president for them.

“It is anti-democratic,” said Michael Donoghue, an associate professor in the history department.

The requirements for the Electoral College are outlined in Article II of the Constitution. Each state has as many electors as it has members of Congress. Anyone can be an elector, though it is usually a prominent politician. The only stipulations on who cannot be an elector are: a sitting member of Congress, federal employe or someone who has committed a rebellious act against the United States.

Most states follow a winner-takes-all rule, which means whichever candidate wins the most votes gets all the electoral votes in the state. Only Maine and Nebraska split their votes, giving one to the party candidate that wins the Congressional race, and the remaining votes to the winner of the popular vote.

The American system is not a “direct democracy” because the people elect representatives to lead and make laws, which has led to some awkward run-ins with the public will.

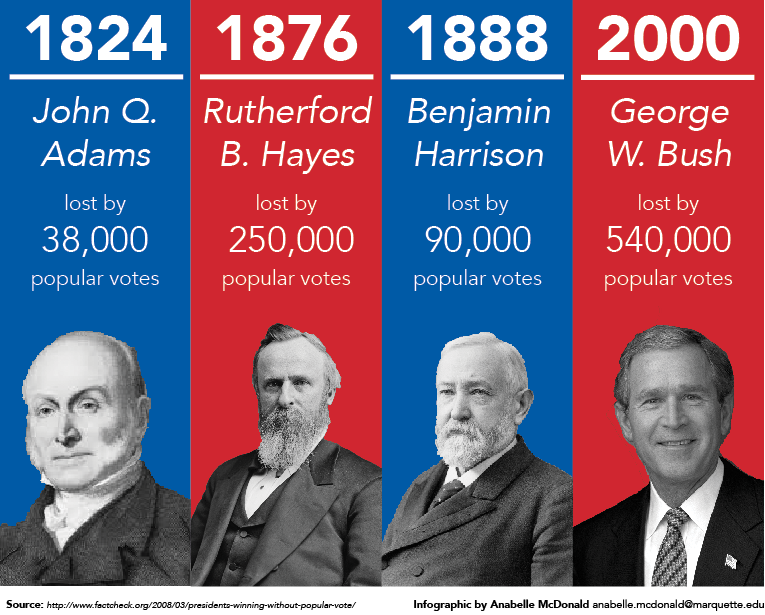

There have been four times in history that the person elected president was not the person who won the popular vote: John Quincy Adams in 1824, Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876, Benjamin Harrison in 1888, and George W. Bush in 2000. Al Gore won that popular vote in 2000 with about 540,000 more votes than Bush.

The system is so contested that there have been more constitutional amendments proposed to change or remove the college than on any other topic (the tally currently hovers around 700). One of these actually took hold – the 12th Amendment which changed the rule that the election’s runner-up would be vice president.

So why have an Electoral College when it could skirt the public will? Simply put, the founding fathers were not about to leave such a big decision up to public will. The system is meant to protect the nation from electing a sweet-talking “demagogue or charlatan,” Donoghue said. Technically, the electors can vote with their conscience, though they are pledged to vote according to their state’s popular decision, and over half of the states have created laws curbing that power. There is no federal law stopping them from voting their mind and no elector has ever been prosecuted from doing so.

“The Electoral College speaks to the skepticism the founding fathers had about direct democracy,” Donoghue said. “They liked the idea of having a bunch of electors who could be appointed in the states – these were often referred to as powerful, the rich and the wise – and they could, in a way, short circuit or subvert the presidential election. The great fear was that a trickster could come along and he could get elected by the popular vote.”

There are many things that have widened enfranchisement over the years, Donoghue said. Letting women and minorities vote as well as the Voting Rights Act of 1965 are among them, but other things set us back, like, arguably, state voter ID laws. Many of the arguments about voter equality come back to the goal of increasing voter turnout.

