L.J. Cooper, a sophomore in the College of Arts & Sciences, is planning for a dangerous career path: working as a tenured English professor at a university.

Nationally, the number of tenure-track positions is decreasing each year with an increase in contingent faculty, commonly referred to as adjuncts, filling in the gap. Instructors in these positions experience low wages and limited job security.

“I’m aware of the chances (of getting tenure), which are especially grim in the humanities department,” Cooper said in an email. “I’m very concerned about my future, but the intellectual freedom that accompanies an academic career is enticing to me.”

Cooper’s concerns reflect a nationwide movement to improve conditions for adjunct instructors, including recent efforts to unionize part-time faculty at Marquette.

WHAT DOES TENURE MEAN?

Classification of professors at Marquette is a bit complicated. There are actually 14 different titles for professors that can be broken down into two categories: regular faculty and participating faculty.

Regular faculty are tenured or are on a tenure track. They are full-time and are appointed to one of four ranks: instructor, assistant professor, associate professor and professor. Participating faculty are not on a tenure track, not entitled to continued reappointment and may be full or part-time. Participating faculty may be termed adjuncts, researchers, clinical instructors, visiting faculty, librarians or post-doctoral fellows, to name a few.

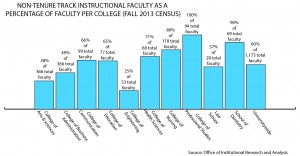

Only 41 percent of Marquette faculty have tenure or are full-time and on the tenure track this year, according to the Office of Institutional Research and Analysis.

As stated in the Marquette handbook, “tenure is a faculty status that fosters an environment of free inquiry without regard for the need to be considered for reappointment. Tenure is reserved for regular faculty who are recognized by the university as having the capacity to make unique, significant and long-term future contributions to the educational mission of the university.”

Daniel Maguire, a professor in the theology department, embraces the academic liberty afforded to him since earning tenure in 1973.

“Tenure is like a property right,” Maguire said. “You can’t just take away a house for no good reason.”

Contracts that come with tenure give instructors like Maguire the leeway to take positions that challenge traditional Catholic values without fear of losing their jobs. In 2007, for example, Maguire was denounced by U.S. bishops for his writings in favor of abortion rights and same-sex marriage, but that did not threaten his position at Marquette.

The termination process for tenured professors is extensive, typically involving a full trial. The guaranteed lifetime appointment, without any real chance of termination, presents challenges to higher education.

Critics of tenure argue the system provides no incentive to go above and beyond for students.

Brian Pratt, a sophomore in the College of Engineering, described several issues ahead with an electrical engineering professor to the tenure system, which he said allowed the professor to focus more on research than teaching.

“He was extremely distracted, often didn’t inform (teaching assistants) where we would be meeting and what we would be learning that day,” Pratt said.

These professors take up slots that could go to more energetic junior professors. Critics at Texas A&M University argue it is not that tenured professors are slacking, but they feel a “publish or perish” mentality in academia that comes at the expense of students.

Despite these criticisms, in 2010, then Provost John Pauly told the Tribune that “tenured professors still have incentives to excel and improve, such as pay raises, which are tied to annual evaluations and student course evaluations.”

But the biggest complication posed with the tenure system is a lack of financial flexibility. The salaries and benefits of tenured professors are fixed costs to a university that limit an administration’s ability to reduce tuition. These financial pressures, coupled with administrators’ desire for more flexibility in hiring and course offerings caused a shift in faculty make-up across America.

THE CASE MADE FOR ADJUNCTS

Despite soaring tuition prices, more than one million people work as adjunct faculty nationally at wages much lower than regular faculty, a substantial increase since earlier years. In 1975, adjuncts made up less than one-third of all faculty. The American Association of University Professors reports they account for nearly 70 percent of professors at colleges and universities, both public and private today.

“I wonder if colleges could survive without adjuncts,” said Donna Foran, an adjunct professor who teaches two introductory-level English courses this semester.

One explanation for this trend is that federal law abolished mandatory retirement for faculty in 1994.

Originally, adjuncts were designed to accommodate for faculty fluctuations each semester. If a tenured professor takes leave on sabbatical or if a department experiences a hiring season, adjuncts provide a quick fix to what could be an administrative nightmare. The use of part-time faculty is also essential in areas like foreign language and math where the demand for certain classes can vary greatly from year to year based on the size of the incoming class.

“Part-time faculty allow these departments to have the flexibility to hire faculty to teach certain classes while keeping class enrollments at optimal pedagogical levels,” said James South, associate dean for faculty for the College of Arts & Sciences. “That would be very difficult to do if they had to rely on tenure-track faculty alone.”

In certain fields like nursing and dentistry, it is common for professionals to teach a course or two while also working in their field full time. This is the case for Marquette’s dentistry and nursing faculty, of which 77 and 63 percent are part-time professors, respectively.

Some argue the real-world experience from adjuncts is more helpful to students than tenured professors who dedicated their lives to research. This is not always the case, however, for humanities and other disciplines where few jobs exist outside the realm of academia.

HARD TIMES FOR ADJUNCTS

Compensation for part-time faculty varies by department, but most fall in the range of $3,200 to $5,000 per course, said Andrew Brodzeller, associate director of university communication. Brodzeller also said this range is higher than many other institutions in the area.

