The sun beats down on the mask-covered faces of hundreds of frustrated, heartbroken and exhausted protesters gathered in the streets of Milwaukee. Closing down freeways, walking for miles on end, for days on end, they hold signs high.

“Enough is enough, end racism.” “I can’t breathe.” “Black Lives Matter,” are among the phrases written across cardboard.

Determined pleas for equity reverberated across the nation, making their way to demonstrators on Marquette’s campus. As the Black Student Union, the Native American Student Association and the Marquette Academic Workers Union organized separately for administrative change throughout the fall semester, a leitmotif emerged: a heralding call to reimagine the on-campus police force.

“This summer made it pretty clear that police violence is a very big issue, and intrinsically related to the way we deal with race on campus,” Sarah Kizuk, a member of the Marquette Academic Workers Union and doctoral candidate in philosophy, said.

From slave patrols to traffic stops, activists chart the evolution of American policing as one fundamentally marred by institutional racism. In southern slave-holding states in the early 1700s, militia groups of white men — known as slave patrols — were formed to control enslaved peoples. Every state that had not yet abolished slavery had slave patrols. Then, in the early 19th century, municipalized forces of predominantly white men emerged in cities such as Boston, New York and Chicago. These first police officers faced few standards for hiring and training, and corruption — including bribery and brutality — was widespread. Activists assert this trend has continued throughout the decades.

Although reforming, defunding and abolishing the police exist as different points on an activist continuum, Marquette dissenters insist immediate change is necessary — and intrinsically linked to the impending faculty layoffs.

“If you’re reading from left to right, where left is the least amount of change, you’d say reform, defunding next, and then abolishing,” Anthony Peressini, associate chair of philosophy, said. “Reform is something that has been tried a long, long time, and large numbers of people across the country have realized reform doesn’t seem to work.”

Common ideas for reform include the use of body cameras, bias training and de-escalation tactics. Research conducted on the use of body cameras among police officers suggests there is no statistically significant reduction in police use of force, even when officers know they are being filmed. Similarly, bias training and de-escalation tactics have had mixed to inconclusive results.

Defunding, alternatively, involves redistributing some fiscal resources away from officer militarization — including expensive riot gear and armored vehicles — and to communities of color that are policed, Peressini said. Funds could be reallocated to job and education opportunities, as well as community watch efforts to bolster safety, Peressini said.

Community-based violence prevention programs such as 414Life employ a public health approach to neighborhood safety, meant to target the root causes of crime. Among the causes identified: unaffordable housing, generational trauma and limited opportunities for economic and social mobility. Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett similarly called for a public health approach; under his proposed 2021 budget, Milwaukee would see a decrease in 120 police officers, although the $300 million Police Department budget would remain essentially the same, as the savings from the 120 officers would be spent on personnel-related costs.

Brooke Huerter, a senior in the College of Arts & Sciences, echoed those sentiments.

“I would love to see more community-based efforts to make sure our community is safe,” Huerter said.

Defundment and abolishment are not dichotomous, but complementary, Peressini said.

“The key to abolition is that it is very self-consciously wrapped up in the recognition that the police have been involved in unethical practices since their conception, after abolition and through Jim Crow,” Peressini said. “The work of abolishing slavery hasn’t been finished — it’s an ongoing project, and the police are a manifestation of how that is unfinished.”

Rather than defunding the police, the administration has elected to defund other key programs, Peressini said. Alongside announcements of 225 to 300-plus potential faculty layoffs, Marquette stagnated the job search for its Race, Ethnic and Indigenous Studies program this semester. The administration also announced its Hispanic Serving Institution initiative would no longer be a part of the university’s strategic plan. Additionally, in 2019 the College of Education faced a potential merge with another college on-campus, as well as cost-saving structural changes.

“We’re defunding, essentially, the faculty and resources on campus that can study, critically analyze and propose alternatives (to policing). It couldn’t be more misguided,” Peressini said.

Along with a recruitment decline due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the administration additionally cited a “demographic cliff,” or an anticipated decline of 15 to 25 percent of college-aged students by 2026, as reason for these measures. These projections come from economist Nathan Grawe’s “Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education,” and have been intensely scrutinized for its alleged prioritization of white, upper and middle-class families who could or would pay full-tuition for college. At Marquette, nearly 70% of the undergraduate population is white. More than 85% of the Class of 2024 came from the Midwest, mostly from Illinois and Wisconsin.

The university is adding new hires to its police force, however. Online listings from October of 2020 indicate Marquette is searching for a full-time police officer and communications officer.

“MU’s priorities are telling our students that police are how we solve problems and manage our relations with our Black and brown neighbors,” Jodi Melamed, professor of English and Africana studies, wrote in an email. “MUPD’s policing produces de facto borders around MU, rather than building bridges … and it disempowers our BIPOC students through racial profiling, instead of providing the structural and whole person support an REIS infrastructure would provide.”

The MAWU signed a petition over the summer calling upon the university to reallocate funds from policing to community alternatives, as well as to communities predominantly impacted by police violence. The petition also calls for MUPD to issue a statement condemning the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and Tony McDade.

