Physical and mental well-being are often intertwined. At Marquette University, the value of “cura personalis,” or “care for the whole person,” emphasizes this notion.

Wisconsin had 64 reported cases of human trafficking in 2018, according to a BedBible report. With a little over 5,000 cases across 52 states, the 2018 national average per state was about 99 cases.

Not every case is reported, but each one takes both an emotional and physical toll on those affected.

Kim Hernandez, a lecturer in history and comparative ethnic studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, teaches a class on the commodification of women, or the process of treating women as objects to be bought and sold. One of the methods of commodification is human trafficking. She said the recovery process involves responding to both physical and mental health.

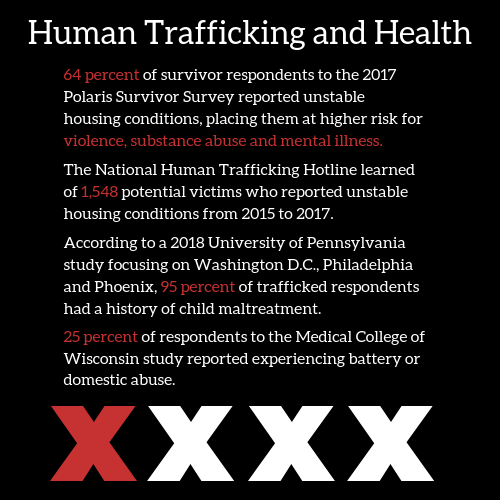

“For some (survivors), they have not just possible physical ailments or effects of being trafficked, but they may have mental health issues,” Hernandez said. “They may have post-traumatic stress syndrome. They maybe developed addiction or alcoholism as one of the means to cope with their situation.”

The background of a survivor can contribute to trafficking susceptibility, Hernandez added.

“People who’ve experienced trauma in their own homes growing up are more likely to be vulnerable to traffickers as they get older,” Hernandez said.

Mindfulness is vital when it comes to treating survivors with a history of physical abuse, as such backgrounds often correlate with human trafficking.

According to a report by the Medical College of Wisconsin and Milwaukee Police Department, 25 percent of people involved in the process of reporting trafficking had previously reported battery to MPD, and 25 percent of people who were believed or confirmed to having been trafficked had reported domestic abuse.

“(Human trafficking) is linked to the lack of opportunity, and it’s linked to some of the things that come with that, including the kind of family dynamics and violence that can take place as a result,” Hernandez said. “Then it can become a cycle where children grow up in a household where … their parents were already affected, and this would then lead to increased vulnerability for this new generation.”

The stigma regarding human trafficking can further complicate the recovery process.

“It can be so stigmatizing especially if it happens to, say a middle-class family that you wouldn’t expect this kind of thing to happen to,” Hernandez said. “Another part of it that’s stigmatizing is … the fact that (trafficking can be) within a private home, a private household. There’s then an element that then might cause people to feel culpable in some way.”

Though it may not be obvious to the average person, human trafficking is prevalent in the community surrounding Marquette.

From 2013-’16, 340 individuals in Milwaukee were believed or confirmed to have been sex trafficked, according to the report by the MCW and MPD. Of the cases reported, 97 percent of people trafficked were women.

Through a 2011 partnership with MPD and the Milwaukee County district attorney’s office, female survivors of trafficking can take part in the Sisters Program at the Benedict Center. The center resides in the Halyard Park neighborhood on N. Doctor M.L.K. Jr. Drive in Milwaukee.

According to the organization’s website, the Sisters Program is meant to help women rebuild their lives post-trafficking by providing resources, a safe place to stay and a supportive community.

Jeanne Geraci, executive director of the Benedict Center, said the program focuses on women because they are the most targeted demographic of street-based sex trafficking. However, she said the program will help anyone who needs it.

“We don’t want to discriminate between who is deserving and undeserving of help,” Geraci said.

The center also provides counseling in one-on-one settings and in support groups. Geraci said it is crucial to have individuals to help who are educated on trafficking and its effects. The Benedict Center staff is comprised of trained advocates, with some of the women who go through the program remaining involved to provide guidance to new members.