Total average yearly income for part-time professors with no other means of income is difficult to estimate. Some professors teach a few courses at multiple universities to cobble together full-time employment. The Chronicle of Higher Education reports instances at other schools of non-tenure track professors living on food stamps and making less than $10,000 a year.

Living conditions of adjuncts have become such an issue that in November 2013, Democratic members of the House Committee on Education and the Workforce invited adjuncts to submit responses regarding their working conditions. Feedback from 845 adjuncts indicated low pay, inadequate working conditions and limited opportunity for career advancement. Because most of these adjuncts only worked part-time at a single location, 75 percent received no benefits regardless of whether the total hours at multiple schools add up to full-time status.

Job instability and unpredictable course loads are another problem attached to the adjunct lifestyle. Some respondents explained they are not notified as to whether or not they will be teaching a class until the day before the semester began. Most adjuncts agree to an at-will contract and can be dismissed at any time, for any reason.

It is unclear if any adjunct professor teaching at Marquette experiences the same problems, however.

“I’m quite happy here at Marquette,” said Paul Dworschack-Kinter, an adjunct English professor. “While I’ve seen other schools treat their adjuncts very poorly, I don’t feel that way about Marquette.”

Similarly, Mary Kazmierczak, a part-time professor, teaches one or two political science courses each semester. Fortunately, because she is employed as a librarian for the Milwaukee County Zoo, she can tell her employer what her teaching schedule is like for that semester and work around this.

“My situation is different because I am an alumnae,” said Kazmierczak.

Kazmierczak said she has always been given an office, which is a rare amenity for adjunct professors across the country. She did note, though, that the office sometimes had to be shared with other part-time faculty.

Dworschack-Kinter and Kazmierczak both talked openly about their situations. However, the Tribune emailed more than 15 other adjunct professors, but received few replies, most of whom said they did not want to discuss the issue.

Foran said one adjunct told her she did not feel comfortable talking to journalists. The lack of job security silences many adjuncts, but a nationwide movement to unionize may provide an outlet for part-time professors to negotiate wages and working conditions.

MU EFFORTS TO UNIONIZE

Unionization has not been universally welcomed by higher education institutions, especially at Jesuit schools. While professors at Georgetown University formed a union last May after citing the Catholic Church’s social justice teachings, Duquesne, another Catholic school, argued it is religiously exempt from bargaining with these professors.

Efforts were also made at Marquette to form a union. Maguire, despite having achieved tenure, lead the movement for a union by submitting a proposal to the university’s Academic Senate in December. The proposal called for a “forum” for discussion.

“I termed it a forum because that is not a very threatening thought,” Maguire said. “Since the 19th century, all the popes have defended the rights of workers to unionize.”

The proposal is currently under review by the Subcommittee of Part-Time Faculty. The subcommittee will meet again by the end of February.

William Fliss, co-chair of the Committee on Faculty Welfare, expects a recommendation for the forum to come out of the subcommittee’s work. This recommendation would then go to the Senate for deliberation.

Though this may sound promising to some adjuncts, others, like Foran, do not want to get their hopes up.

“One person complaining is nothing, but a whole group of them really says something,” she said. “However, it’s unrealistic to imagine administrators and full-time professors giving part of their salary to us. So where would they get the money to pay us more?”

Students also voiced concern over policies for adjuncts.

“Marquette gets selective with their cura personalis ideal,” said Cooper, the student gunning for a tenured professor position. “If universities like Marquette are stepping away from tenured professorships in favor of part-time workers to save money because they’re a business, they need to provide some sort of security measures for these people.”

Even if Marquette’s administration decides to support an adjunct union, the legal and financial challenges may take a few years before anything is implemented, as was the case at Georgetown.

THE EFFECT OF ADJUNCTS ON EDUCATION

The effectiveness of adjuncts at Marquette are measured mostly through voluntary student course evaluations and faculty observations. At a department meeting before the semester started, Foran was told course evaluation ratings for adjunct professors were higher than for the university as a whole last semester.

But a higher rated course evaluation does not necessarily equate to more effective teaching. Some critics of adjunct professors claim part-time professors give easier exams because if students do not receive the grade they want, they will write a bad evaluation that may result in termination for the professor.

Contrary to that theory, however, a Northwestern University study found adjunct faculty actually outperform tenured professors in introductory course. Students in classes with adjuncts were more likely to take further courses in the subject area and receive higher grades. The research was restricted to Northwestern faculty and students, though, so it is unclear whether this holds true at other institutions.

Regardless of adjunct effectiveness, schools received criticism for relying too much on part-time faculty to teach these introductory-level courses. Upper-level courses are typically reserved for tenured faculty, so the choice made by students to pursue a particular field usually falls onto adjuncts’ shoulders.

“We’re putting our weakest foot forward,” said Maguire, who said he has not taught Theology 1001 in several years.

Although Kazmierczak said adjuncts were effective at Marquette, she said the question ought to be left up to the students.

“Students who come to Marquette are expecting a quality education,” Kazmierczak said. “How much is your ($35,480) education worth?”