Twenty years after leaving Marquette University, Alice Kehoe, professor emeritus of anthropology, said she still gets a pit in her stomach every time she sees the name Marquette.

“I was treated so badly and when I (left Marquette),” Kehoe said. “I got a written memorandum that I could no longer come on campus, I could no longer use Marquette email, or post mail or telephone or anything.”

After 31 years working as a professor in anthropology at Marquette and 23 additional years after her retirement, Kehoe emailed a formal letter to Marquette University President Michael Lovell this past March requesting back pay from being underpaid during her time at Marquette.

“Thank you for your inquiry and for your service over the years at Marquette. We are unable to grant your request for back pay prior to your resignation in 1999,” Cindy Petrites, assistant provost and chief of staff, said in the reply to Kehoe.

‘You needed the ‘Mrs.”

When Kehoe came to Marquette University in 1968, she had already seen and experienced discrimination as a woman in academia.

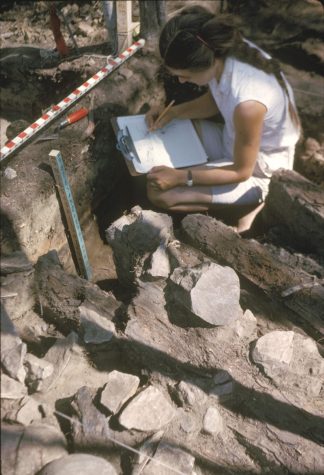

As a graduate student at Harvard University, Kehoe was forced to change her dissertation from archaeology to cultural anthropology and ethnography because her husband Thomas, who was also a Harvard graduate student, was also using archaeological methods for his dissertation.

The couple had separate degrees and dissertations, and were intentional about doing separate research projects; Thomas looked into prehistoric history and Alice focused on fur trade routes 400 miles away. Alice said despite this, her work was still challenged.

“The professors at Harvard told us that my husband’s archaeology project was fine, but for me, they said, ‘You can’t do your dissertation in archaeology, everyone will say your husband did it for you,’” Kehoe said. “There was no way we could do it together, no way we each (could) hand in our dissertation at the same time. It was just impossible.”

Thomas continued using archaeology for his dissertation.

Back then, Kehoe said women typically had to rely on their husbands in order to do archaeological fieldwork.

“You needed the ‘Mrs.’ if you wanted to do fieldwork in archaeology, unless of course you were a millionaire and could finance your own projects,” Kehoe said.

As a graduate student, Kehoe went to the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in Montana to do archaeological fieldwork, where she met Thomas, who had been working on the reservation for two years.

“We both loved working out there on the high plains, the mountains, working with the Blackfeet Nation,” Kehoe said. “We fell in love, everything seemed just right.”

Kehoe said she was able to do fieldwork because her husband was already working there.

“That was my ticket to being able to be a professional archaeologist – was that I had a male collaborator,” Kehoe said.

After Thomas’ career took them to the Saskatchewan province in Canada, where he established a heritage program, and Alice taught an anthropology course at the University of Regina, they moved to Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1965.

At her new job at the University of Nebraska, Kehoe said she felt discriminated against because her boss wouldn’t put her on the tenure track.

“My husband was physically threatening him actually, standing in front of him with his fist raised: ‘When are you going to put my wife on tenure track?’ And my boss said, ‘Never! I will never ever put a woman on tenure track,’” Kehoe said.

Both unhappy with their jobs, the couple found opportunities in Milwaukee, where Kehoe was hired at Marquette in 1968.

Although she was hired with the expectation that the anthropology department would be expanded to have five faculty members, which Kehoe said was normal for a department to function, they never did. She said there were only three anthropology faculty during her time at Marquette.

With the anthropology fad ending in the 1970s, Kehoe said Marquette had no reason to expand the program. Looking for more resources, she applied to open positions at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, but she said she wasn’t considered.

“They (UWM) have a PhD program in anthropology, so I would have had research support, graduate students, teaching assistants — I got none of that at Marquette,” Kehoe said.

She also applied to several positions at UW-Madison, and when she didn’t hear anything back, she wrote a letter inquiring about her applications. Both the chairman and secretary denied receiving them.

“An assistant in the program looking into discrimination was looking in a file cabinet in the chairman’s office and there are both of my applications, filed by the secretary even though he never answered either and denied ever receiving them,” Kehoe said.

She was essentially stuck at Marquette.

