This story is fictional and part of the “Opinions from the Future” series. It is a prediction of what our world may look like in the future in the aftermath of the coronavirus. This story is based on present-day data and available evidence.

The first case of the coronavirus was detected in the United States Jan. 20, 2020. At the time, the virus seemed miniscule and insignificant to the American population, as it originated in Wuhan, China. By the end of January, 9,976 cases were reported in at least 21 countries. The world had no idea what was yet to come.

A mere 85 days later after the first reported case of the coronavirus in the U.S., the coronavirus pandemic had spread at an exponential rate and quickly infested the world and everyone in its path. Just three months after the first person in the U.S. tested positive for the virus, the infection reached all 50 states, and America became the country with the most confirmed cases at 717,000 cases. Hospitals had insufficient resources and the spread of the disease looked far from over. The rise of numbers after that soon became a blur to the world as they continued to rise at unbelievable rates.

It is now May 1, 2021. The country looks back on the year it just had. Although governors have slowly lifted the stay at home orders throughout the year, the world needs a lot more time to heal and return to the state it was in before the pandemic. We might not ever return to life as we knew it before the coronavirus hit. We may never shake another person’s hand or travel so freely. But now, we walk the streets with knowledge about the safety precautions necessary to keep ourselves and loved ones safe.

As the world begins to pick itself up again, the effects of the coronavirus did not hit us all the same. The infection enlarged and exposed the already significant divide between high and low socioeconomic classes, especially for minority groups.

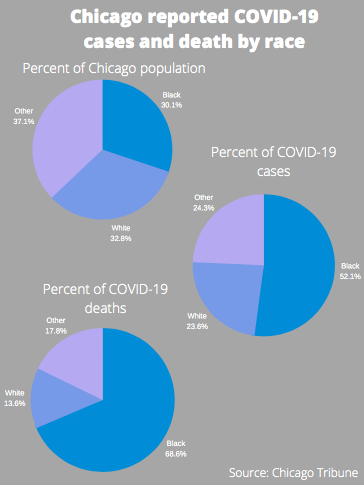

For example, West Garfield Park of Chicago, a predominantly African American neighborhood already under economic siege before the coronavirus, was disproportionately hit. The neighborhood already had a life expectancy 16 years lower than the surrounding white neighborhoods of Chicago. The pandemic did not help improve that statistic. Sixty-eight percent of the coronavirus deaths in Chicago were African American individuals despite African Americans making up just 30% of the entire city population.

People living in lower socioeconomic urban areas are more likely to live in overcrowded spaces and less likely to have access to healthcare that can provide treatment for the coronavirus. This made the virus spread like wildfire throughout these communities and the government did not do enough to protect them.

Those at a lower economic status are also more likely to work minimum wage jobs. These jobs such as grocery store, garbage and gas station workers, were deemed essential by state governments, which meant these individuals continued working regardless of the state of the pandemic.

This meant that those who worked essential jobs felt even more responsibility to continue working during fearful times in order to provide for their families. Many landlords still expected them to pay rent and services like water and electricity. Being at the frontlines meant these essential workers were the ones most exposed to the virus, with a very high chance of contracting it.

African Americans were also more at risk during the pandemic due to a high percentage of them that already faced fatal health conditions. African American are 50% more likely to have heart disease and 19% cannot afford to see a doctor.

Hospitals turned away patients with illnesses less severe than the coronavirus, meaning African Americans were unable to receive health treatment. Patients were expected to turn toward their primary care physicians for other medical issues, but those at low economic standings did not have any. The hospital was their only means for receiving what they needed.

The fact that racial and economic minorities were hit harder than any other social group indicates the continued neglect of these communities in American society. Structural racism and the deep divide between economic classes became even more apparent than before through last year’s coronavirus pandemic, and it caused the deaths of thousands of African Americans. They were disproportionately impacted and damaged, further perpetuating the tensions between these groups and disunifying them.

Communities of color, especially those in the lower economic class, are continuing to deal with the atrocities and damages they faced from the coronavirus. They must figure out how to get their lives back to normal when so many individuals from their own neighborhoods were taken away.

The stimulus package passed by the U.S. Congress should have included greater reparations for those unable to keep up with their health risks normally, let alone during a pandemic. More landlords could have been lenient on renters during the coronavirus, so essential workers did not feel like they had to work and risk their lives to continue financially supporting their families. Managers and owners should have provided their workers with protective gear if they were still required to work. Unemployment benefits should have increased to support individuals who were let go from their jobs due to the coronavirus.

The disregard for this kind of restorative action cost African Americans and other minority economic groups their lives, and they are now stuck to face it again and alone.

This story was written by Aminah Beg. She can be reached at aminah.beg@marquette.edu.