Immigration has been on everyone’s minds with the 2020 presidential election looming ahead, and it feels like a terrifying case of deja vu. The recurring feeling isn’t just because of hate crimes or xenophobic rhetoric — two things that precede the founding of the U.S. — but rather a combination of the two and their correlation with the possibility of Donald Trump’s second term as president being on the horizon.

Life for the majority of white, U.S.-born Americans will remain largely unaffected if Trump is reelected.

White Americans need to educate themselves on the faults of the immigration system and the narrative of immigrants. Doing so will ensure that citizens conscientiously use their vote in the 2020 presidential election.

The nation’s eyes were on Milwaukee last week after Clifton Blackwell, a local 61-year-old white male, was charged with a hate crime against 42-year-old Mahud Villalaz, a Peruvian-American citizen. Blackwell called Villalaz an invader, an “illegal,” and told him to go back to his country before he threw acid on Villalaz’s face. The left side of Villalaz’s face is now marked with second-degree burns.

Villalaz has been living in the United States for as long as I have been alive: 18 years. He is as “American” as I am, if not more, as he has been a participating, adult member in society all the while. Labeling this hate crime as “xenophobic” is, for lack of a better term, generous: it was unambiguously racist.

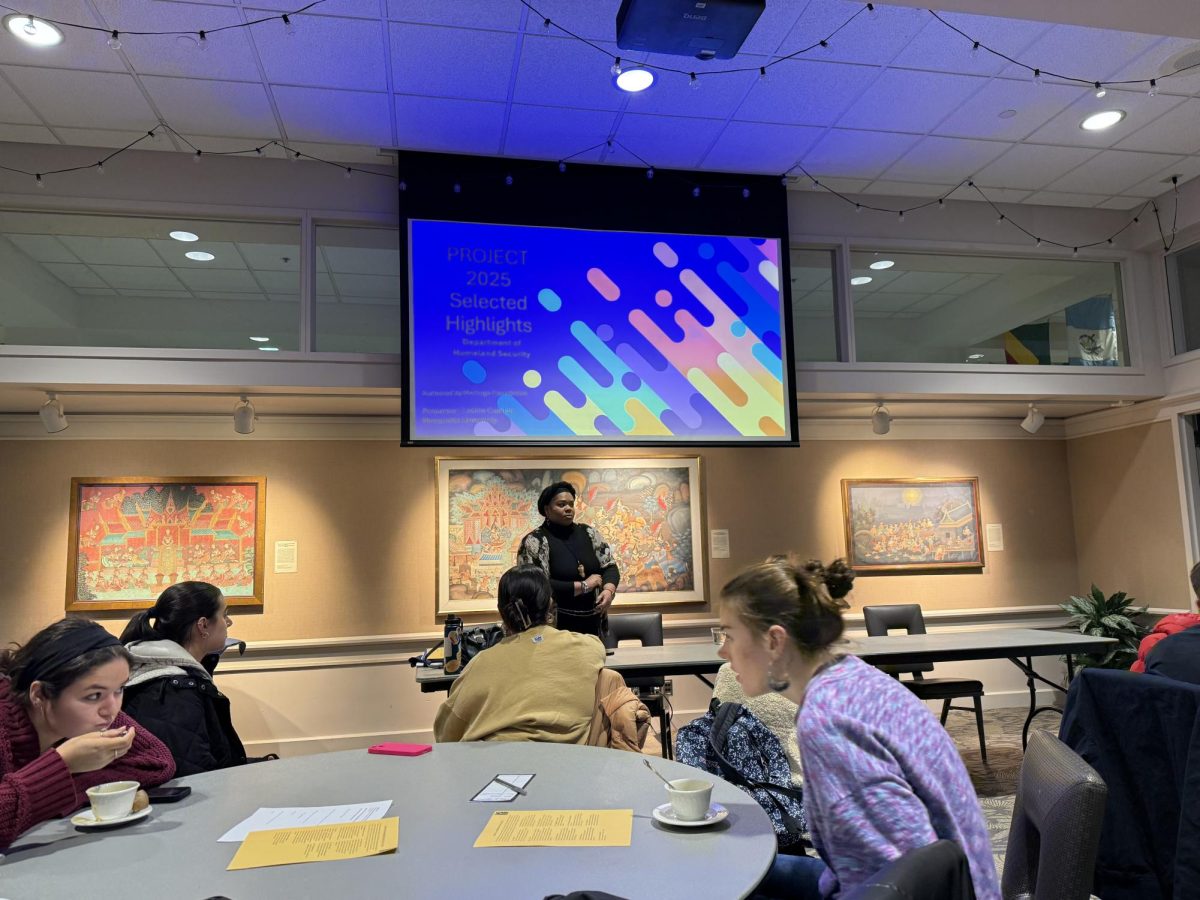

The day after the attack on Villalaz went viral, I went to an event held at Nō Studios, a creative arts space in Milwaukee. At the “Coming to Milwaukee: Immigration Stories,” several Milwaukeeans shared their experiences being an immigrant, being related to an immigrant or working with an immigrant in Milwaukee.

Each individual spoke for about five minutes. The stories were triumphant, heavy, admirable, sad and everything in between.

Some of the speakers talked about their first days at Milwaukee Public Schools, their relatives being forced to leave or their struggles of obtaining an affordable college education without citizenship. Other speakers emphasized asylum seekers’ lack of rights in the U.S., the success of immigrants as active participants in the Milwaukee community and the value of freedom over wealth.

Despite each speaker having completely different experiences, I found a thread of commonality among almost all stories, including themes of dedication, oppression and pride.

Looking someone in the eye and hearing an explicit, personal testament to their parents’ devotion to securing life in America for their child is as close as I — a white, born and raised U.S. citizen — can ever get to understanding the strength of an immigrant.

The bigotry under Trump’s administration will continue to test this strength as long as he is in office and as long as citizens continue to ignore the immigration crisis. Citizens’ civic duty to vote include educating themselves on the issues facing our nation. The immigration crisis — a human rights crisis — from the travel ban to living conditions in detention centers, to immigrant communities’ imperative contributions to U.S. society is essential to talk about.

The best way to do this is to become aware of events such as “Coming to Milwaukee” in one’s community. As Marquette students, we have easy access to related events because we are living in a metropolitan area. We must utilize them in order to use our vote wisely in the coming election.

As stated by one of Nō Studio’s speakers, “your one vote stands for millions of voiceless, undocumented individuals.”

Those millions have no say in a decision that will impact them as one of the groups most affected by the election. We, as, citizens must educate ourselves on the immigration crisis by listening to the experience of immigrants, specifically here in Milwaukee, and voting for a presidential candidate who will work for the rights of those whose voices are stifled.

Villalaz himself said that he feels supported nationally after the incident, stating that “it has been wonderful to see that there are many people who worry about others, not only Latinos but white people … everybody.”

To truly be supportive, these people that Villalaz mentions cannot only verbally accuse others of racism and xenophobia. They must actively work toward further educating themselves on all aspects of the immigration crisis, educating others, and (most importantly) voting for a candidate that will advocate for immigrants.