In a campus-wide email penned by University President Michael Lovell following the police killing of George Floyd, Lovell announced a virtual mass to “pray for an end to racism.”

“I wish it was that easy,” Kizuk said. “I wish we could all bow our heads and solemnly pray for racism to end. That would be great.”

For Kizuk, it is clear more substantive efforts are needed.

“We need to be involved in real, hard work. This university needs to be involved in real, hard work. But sending out one-sided emails — that are quite tone deaf — certainly is not a great start,” she said.

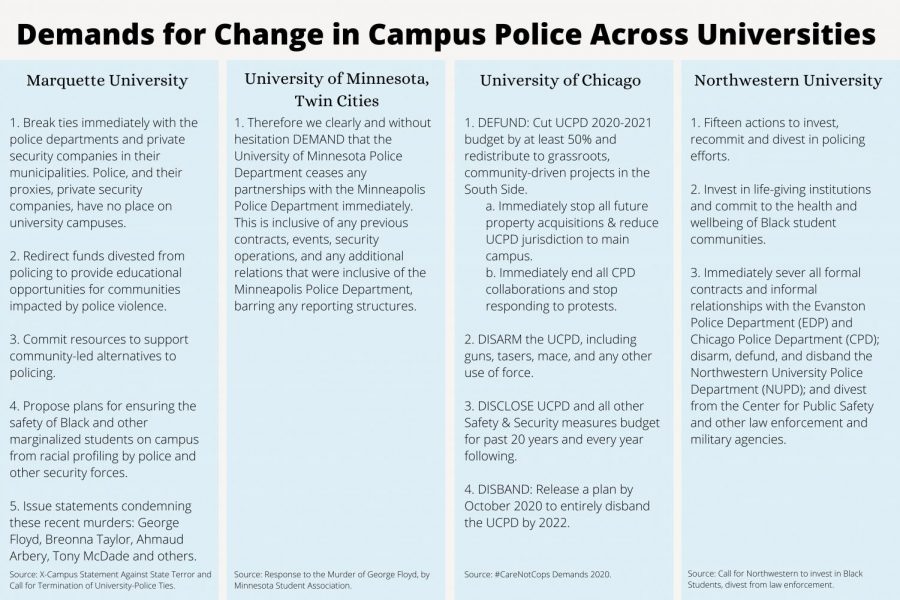

The MAWU petition follows in the footsteps of the demands made by the Minnesota Student Association at the University of Minnesota. The city of Minneapolis, where UMN resides, is the home of George Floyd and was the first to see protests this summer following his murder.

The statement demanded that the University of Minnesota Police Department immediately cut ties with the Minneapolis Police Department, and called for a response from the university within 24 hours.

The next day, the university’s president Joan Gabel issued a statement announcing that the senior vice president would no longer contract with Minneapolis Police Department for enforcement at large events and that the university police chief would no longer use Minneapolis Police Department for specialized services such as K-9 explosive detection units.

While UMN experienced changes to campus police, Marquette has initiated incremental steps for reform.

MUPD has agreed to have regular meetings with the Black Student Council to address community concerns. It is unclear if these meetings have begun or how often they will occur. This initiative is part of a larger program that came as a result of demonstrations held by BSC and its subsequent meetings with Marquette administration.

Other universities, such as the University of Chicago and Northwestern University, have faced similar stalemates.

At UChicago, student initiative Care Not Cops called for a four-part plan to defund, disarm, disclose the budget of and ultimately disband campus police. In August, the provost issued a statement announcing a multistep plan to improve UCPD. The plan includes renewing engagement with campus and local communities, identifying areas for action, surveying the community, forming a public safety advisory board and building on past improvements. This continued reform includes accountability, transparency, accreditation, diversity of officers and training.

Unsatisfied with reform, students have continued to demonstrate and call for stronger action.

Northwestern students have demanded that the university invest in “life-giving institutions” and focus on the well-being of Black students. In addition, they call for the university to cut ties with any and all police departments — including campus police — and other law enforcement and military agencies.

Last month the university’s president sent an email detailing announcing a community safety advisory board to strengthen community relationships and advisor administration. The university has also committed to regular meeting with student groups such as NU Community Not Cops.

Similar to UChicago, despite steps towards reform, student demonstrations have continued on campus.

Peressini said he experienced the transition from campus security to MUPD in 2015, and was concerned as soon as the process began.

“I’ve always been very uncomfortable, and was opposed to moving from a public safety institution on campus to full-scale policing activity,” Peressini said. “I never thought it was a great idea.”

As a private police force whose predominant authority is the Marquette administration — which is self-admittedly flawed in its failure to uphold racial justice initiatives — a natural barrier between MUPD and the student community will remain.

MUPD was unable to comment on the MAWU petition and the push for changes to campus policing.

“I don’t want to deny that some people have had good experiences with MUPD, and have felt safer or taken care of,” Kizuk said. “But what is absent from those experiences are the broader ability to be critical. Personally, I define defunding the police in more stark terms. For me, what it means on our campus is getting rid of the entire MUPD force.”

This story was written by Lelah Byron and Amanda Parrish. They can be reached at lelah.byron@marquette.edu and amanda.parrish@marquette.edu