Treated like a child

When Carolyn Wells, professor emeritus at UW-Oshkosh, was at Marquette until 1999, she always felt like she was a child being watched by adults.

“You always kind of felt there was an authority structure hanging over your head. And I don’t know if the men felt that way, or if it was just women faculty like myself,” Wells said. “There was no sense of that at all at Oshkosh, the faculty felt empowered and could deal with administration on an almost egalitarian basis.”

Wells came to Marquette in 1972. After earning her PhD from UW-Madison in 1973, she transitioned from part time to full time. She helped establish a social work major and program and led the program to accreditation in the early 1980s.

In addition to receiving little university support for her program, Wells said she doesn’t feel she was paid equally during her 27 years at Marquette.

“I remember earning something like maybe … $56,000 a year,” Wells said. “I had probably been there many more years and done a lot more work. I had also published four books by that time, so it wasn’t that I was a slog when it came to academic performance. And I was not happy about that.”

Kehoe said women faculty started sharing their salary information to see what was comparable, but they couldn’t ask men to do that too.

“I know I must have been underpaid, I’m sure the women faculty in my group would all say the same,” Kehoe said.

According to the National Center for Educational Statistics, the average salary for female full professors was $20,308 in 1975. Twenty years later, it increased to $58,318. However, the average salary for male full professors increased from $22,902 to $65,949 between 1975 and 1995.

Another issue for Wells’ financial state arose when she got divorced in 1982. As part of the divorce settlement, Wells’ husband wanted half of her pension, so she went to the human resources department at Marquette. But they told her she had none.

“If I hadn’t had that divorce, I would’ve been 55 years old before I knew I didn’t have a pension, and I think that had to do with being a woman,” Wells said.

She said she thinks the university didn’t follow up with her about not paying into her pension since she was a married woman, and her husband would ultimately support her.

While Wells said her day-to-day experience at Marquette was typical, the environment was often exhausting because colleagues and the administration were sometimes hostile.

“I figured I lasted there a fairly long time because I’m pretty nonassertive and I’ll pretty much try to do my own thing without bumping into the powers that be,” Wells said. “I was a kind of quiet, compliant faculty member, but that didn’t mean you didn’t experience the weightiness of the decision-makers.”

Becoming an ALPHA female

After Carla Hay, retired professor of history, married her husband on New Year’s Eve in 1966, she was not expecting to receive a tuition bill from the University of Kentucky notifying her that her state residency classification had been changed.

“I had been reclassified as an out-of-state student because I had married someone from Tennessee,” Hay said. “I’d only been in Tennessee twice in my lifetime … It’s a common law approach to women. Once you’re married, you’re no longer really an independent agent.”

She wrote a letter protesting the reclassification because the change would dramatically increase her tuition. The University of Kentucky finally relented, granting her classification as an in-state student, but this time they based her identity on her father.

“They did it on the grounds that, not that I was a Kentuckian, who had lived all of her life in Kentucky, but that my father was a Kentuckian, who was a taxpayer,” Hay said. “It was just kind of a different world that you’re functioning in.”

Hay said when she applied to a tenured track faculty position in the history department at Marquette in 1973, other history faculty were hesitant to hire her.

“There was concern that my husband would essentially have two votes in department meetings … that I would do whatever he told me to do,” Hay said. “His voice would carry too much weight and ignore the fact that we had Jesuits in the department at the time that didn’t vote the same way on issues.”

Hay was the first woman hired on the tenured track line in the history department.

In academia, a tenured position is an “indefinite appointment that can be terminated only for cause or under extraordinary circumstances such as financial exigency and program discontinuation,” according to the American Association of University Professors. Securing a tenure position also helps “safeguard academic freedom, which is necessary for all who teach and conduct research in higher education … free from corporate or political pressure.”

She said despite efforts from her husband to hire another female faculty on the tenure track, the next woman, Leslie Knox, was not tenured until 2008.

Hay said it was not uncommon for women to be scattered throughout the university in different departments and colleges at that time.

“It’s not unusual in academia to essentially have academic silos,” she said. “You only really know people in your department, maybe a few other disciplines … but it makes information sharing, it makes seeing what the administration may or may not be doing, very hard to find out, but we became very informed about some of those issues.”

To foster support and create a unified voice for women across campus, women faculty joined together to form ALPHA. Carolyn Asp, former professor of English, first proposed the committee and established ALPHA in 1982.

