The world must pay attention to the humanitarian risks facing certain South Asian and African countries that have resulted due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Education is one of the most important factors in determining a country’s human development index, a summary of achievement in education, healthy life and decent standard of living, and it is correlated with levels of poverty and measurements of gender equality. As schools close around the world to limit the spread of the coronavirus, citizens struggle.

After recently surveying 158 countries about their reopening plans, UNICEF found that one in four countries have not put a date out for allowing children to come back to the classroom.

In countries without widely accessible internet connection or computers, remote learning is not a possibility. Without education, children have turned to work in order to help their families who may need the extra income.

Beyond education, schools provide children with vital health, immunization and nutrition services, in addition to a safe and supportive environment.

This safety net collapses when they are out of school. They are exposed to more physical and emotional violence, which affects their mental health and makes them more susceptible to child labor and sexual abuse. When children are not in school, they are exposed to the perils of the adult world and thus forced to mature quickly.

The work they do is often unpleasant and dangerous, in addition to being illegal. In India, children may rummage through trash with little protective equipment for only a few cents an hour. In Kenya, they may turn to sand mining, the extradition of sand through an open pit. Education setbacks can be detrimental to countries that have just begun to make progress in regards to education.

In the beginning of the pandemic, India’s laborers, such as street peddlers or field workers, were unable to properly adhere to social distancing guidelines. They faced starvation as police used force against those caught violating lockdown laws. Hunger waged more fear in citizens than the virus itself.

According to UNICEF’s Children in India Report, extreme poverty in India has been reduced to 21%, the infant mortality rate has decreased by more than half, 80% of women now deliver babies in a health facility and two million fewer children are out of school. These advancements can become compromised as financial and educational instability arise.

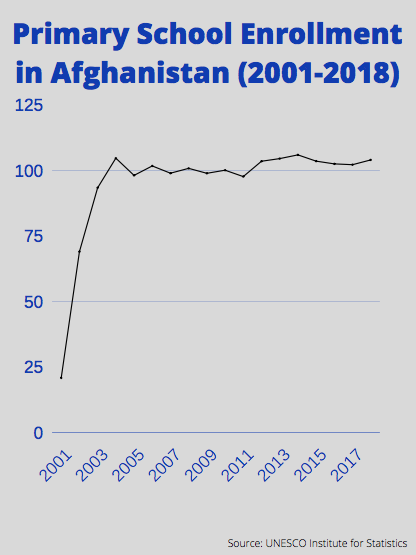

In Afghanistan, primary school enrollment increased from nearly 21% in 2001 to 104% in 2018, according to UNESCO. But in 2020, the coronavirus pandemic pushed millions of Afghans into poverty due to the health care system becoming overwhelmed and the country experiencing an economic recession.

Developing countries cannot afford for the pandemic to undo a decade’s worth of progress. The world already experiences vast inequality between countries and the gap will only become wider if increasing poverty goes unaddressed.

While COVID-19 restrictions are necessary, it is important to recognize that the world’s most disadvantaged will struggle the greatest as a result, especially countries that have a history of political instability. Even in the middle of a pandemic, we must not lose sight of developing humanitarian crises.

Governments must come up with creative ways to keep children learning. In Senegal, schools have spaced out classrooms and chairs. Some schools have shifted to learning outdoors. At home, children can continue to learn through magazines, books and radio.

The United States had only delivered $11.5 million in international disaster aid directly to private groups as of June 2020, with little humanitarian assistance reaching those on the front lines of the crisis.

Education must be prioritized and labor exploitation concerns must be addressed. These issues should be of worldwide concern. Developed countries should continue to offer medical and economic aid to countries in need. All countries have a moral duty to help humans who struggle, and countries able to offer aid in times of need should do so.

This story was written by Lucia Ruffolo. She can be reached at lucia.ruffolo@marquette.edu