SPRINGFIELD, Mass. — Most nights, it is nothing more than an industrial town filled with people leaving their blue-collar jobs and heading home. Lit up by headlights and filled with the sounds of honking, manufacturing plants whirring and the occasional cuss word spewing out of the mouth of an angry driver.

This Saturday, August 12, is not most nights.

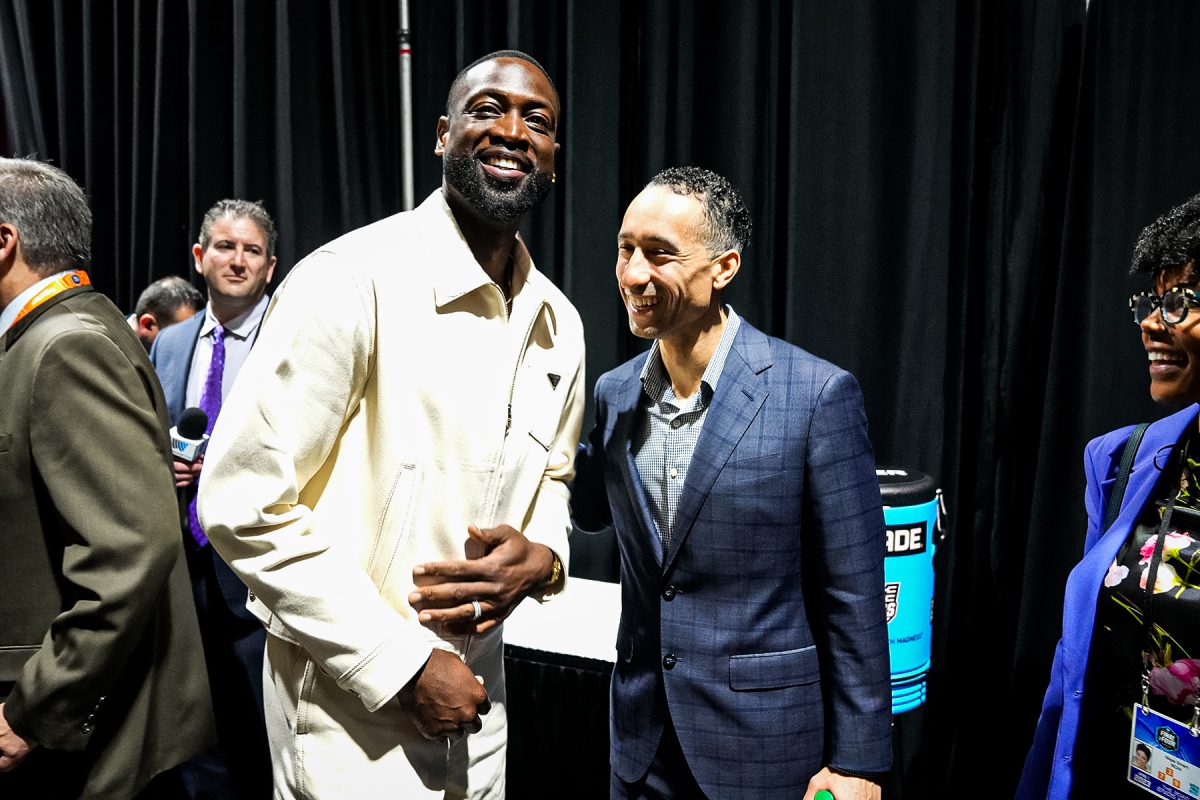

The biggest names and best players in basketball have shown up for the 2023 Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony, ready to transcend from legends to immortals. Among the group is former Marquette men’s basketball guard Dwyane Wade. He may be noticeably shorter than some of his fellow inductees, but there is an aura about him nobody can emulate.

Outside of Symphony Hall, the place in which Wade will be enshrined, stands a group of screaming children from the Boys & Girls Club of Springfield chanting “We want Dwyane! We want Dwyane!” He is the attraction. The show starter and the show stopper.

