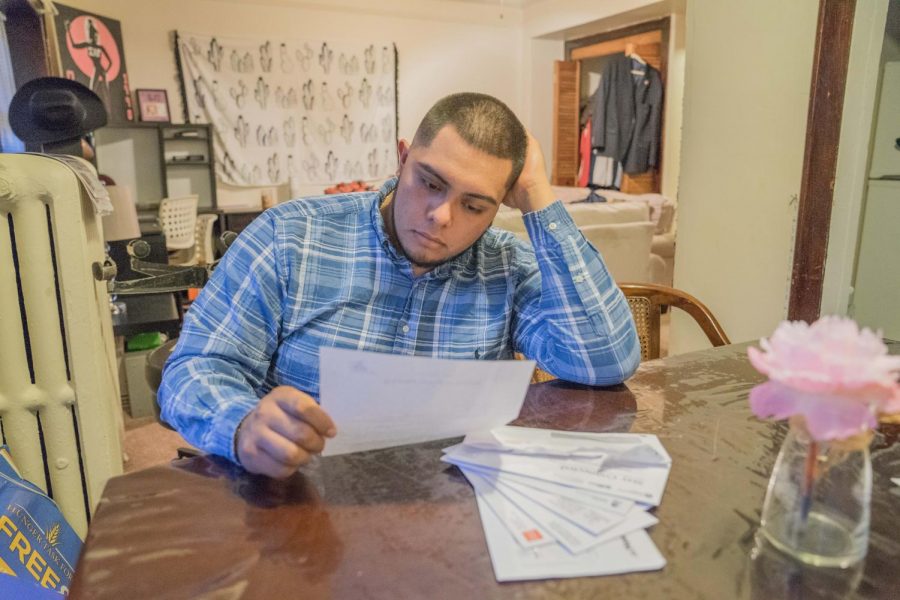

For Alfonso Martinez, it’s hard to even sit in a classroom without thinking about money.

Martinez, a junior in the College of Business Administration, was a freshman when his parents got divorced. On top of the transition from his home in Milwaukee to an on-campus dorm, he found himself dealing with another obstacle: paying his own way through college.

“Being able to support myself and support my education was a very hard task,” he says.

He worked as a cook, a membership analyst, a teen program leader and a Badger Boys State counselor just to stay financially stable.

Now, Martinez is the chairman of Marquette University Student Government’s Diversity, Equity and Social Justice Committee, and works in the Milwaukee Public School system as a mentor and workshop coordinator for high school students. He says his dream job is some form of social work, but it’s difficult to find the financial support for it.

“You only have so many hours in a day, and having to devote that time to working takes a lot of time away from … the things that can really help you in your career,” he says.

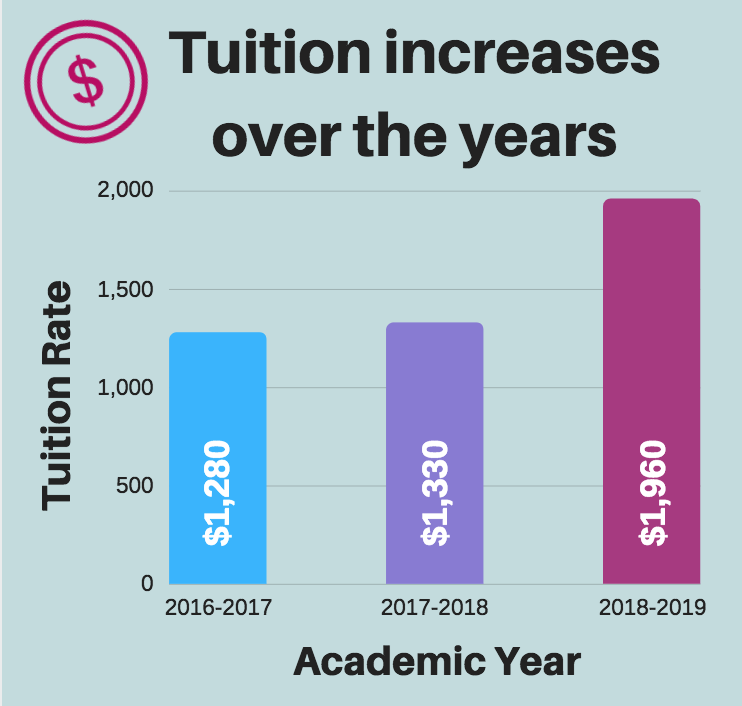

Every year, Martinez has to save up for food, books, miscellaneous school products and tuition. When the Board of Trustees approved a $2,060 tuition increase to be implemented in the 2019-’20 school year, he says it came as a surprise.