Members of the group chose this name as a way of “underscoring the intention that this grass-roots initiative was the beginning of an important chapter in the University’s history,” according to an ALPHA summary handout Hay provided.

Women support groups were becoming common at that time because of the evolving women’s movement and they wanted a group that would support their professional aspirations in the workplace.

After Lynn Turner, a professor emeritus from the College of Communication began working at Marquette in 1985, she started seeing a lack of female representation throughout the university. She decided to join ALPHA a few years later.

“The number of women full professors compared to men … it was laughable, unbalanced. Even when I was promoted to full, maybe I was fifth or sixth full professor in the whole university, which is absurd,” she said.

Kehoe and Wells also joined ALPHA. Wells said the group would have potluck dinners at each other’s houses and these gatherings helped her feel more comfortable at Marquette.

However, while Turner noticed a lack of female full professors at Marquette, it was more of a larger systemic and cultural issue for her – rather than something someone could just blame on the school. Turner retired this past December 2021, and said she saw more female faculty being hired and more progress towards equality between men and women overall.

By 1985, Hay said there were more women being hired on tenured track lines. Some administration members also began attending some ALPHA meetings.

“(Administration) essentially recognized the group as having some stature and we were able to combine them and nominate people for university committees,” Hay said.

Hay said one of the group’s big successes was having the first female, Janet Boles, hired on a tenured track in the political science department, despite having many full faculty opposing.

While the members of ALPHA felt there were disparities between men and women, Turner said her communication department addressed potential pay disparities the best they could.

“(My department) was chaired by a man and he remained the chair for an extremely long time, but I would classify him as a feminist,” Turner said. “He definitely went to bat for the women in the department to get catch-up raises and merit raises, but not every year. It was not always in his power – never really was in his power – to do as much as he wanted to.”

While deans are able to parcel out raises in their own department, money is given out by the administration for the department as a whole, not for individuals. This way of distributing pay is still used at Marquette today.

“He could go to the dean and ask, but he couldn’t generate it himself so his hands were a little bit tied,” Turner said. “We were all underpaid.”

The position of the dean was male-dominated for many years, and because many of them left those higher positions to work in faculty, they brought that dean’s salary with them. This only further heightened any pay disparities that were already happening among faculty.

With the help of John P. Schlegel S.J., former dean of the College of Arts & Sciences, in 1986, ALPHA also established an interdisciplinary minor in women’s studies, which has been renamed gender and sexuality studies.

By 1997, the organization began to dissolve after several of the founding members had retired or moved on to other schools, and it became difficult to attract newer faculty.

“It shows that people who are motivated and willing to put in the work can accomplish an awful lot, and in a few short years, the organization did make a significant difference,” Hay said.

From four to two

Around 1998, Wells received a phone call from a former Marquette administration member who had recently been fired. They told her that Marquette was planning to close both the social work and dental hygiene programs and advised her to connect with the dental hygiene program.

“We both worked very hard to save our programs, but it became very clear to me that that wasn’t going to work,” Wells said.

Wells also tried to work with the nursing program to see if she could combine the programs, but she said she had already worked so hard to get the undergraduate program accredited, with little recognition from the university. She didn’t want to do all that work again.

Kehoe said she, Wells and criminology professor Richard Zevitz were separately told in spring 1999 that their programs were being closed because the department would be restructured to a full sociology department. They were asked to immediately resign.

Wells left, accepting an open position at UW-Oshkosh.

“I wasn’t asked to leave, but I wasn’t given any help in remaining,” Wells said.

Although all three had successful programs, Kehoe said Zevitz, who had the largest student enrollment for criminology, was able to show that he had earned his right to stay. She also said that “his attitude was manly,” which made the Academic Vice President back off.

“He met them man to man, like ‘how dare you challenge me?’” Kehoe said. “(Carolyn) and I were just beaten down. Every three weeks we would go and have another appointment, and it was the same thing, no matter what she or I said.”

A similar policy regarding the elimination of tenured faculty due to department restructuring still exists at Marquette.

Allison Abbott, chair of the University Academic Senate and professor of biological sciences, said that structural changes exist in Marquette and other universities.

“There’s essentially your spot, you got tenure in a certain department but that department might not exist. So there are times where that sort of very radical structural change can happen,” Abbott said.

Abbott said departments may be closed if there is no longer student demand.

“If there’s no longer a demand for a certain area of study and so we can’t keep going to some department or college where there’s no students – that’s a pretty extreme circumstance,” Abbott said.