Wade, a first-ballot inductee, is the first Marquette player to be elected to the Hall of Fame.

“I went to Marquette as Prop 48. I was academically ineligible my first year. A lot of people like Coach Crean promised me a scholarship, but didn’t even know he can give me a scholarship because Marquette has never took a Prop 48. So to hear those words, and to say I’m the first to hope I’m not the last,” Wade said Friday. “But it means everything. Marquette gave me an opportunity that a lot of people didn’t want to give me.

“When they heard I was struggling with my ACT test, and my scores, that phone stopped ringing, the letters stopped coming, and Marquette stayed through it all. It’s a special relationship that we have, and I’m very thankful to represent this university.”

He’s had his eyes set on becoming a hall of famer for years, even writing in his high school yearbook that he would retire from the NBA as “one of the greatest to play the game.”

“I started writing my Hall of Fame speech when I was 17 years old,” Wade said June 22 in a press conference, “because of the work that I put in, the dreams that I went out and did, I went to fight hard to get.”

■ ■ ■ ■

Wade has known for months what Saturday night represents. But now, being here, it takes on a new meaning.

Sitting front-row, Wade, dressed in an all-white suit, looks at the camera before his pre-speech introduction video plays. The crowd erupts, easily the most emphatic reaction of the night. Once the video ends, he gets up and walks to the podium situated on center stage of Symphony Hall. All eyes are on him, nothing he isn’t used to.

Allen Iverson, the No. 1 overall pick in the 1996 NBA Draft and 2001 NBA MVP, sits attentively to the left of Wade. It’s no coincidence Wade chose Iverson to welcome him to the hall, he wore the No. 3 because of Iverson.

Wade could have used his speech to talk about all of his achievements and accomplishments. After all, he is a 13-time NBA All-Star. But, in typical Wade fashion, he spoke about others — having his “loved ones” stand up one-by-one for a special recognition. All of his children, his wife, sister, mom, former teammates and many others were asked by Wade to stand.

He, once again, used his platform to highlight just about everybody but himself, including his former head coach Tom Crean and former teammate Travis Diener, both of whom were in attendance.

At the end, his father, Dwyane Wade Sr., went up to the stage too, joining his son in all the glory.

Legacy. We in the Hall of Fame dog

pic.twitter.com/oBP7SVnG6r

— DWade (@DwyaneWade) August 13, 2023

His final words: “We in the Hall of Fame dawg.”

Immortality achieved.

■ ■ ■ ■

All the fanfare, attention and histrionics came about two decades after Wade was known more for his low standardized test scores than his basketball ability.

Wade grew up two hours south of Milwaukee, in Washington Park, a neighborhood in South Side Chicago, Illinois. He attended Harold L. Richards High School in Oak Lawn, a suburb of the city.

Despite his talents on the court, his academic struggles meant he received offers from only three college basketball programs (Marquette, DePaul and Illinois State). He chose to play for Crean and the Golden Eagles, arriving in Cream City in the fall of 2000.

“I truly believed in him as a person and was willing to fight for him if that’s what was needed,” Crean said. “Fortunately, it wasn’t needed. Father Wild believed me. His talent was going to come out in time I felt, but most importantly, I wanted to see him be successful.”

As a first-year at Marquette, Wade was academically ineligible to play due to the NCAA’s then-Proposition 48 rule and was forced to sit on the sidelines during games and stay in Milwaukee when the team traveled on the road. He spent the year studying to improve his academic standing and hitting the gym to work on his game.

“It started with his shooting, his ball handling and his footwork on both ends. We wanted him to learn every position so that he knew the value of how to make his teammates better and knew so many different ways to attack and defend,” Crean said.

“We wanted to treat him like he was as important as anyone playing, because he was. He was hungry but he needed to be pushed to really grow and those were ways to do that.”

After a year on the sidelines, Wade was allowed to play.

His sophomore season (2001-02), despite ending in the first round of the NCAA Tournament, proved what Crean already knew: Wade was a gem. The 6-foot-4 guard averaged 17.8 points per game and the Golden Eagles finished 26-7.