One of the program’s primary missions is to promote an alternative method of following up with survivors of human trafficking.

“We can’t arrest our way out of the problem,” Geraci said.

She added incarceration of survivors is too often society’s first response.

She said she was pleasantly surprised when MPD reached out to offer a partnership. The center has been expanding its network of partners ever since.

Geraci emphasized the importance of the center’s collaboration with other organizations. According to the center’s website, some of its other partners include the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee County Housing Division and the School Sisters of St. Francis.

In January 2018, the MCW and the Benedict Center received a nearly $350,000 grant for their project called Access to Safe Shelter & Housing for Women in Street-based Sex Work. The 36-month project aims to make access to housing easier for survivors of trafficking because the “inability to access safe housing and shelter increases risk for exposure to poor health and outcomes such as violence and victimization, substance abuse and mental illness.”

“Many people do not realize that women in the street based sex trade are homeless,” Geraci said in an email. “Women identify housing as a priority.”

The first step toward helping survivors recover mentally from trauma is for society to change its mind, Geraci added.

“Many women in the street-based sex trade are stigmatized and criminalized,” Geraci said in an email. “We need to replace oversimplified narratives with the understanding that each individual has a story and, rather than judging or rescuing, we need to seek to understand and treat each person with dignity and respect.”

The background of each survivor is complex and important — the same can be said about the distinction between prostitution and sex trafficking.

The Legal Information Institute, a nonprofit organization at Cornell Law School, defined sex trafficking as the occurrence “in which a commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion.” On the other hand, it referred to prostitution as, “the profession of performing sexual acts for money.”

Geraci said she recognizes the importance of this distinction.

“There are different reasons women are in the street-based sex trade,” Geraci said in an email. “Some women are trafficked, others are there for other circumstances. Rather than criminalizing women or determining who is a deserving … survivor … let’s offer support to women regardless.”

In a 2013 report, Covenant House New York, a youth homelessness shelter in New York City, conducted interviews with 174 randomly sampled youths in the shelter’s crisis center and drop-in programs. The report was conducted with assistance from Fordham University. Twelve percent of the subjects were trafficked for sexual exploitation. Of that 12 percent, 36 percent were trafficked by their immediate families and 27 percent were trafficked by boyfriends.

“Young women … end up being pulled into trafficking through a relationship that they make with somebody that they believe, (or) they come to believe, cares for them and loves them,” Hernandez said.

While trafficking can have damaging effects on personal relationships, physical injuries can also be long-lasting.

Angela Rabbitt, a specialist in pediatrics and child advocacy protection services at the MCW and Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, said there are important guidelines for the medical care of youth who have been trafficked.

“It’s really important (for) youth who are trafficked … to have a standardized response so providers know what to do,” Rabbitt said. “(Children’s Hospital has) a written protocol that helps providers understand risk factors so they can do appropriate screening.”

The physical injuries that result from trafficking are often violence related, Rabbitt added.

“We see a lot of violence related injuries … (much) like injuries related to sexual assault,” Rabbitt said. “We also see youth who come in with injuries from being beaten by their trafficker.”

Rabbitt said she often sees trafficked youth having high rates of sexually transmitted infections. She also said she sees evidence of self-harm, such as cutting behaviors or suicide attempts, on these patients.

Rabbitt said staff is trained to ask questions “in a non-leading way about abuse” and to have multiple treatment options — interviewing, medical services, mental health consultation and child advocacy services — accessible to survivors in one place. She said this accessibility is a key aspect of the recovery process.

The convergence of the various services is important due to the connection between physical and mental well-being, Rabbit said.

“If you look at adults who have been victimized by trafficking, when they’re coming in for medical care, their biggest complaints are chronic pain … and also mental health and addiction recovery services because of the psychological trauma they experienced during their victimization,” Rabbitt said.

Geraci added organizations aiming to support sex trafficking victims should make sure women with lived experience are part of their leadership.

“Let’s change systems so that women have real options to live full, healthy, and happy lives,” Geraci said in an email.

This story is part of the Blind Spot series on human trafficking in Milwaukee that launched in the spring issue of the Marquette Journal.