With no income and being 63 years old, Kehoe wanted to wait until she was 65 before collecting on her pension from the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America, which Marquette is part of, and her Social Security. She was also financially constrained by her divorce.

“He took everything he could, I had to buy him out of our house. I didn’t have money to live on, so I kept on insisting,” Kehoe said.

She was persistent, eventually negotiating that she receive one year’s worth of salary and medical insurance for one year.

“That was the best I could negotiate. I tried and tried. My last months were very, very bitter. That wasn’t a slap in the face, it was a kick in the gut. Dr. Wells and I, we couldn’t believe that after all the years that we had been so successful,” Kehoe said. “To get so little from Marquette, it was a horrible feeling.”

Kehoe and Wells resigned in June 1999, leaving just two full female faculty members.

“Getting out of Marquette is the best thing that’s ever happened to me,” Wells said.

Turn of the millennium

Although ALPHA dissolved in 1997 with the most visible success of establishing a women’s studies program, conversations about equal pay and treatment for women in academia were still occurring in the late 1990s.

A month before Kehoe officially resigned, former Marquette University President Rev. Robert A. Wild announced he was forming a Task Force on Gender Equity. The task force was created in response to women faculty raising issues about gender equity related to the low number of women faculty at Marquette, especially in faculty in higher ranks, and general discrimination.

Hay was one of the committee members. She said an issue for women then and today is that they’re uncomfortable with negotiating their starting salaries.

“If you go in making 2, 3, 5, 10 thousand less than a male who is hired for the same kind of job, that cycles on with you because oftentimes everybody then gets the same percentage raises,” Hay said.

With Wild’s visible efforts to address gender equity, Kehoe said she thought he would reach out to her and Wells to return. But he never did.

“Possibly he didn’t know, but I don’t think he didn’t because the thing that should have stood in front of him, (was that) Marquette had only two women full professors,” Kehoe said.

The Report of the President’s Task Force on Gender Equity was released in 2001, after two years of surveying full-time faculty and department chairs and compiling quantitative data about salaries, workload, service and administrative opportunities.

Some findings indicated that there were significant gender differences in salaries, access to and appropriate salary of department chairs and attainment to the rank of associate professor. It also showed that faculty experienced significant levels of gender-based discrimination, which sometimes turned into harassment.

During the 2000-2001 academic year, only eight of 122 full professors were women. Additionally, 63 out of 232 associate professors and 76 out of the 182 assistant professors were women.

After the report was published, Wild wrote a letter to the editor to the Milwaukee Business Journal, announcing several strategies to address these issues. Some of these included creating clearer policies and procedures for appointing and evaluating deans and department chairs, determining salaries, mentoring faculty and measuring progress toward promotion and tenure. Wild tasked academic deans with investigating potential inequitable salary at hire.

Wild wrote that Marquette had allocated money in the following fiscal year’s budget to address those disparities.

Wells said Wild’s commitment to addressing salary gaps was positive.

“I want to congratulate them (Marquette) on that. I did talk with one woman later who I had taught with, and she got a substantial raise that year,” Wells said.

Still evaluating twenty years later

Since the report, there have been persisting gender equity issues and subsequent efforts to address them.

Jennica Webster, co-director for Marquette’s Institute for Women’s Leadership and an associate professor in the department of management, is currently part of the Pay Equity Task Force. A cohort of faculty worked with the Academic Senate and the Committee of Diversity and Equity to establish the ad hoc committee in fall 2020.

Webster said the Task Force conducted a salary equity analysis, which will be shared at the next Academic Senate meeting in May.

“We do not see pay differentials attributed to gender across the university that cannot be explained by variables such as academic rank or academic department,” Webster said in an email.

Webster said conducting a transparent salary equity audit can be important for pay perception. She added that showing people are paid equally for the same work is important to showing they’re valued.

“Salary averages are misleading figures. Faculty salaries vary by discipline, rank (e.g., instructor, assistant professor, associate professor, full professor), market and years in rank,” Sally Doyle, Assistant Provost for Budget and Division Operations, said in an email. “In general, staff who are at the same level would be paid within a similar range.”

In addition to concerns about equal pay, there are also differences between male and female faculty rank.

As of the fall 2021 semester, there are 44 full-time tenured female professors and 85 full-time tenured male professors, according to the Office of Institutional Research and Analysis. However, there are 111 male associate professors and 105 female associate professors.