“That year showed that he had potential to take over games, not only with his scoring but with his defensive activity and his passing. It was starting to come out for him,” Crean said. “By his last year, the game had slowed down for him unlike anything I’ve ever seen in someone that age.”

But it was his final year at Marquette that put his jersey in the rafters of the Al McGuire Center and Fiserv Forum. He averaged 21.5 points per game, was named the 2002-03 Conference USA Player of the Year and earned the first triple-double by a Golden Eagle in almost a decade.

Wade and the Golden Eagles’ trip to New Orleans in 2003 didn’t end the way they hoped — being torn apart by the Kansas Jayhawks in a 94-61 rout in the semifinals — but that didn’t matter. Marquette was back, and everyone knew it.

Three months later, Wade was selected as the No. 5 pick in the 2003 NBA Draft. And the rest was history.

After three seasons in the NBA, one championship ring and a Finals MVP award, Wade made his way back to the Bradley Center to become the first player in program history to have his jersey retired before earning a degree. In 90 years, an exception had never been made.

Dwyane Wade (@DwyaneWade) has his #3 jersey retired at halftime of #14 @MarquetteMBB‘s 69-62 victory over Providence (@PCFriarsmbb) on February 3, 2007 #mubb pic.twitter.com/P6eo7rVFxA

— Marquette Overload (@MUOverload) August 12, 2023

He will now be visible in the hall, the iconic No. 3 Heat jersey he wore for many years, hanging in the brand new “Hall of Honor” exhibit.

Immortality displayed.

■ ■ ■ ■

Everyone knows that Wade is an owner of NBA team Utah Jazz, WNBA team Chicago Sky, Wade Cellars and a bevy of other businesses. Some know Wade started the Tragil Wade-Johnson Summer Reading Program, which aims to raise youth literacy rates in Milwaukee.

But Wade does much more off the court than what you’ll read in a press release. He is willing to help anyone and everyone, making extra time for those who have helped him. Jeff Strohm, an assistant while Wade was at Marquette, knows this better than anybody.

While an assistant coach of the Loyola Marymount Lions, Strohm was getting out of his car ahead of practice. Wade, unbeknownst to Strohm, walked up behind him and jokingly said, “Oh, big time. You don’t call me no more.” Wade had accidentally been calling Strohm’s old phone number. They chatted for a while about anything and everything, catching up after several missed conversations.

Watching this was Loyola Marymount head coach Mike Dunlap — now an assistant coach of the Milwaukee Bucks — who asked Strohm if Wade could speak in front of the men’s basketball team.

“I said, ‘Would you speak to our guys for about 20 minutes?’ And he (Wade) laughed and he goes, ‘No,’” Strohm said. “He goes, ‘You know me, Coach. I’m going a lot longer than 20.’”

Wade ended up talking to the team for an hour and a half.

“LeBron James and other guys were sitting there waiting to workout and he just kept talking to our guys,” Strohm said. “I was so proud of him. For him to do that just speaks to his generosity and who he is.”

■ ■ ■ ■

Wade’s speech had ended.

He hugged his dad — the third man on stage — and began his journey down the steps to a fully-standing crowd of awaiting family, friends and fans. Like a newly-coronated king, Wade held his head high, allowing everyone to bask in the moment. The only thing missing was the crown.

It was a great first night in his new home, the Basketball Hall of Fame, a place he will live forever.

As an immortal.

Others on Wade

2011 NBA Champion Dirk Nowitzki: “He’s one of the best two guards obviously to ever play the game.”

Winningest coach in NBA history Gregg Popovich: “He’s not just a competitor, he’s a super competitor. And somebody who does it with class, day in and day out.”