“I didn’t see it as a possibility,” he says. “I thought Marquette would be more (financially) stable.”

Acting Provost Kimo Ah Yun explains that tuition rates are set by the Board of Trustees after considering certain costs. The costs include benefits for faculty and staff, student scholarships in the form of tuition discounts, support services like technology, public safety and residence life and various administrative expenses like insurance.

The reason for the tuition increase wasn’t clear to Martinez, and says he didn’t budget for it. Although his two jobs at MPS and MUSG have taken up most of his time, the tuition increase has forced Martinez to look for another.

“With rent and everything … I’m not up to par with what I need,” he says. “Two grand is almost unattainable. It also doesn’t account for the things that can go wrong,” Martinez says, referring to potential health emergencies due to unforeseen circumstances or the loss of a job.

Martinez isn’t alone. A petition to freeze tuition for students currently enrolled at Marquette racked up more than 2,000 signatures in 2018. Although it has since stalled, a Facebook group started by Timothy Gomez, a junior in the College of Arts & Sciences, advocates for a similar goal.

When Gomez started his Facebook group, he sent it to about 30 of his friends via email. He says he was “a little” shocked when it jumped up to 112 members. The page includes memes and graphics representing Marquette’s tuition rates over the years.

“Instead of just having a bunch of people grumbling, you can have one group working together trying to solve the problem,” he says.

Gomez says he believes the group is beneficial to facilitate conversation. Additionally, if he ever schedules a meeting with administrators like President Lovell to address his concerns over the tuition increase, he says he feels more confident in large numbers.

“I think it gives you more legitimacy because if a few people go in there, it doesn’t really matter,” Gomez says.

What he and Martinez both want to know, they say, is where the money from the tuition increase is ultimately going.

Daniel Brophy, executive vice president of MUSG and a senior in the College of Arts & Sciences, says he expected students to be confused about the increase.

“It’s just like, if you were being charged $10 more for a haircut, you would want to know why you were being charged that extra $10,” he says.

Brophy says petitions aren’t particularly effective because he doesn’t see the possibility of Marquette completely freezing tuition. He says petitions do, however, help identify some problems students have about tuition.

“The idea that I kind of got was a lot of students want transparency on this,” Brophy says.

The desire for transparency is what led Brophy to organize a meeting with several key executives from the Budget Office. Jay Kutka, university budget director, is one of the administrators who gave a talk to MUSG Senate in 2018 about the tuition increase.

Kutka says Marquette gets the majority of its money from tuition and fees. Tuition and fees accounted for 61.4% of total revenue from the 2018-19 fiscal year. Room and board was 11.4%. Those numbers alone, Kutka says, prove how dependent Marquette is on its students.

“You can try to change (how dependent Marquette is on tuition) … but it would be hard,” Kutka says.

Ah Yun says he understands what a significant sacrifice college is for students and families.

“Knowing the financial burden that higher education places on many of our students and their families, we cannot rely on tuition increases to pursue our ambitious plans,” he writes in an email. The plans were not specified.

Ah Yun includes a link in his email that leads to a Marquette website which includes graph representations of tuition breakdowns.

According to the website, 47% of tuition dollars are used for faculty and staff compensation, 26% is used for student scholarships and 16% is used for student support. The other 11% goes toward facility and administrative services.

The site’s last update was from 2017, but university spokesperson Chris Stolarski says it always references one solid fiscal year behind. It won’t be updated until later this fall when the Board of Trustees announces new tuition rates.