Webster said the Gender Equity Task Force is planning to look at the length of time it takes for men and women and people of color to advance through faculty ranks.

“Now that we have instituted a transparent salary equity analysis where faculty are represented in those discussions, we want to make sure that people are advancing in ranks at a rate that reflects their work products rather than non-merit-based criteria such as gender and race/ethnicity,” Webster said in an email.

Despite these efforts, there are still women faculty who don’t feel supported.

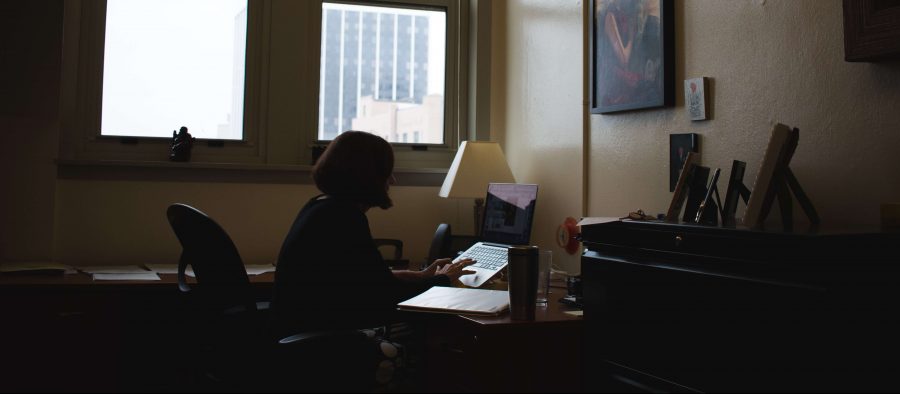

Jane Doe, a faculty member who asked to remain anonymous for fear of risking her employment at Marquette, works multiple jobs in addition to teaching. With all of these jobs, she earns just over $50,000.

“As a woman faculty member at Marquette, I not only teach my classes and try to do research but also take on a lot of extra service,” Doe said. “(Women) end up doing a lot more invisible service than men tend to do.”

Doe said she writes at least 50 recommendation letters a year and does her best to support all of her students in and out of the classroom.

While these responsibilities may take a toll on her mental health at times, she said enjoys what she does and the colleagues she works with overall.

“I think things are getting better, and the great thing about Marquette is that there is a really strong network of women … and there are some men allies as well,” Doe said. “But just because something appears to change doesn’t mean that it changes in reality.”

Hay said this idea of female faculty having additional service responsibilities is not new.

“There was initially an unwillingness to recognize that this was a problem – that you can’t have women doing this heavy service load, which is important to the institution, and yet, acting as if it in no ways impacted their other responsibilities,” Hay said.

‘A slap in the face’

This March, Kehoe reached out to the Office of the President after learning about women faculty receiving back pay from Princeton University.

In October 2020, Princeton announced it would pay nearly $1 million in back pay to female professors, after the Department of Labor conducted a review in 2014, finding that 106 female faculty were paid less than their male counterparts between 2012 and 2014.

“I thought, you know this is Women’s History Month. All this talk about equality and bringing equity to women, and all these slogans, all these posters, all these special lectures and meetings. I thought what the hell, I’ll write to Dr. Lovell. I mean, Dr. Lovell is a married man, he has a wife,” Kehoe said.

However, Lovell did not reply to Kehoe.

“Thank you for your inquiry and for your service over the years at Marquette. We are unable to grant your request for back pay prior to your resignation in 1999,” Petrites said in the email.

When asked why Marquette didn’t grant Kehoe backpay, Doyle said in an email that “the university does not publicly discuss confidential personnel matters.”

Although Kehoe wasn’t surprised with the response, she was really disappointed.

“I mean the least he can do is write me, or dictate a friendly letter ending, that ‘I’m sorry that we can’t do this,’ but getting an email back from one of his staff people was a slap in the face,” Kehoe said.

In an earlier version of this story, we inaccurately represented “full-time” as “full” in some areas, when referring to faculty. “Full” status deals with faculty rank, rather than the number of hours they work.

We also misattributed that Carolyn Wells said that she thought Marquette had improved by putting more women in administrative positions. She did not say this.

The Wire regrets these errors.

This story was written by Skyler Chun and Alexandra Garner. They can be reached at skyler.chun@marquette.edu and alexandra.garner@marquette.edu.