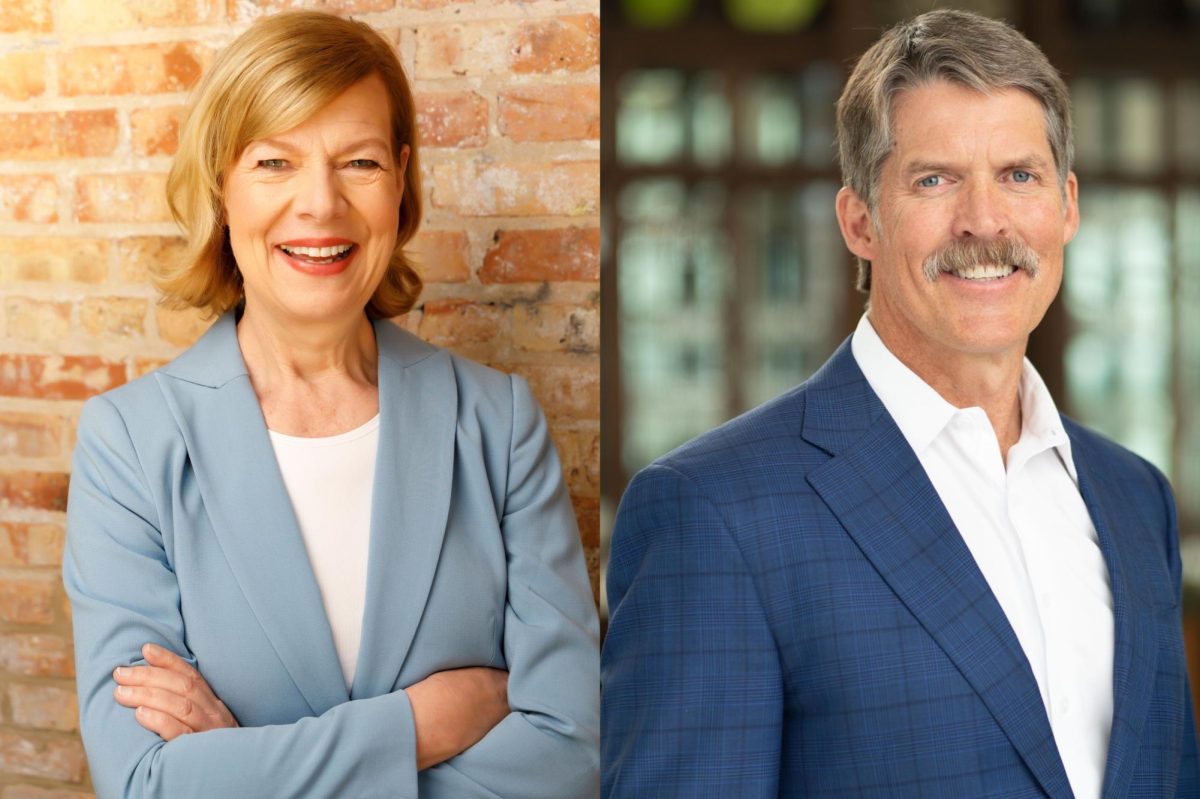

Marquette head coach Shaka Smart on Wade: “The great thing about Dwyane Wade is his willingness to share that (being enshrined) with all of us here at Marquette, and allow the Marquette fans and the people — especially the people that were around and supported him and went to school with him 20 years ago — to be a part of that with him.”

Wade on Wade

Wade on his career: “I’m most proud of being a pretty good teammate.”

Wade on sacrifice: “Sacrifice is a big part of my career. It actually should be one of the top pillars.”

Wade on versatility: “I learned how to be Robin, or how to be Batman. I learned how to be a part of Larry, Curly and Moe.”

Wade on utilizing his platform: “It’s my duty. It’s my job. It’s my responsibility to amplify messages and to amplify things that’s going on.”

A lesson Wade learned: “My mom always told me sow my seed and things will come back 10 times, tenfold.”

Wade on doing something first: “It sets the bar. I’m always about setting the bar, setting the standard.”

Required Reading:

This article was written by Jack Albright. He can be reached at jack.albright@marquette.edu or on Twitter @JackAlbrightMU.