“The tuition breakdown seldom changes much, if at all. If anything, a few categories may move by a cent or two on the dollar. Though it’s older, it’s still a fair representation of an average tuition dollar breakdown,” he writes in an email.

The university makes some difficult decisions to keep its cost structure in line, Kutka says.

To manage costs and efficiencies, Marquette recently chose not to fill 49 current and future employee vacancies, and it laid off 24 staff members across the administrative, academic and athletics departments of the campus.

The goal, according to University President Michael Lovell’s Sept. 5 letter to faculty and staff, is to ensure the institution remains financially stable. He cites rising tuition as a factor for the decision.

Ultimately, Kutka says, tuition increases are for the benefit of the students.

“Marquette is very diligent about where they’re putting the resources to keep Marquette viable,” Kutka says.

Kutka says the money students are paying the university isn’t going toward frivolous causes. He cites the occupational therapy and physician assistant programs as areas of particular focus.

“Those are all good things for Marquette’s survival because that’s where the need is growing,” he says. “I think we’re being proactive in that.”

Marquette is also building new online courses, Kutka says. David Cheval was recently hired to expand the Marquette University online program.

He also says Marquette is fundraising specifically for increased scholarships and financial aid.

Brophy says that due to the complex nature of Marquette’s hierarchies, students who are not in leadership positions may not have the opportunity to meet with administrators.

“There’s this general information and communication barrier between students and the university, and I think that has always existed,” Brophy says.

To bridge the gap between students and administrators, Kutka and Brophy say they both hope to orchestrate another presentation, similar to Kukta’s presentation about the tuition increase last January, that will be open to the general community, Brophy says.

In the meantime, Brophy says he encourages students with questions about tuition to approach MUSG. While they play no role in decreasing tuition, he says they do want to hear any concerns that may arise in hopes to bring it to the administration.

“We don’t want students thinking ill or thinking badly of university administrators just because there’s a bad communication or miscommunication there,” he says.

Ah Yun says he stresses the university takes matters of affordability seriously and recognizes it is not just a Marquette-specific problem.

According to the Commonfund Higher Education Price Index, inflation for U.S. colleges and universities is forecasted to rise 2.6% in fiscal year 2019. Projected inflation for salaries alone is 2%. The U.S. annual inflation rate is 1.6%.

Educational institutions in Wisconsin are tackling the issue of national tuition rises in different ways.

Carthage College, a private liberal arts school in Kenosha with a student population of 2,800, announced it will decrease its sticker price by $13,000 for the 2020-’21 academic year. Brandon Rook, director of public relations, says the school arrived at the decision after an administrative task reviewed a Sallie Mae study that reviewed how students and parents pay for college.

“Given this research, the effect of the new Carthage model will be to help more families see that Carthage is more affordable than they would have thought,” Rook says.

The Carthage College change may also be purely cosmetic, Kutka says.

“I don’t know if the net benefit for the student is going to change,” he says.

According to the Carthage website, families can expect to pay the same net price as they would have before the tuition slash. Essentially, the move decreases the sticker price of the school, not what students have been paying all along.

Gomez says he isn’t expecting a drastic tuition slash but is hoping his Facebook group tests the waters for small-scale reforms like book vouchers and streamlined communication. He says he suggests sending a school-wide email outlining what money is used for.

“People do struggle a lot, and people’s families are struggling to send them here,” Gomez says.

Martinez says the burden of funding his own college education has taken a mental and physical toll. Going to parties and grabbing dinner are luxurious Martinez says he can’t afford.

“There are a lot of times where you wish you didn’t have the financial trouble that you do because you could do so much more,” he says. “I don’t see it as a healthy thing.”

Martinez is currently working on a financial literacy event with Diversity, Equity and Social Justice Committee and Chase Bank. He says he plans on teaching how to navigate loans, mortgages and credit.

“Instead of viewing (financial insecurity) as a preexisting condition, I saw an opportunity to change it,” he says.

Ultimately, Martinez says he views his time in college — and his financial struggles — as a stepping stone. He says knows he’ll be able to help people like himself in the future.

“I think the mindset that I have has really pushed me through,” he says. “I’m sacrificing myself for the person I will become tomorrow.”