As the violence and unrest continues in Syria, James Foley, the Marquette alumnus and international freelance reporter who was kidnapped in Libya in April 2011, has been captured in the war-torn country. In recent weeks, Foley’s family has spoken publicly about his Nov. 22 kidnapping in an attempt to raise awareness about his capture.

Foley was reporting on the ongoing conflict in Syria when he was abducted from his car in the northwestern part of the country. He was en-route to the Turkish border in the village of Taftanaz. He was most recently working for Agence France Press but has also done work for Global Post in the past.

Foley’s family came forward in early January with news about his capture after six weeks of private search attempts turned up with no new details.

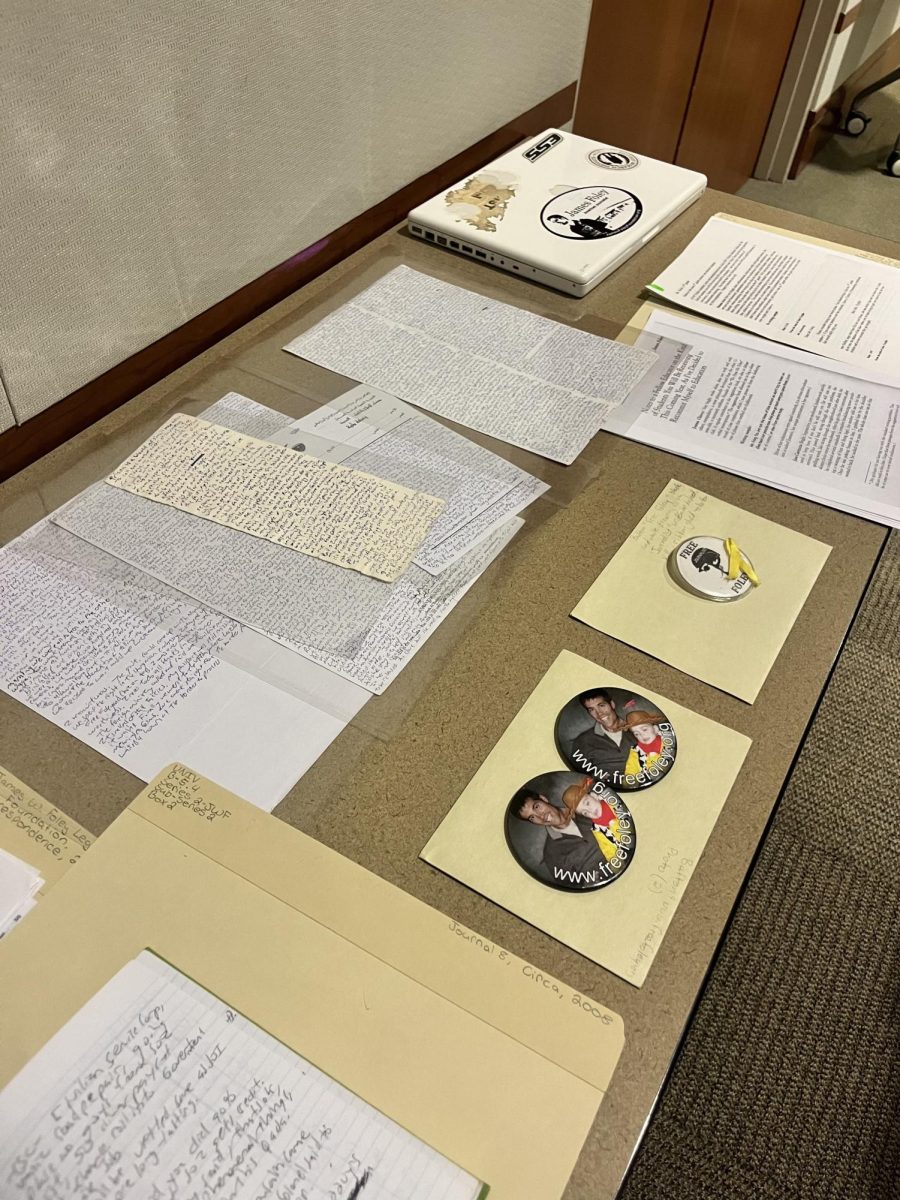

The Foley family created a website, www.freejamesfoley.org, to give updates on their search and to give people the chance to sign a petition asking for Foley’s release.

Andrew Brodzeller, senior communication specialist for Marquette, said Marquette has not received any additional information about Foley’s capture.

Foley spoke on campus in fall 2011 about his experiences in Libya at both the Lucius W. Nieman Lecture and a panel sponsored by the College of Communication entitled “Diederich Ideas: Reporting From the Front Line.” He was joined on the panel by Meg Jones, a reporter from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel who focuses on veterans and the military, and Herbert Lowe, a journalism professional-in-residence at Marquette.

Lowe said students who attended the panel were impressed by Foley’s discussion of his wartime experience in Libya and proud of his connection to Marquette.

“I was impressed by his humility,” said Lowe. “He was not portraying himself as a super-person, but as someone who was committed to his job.”

A Jan. 6 Global Post article about Foley said that Syria was one of the most dangerous places for reporters in 2012, with 28 recorded deaths and several kidnappings. Lowe said the statistics are concerning and that protecting journalists should be a major priority.

“It is a dangerous world, and they (front-line journalists) are there to help us understand why,” Lowe said.

Louise Cainkar, a social welfare and justice assistant professor at Marquette, said kidnapping journalists is not something that has typically occurred in the Arab Spring revolutions.

“I am not sure whether his status as journalist is the key in this case (Syria),” Cainkar said.

Cainkar said kidnappings tend to be used as an attempt to bargain with those interested in keeping the hostage alive.

She added that the situation in Syria is highly unstable since no one is “in charge” of the country. “This condition makes resolving his case extremely difficult,” she said.

“The Syrian people have suffered a long time under dictatorship, and that sense of having been disempowered and crushed as human beings is strong,” Cainkar said.

Foley’s kidnapping adds to what has been a chaotic and troubling year for journalism abroad. According to the International Press Institute, 132 journalists have been killed and several others have been kidnapped during the year 2012 — the highest number of deaths since the IPI began tracking the state of journalists abroad in 1997.