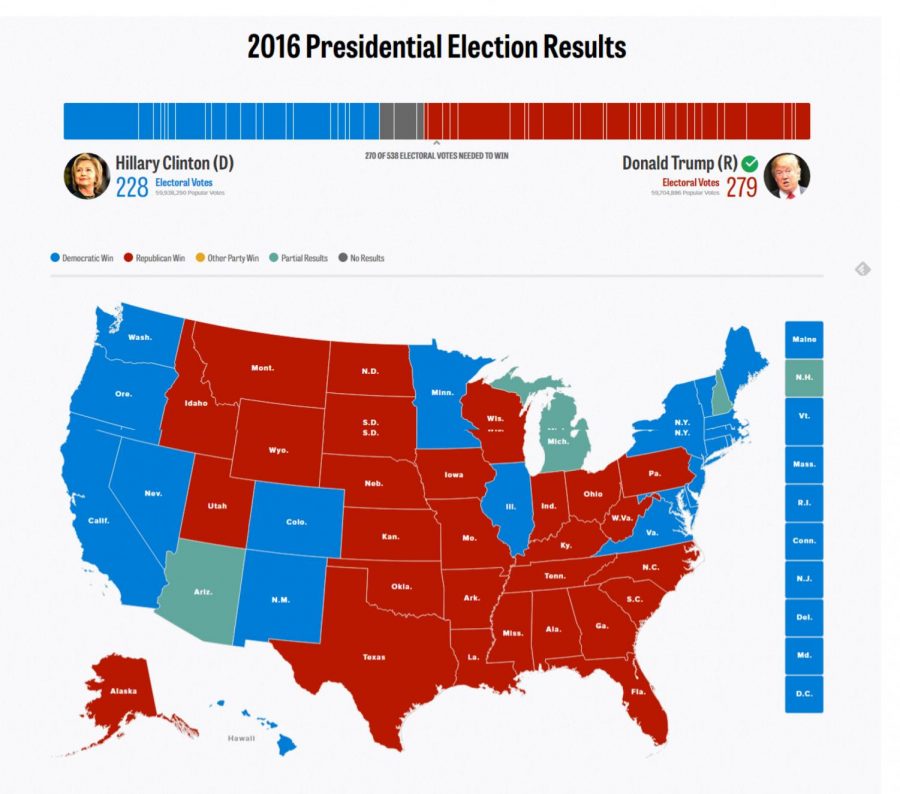

Donoghue said that the system does cause some voters to feel like their vote does not count due to the electoral system. If a constituent is voting in a strongly red or blue state where the popular vote always goes one way, all the electors would vote for the winning candidate – even if they win by one vote.

In a swing state like Wisconsin, the popular vote is ever more variable and can be the difference between the state’s 10 votes going one way or the other. It’s the reason why Donoghue says everyone should be casting their votes.

“Get out and vote, everyone should participate,” said Donoghue. “Especially here in Wisconsin where it counts, and in your home states.”

otto • Oct 11, 2016 at 12:54 pm

A survey of Wisconsin voters showed 71% overall support for a national popular vote for President.

To abolish the Electoral College would need a constitutional amendment, and could be stopped by states with as little as 3% of the U.S. population.

Instead, By 2020, the National Popular Vote bill could guarantee the presidency to the candidate who receives the most popular votes in the country, by changing state winner-take-all laws (not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution, but later enacted by 48 states), without changing anything in the Constitution, using the built-in method that the Constitution provides for states to make changes.

Every vote, everywhere, for every candidate, would be politically relevant and equal in every presidential election.

No more distorting and divisive red and blue state maps of pre-determined outcomes.

The bill would take effect when enacted by states with a majority of the electoral votes—270 of 538.

All of the presidential electors from the enacting states will be supporters of the presidential candidate receiving the most popular votes in all 50 states (and DC)—thereby guaranteeing that candidate with an Electoral College majority.

The bill was approved this year by a unanimous bipartisan House committee vote in both Georgia (16 electoral votes) and Missouri (10).

The bill has passed 34 state legislative chambers in 23 rural, small, medium, large, red, blue, and purple states with 261 electoral votes.

The bill has been enacted by 11 small, medium, and large jurisdictions with 165 electoral votes – 61% of the 270 necessary to go into effect.

NationalPopularVote

otto • Oct 11, 2016 at 12:50 pm

There is no federal law stopping electors from voting their mind because the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld state laws guaranteeing faithful voting by presidential electors (because the states have plenary power over presidential electors).

Now 48 states have winner-take-all state laws for awarding electoral votes, 2 have district winner laws. Neither method is mentioned in the U.S. Constitution.

The electors are and will be dedicated party activist supporters of the winning party’s candidate who meet briefly in mid-December to cast their totally predictable rubberstamped votes in accordance with their pre-announced pledges.

The current system does not provide some kind of check on the public will. There have been 22,991 electoral votes cast since presidential elections became competitive (in 1796), and only 17 have been cast in a deviant way, for someone other than the candidate nominated by the elector’s own political party (one clear faithless elector, 15 grand-standing votes, and one accidental vote). 1796 remains the only instance when the elector might have thought, at the time he voted, that his vote might affect the national outcome.

States have enacted and can enact laws that guarantee the votes of their presidential electors

Instead of being a deliberative body, the Electoral College, in practice, is composed of presidential electors who voted in lockstep to rubberstamp the choices that had been previously made by extra-constitutional bodies (namely, the nominating caucuses of the political parties).

Starting in 1796, political parties began nominating presidential and vice-presidential candidates on a centralized basis and began actively campaigning for their nominees throughout the country. As a result, presidential electors necessarily became rubberstamps for the choices made by the parties. “[W]hether chosen by the legislatures or by popular suffrage on general ticket or in districts, [the presidential electors] were so chosen simply to register the will of the appointing power.”

McPherson v. Blacker. 146 U.S. 1 at 36. 1892.

Presidential electors have been expected to vote for the candidates nominated by their party—that is, “to act, not to think.”

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson summarized the history of presidential electors as follows in the 1952 case of Ray v. Blair:

“No one faithful to our history can deny that the plan originally contemplated, what is implicit in its text, that electors would be free agents, to exercise an independent and nonpartisan judgment as to the men best qualified for the Nation’s highest offices.…

“This arrangement miscarried. Electors, although often personally eminent, independent, and respectable, officially become voluntary party lackeys and intellectual nonentities”