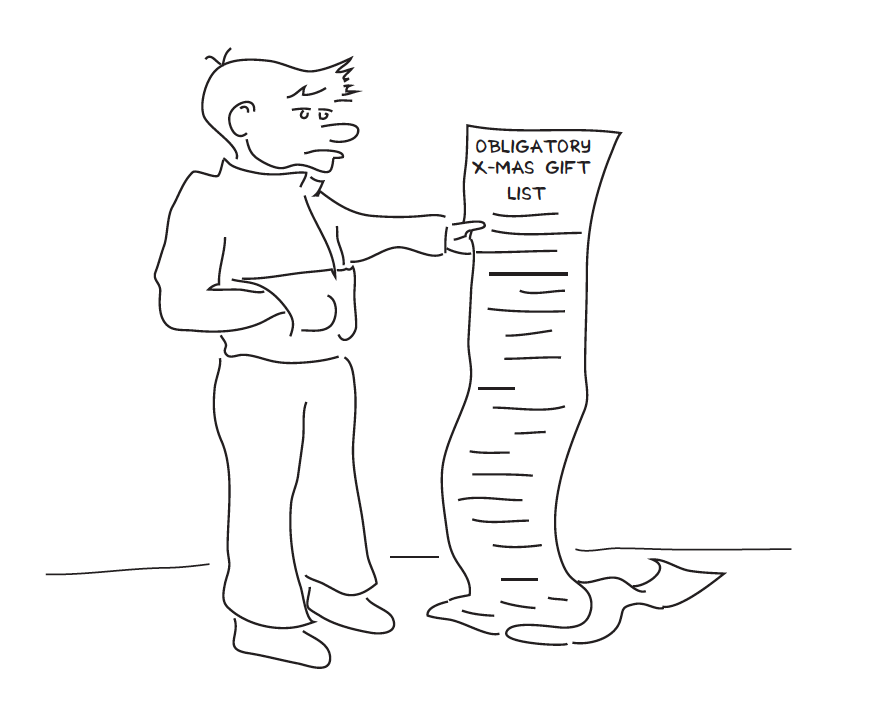

We’re all counting down the days until the semester ends, but as the horror of finals approaches, another dreaded task looms on the horizon: buying next semester’s textbooks.

It’s no secret that these books cost an arm and a leg. And what’s even more frustrating than spending a couple hundred dollars on a textbook is not even needing to use it during your class.

If you’re really lucky, your professor will require you to buy a textbook written by none other than her or himself. This situation isn’t necessarily bad, though. It means the professor is knowledgeable enough to have a published book about whatever he or she is teaching you.

But this also means that, depending on the agreement reached between the publisher and the author regarding the collection of royalties, these professors could be profiting from you as a student. Even if it is a small amount of money, that fact alone raises an ethical concern. It also raises the larger problem of instructors using their classrooms in other ways than their intended purposes: to teach.

Students reported that in last semester’s Foundations for Business Leadership class, they were required to buy a textbook directly from their professor, even if they could find it cheaper somewhere else, like Amazon.com. If they did not purchase the book from the instructor, they would be docked points from the class.

Why does it matter where students bought the book as long as they had it? Did this professor misuse his authority? (The professor in question disputed the students’ description of his course in an email but did not provide further explanation as of press time).

In at least one professor’s section of the broadcast and electronic communication capstone class, a required course for BREC majors, students are required to produce videos about Marquette for the university’s YouTube account. Again there appears to be a problem. These students are paying to attend Marquette; it shouldn’t be mandatory for them to use their skills to promote the university.

And just last week in a communication research methods class, a guest speaker from a research company used the class of nearly 120 students to function as a “mock focus group,” asking the students questions about their thoughts on her client’s brochures. She did not inform the students that she intended to actually give their feedback to her client until one student asked at the end of the class. The researcher never asked for consent, which is especially ironic in a class that teaches the necessity of obtaining consent for research.

The whole point of a “mock focus group” is to simulate an actual focus group. Students in the class had just been told that a focus group consists of seven to 10 people. Because this “mock focus group” was open to participation from nearly 120 students, the entire purpose of the day’s class, valued at around $72.91 per person, was rendered void.

The professor of the class said she intended the exercise to be purely demonstrational and was very surprised when the researcher said she would be reporting the data to her client. She had also thought the researcher would ask for volunteers from the class to come to a table at the front of the room to represent a focus group instead of surveying the entire class.

These situations, while rare, pose enormous ethical questions. At a Jesuit university where every student is required to take at least one ethics class in order to graduate, there seems to be a disconnect between the ideals taught and what’s actually being practiced in certain classes.

We encourage professors to reflect on their choices of required textbooks, projects and guest speakers, among other things. These decisions all have explicit value, but their unintended consequences are sometimes harder to recognize.

We are regularly encouraged at Marquette to think deeply about the implications of what we do. We ask our faculty to do the same.