In fall 2017, a group of Democrats from Wisconsin took a case to the U.S. Supreme Court accusing the Republican-controlled state legislature of gerrymandering. The case Gill v. Whitford was sent back to the lower court in a unanimous decision, allowing the state legislature to continue current practices. The case will likely return to the Supreme Court in the future, but until then, the 2011 redistricting will continue to influence party representation for years to come.

Every 10 years, states are legally required to redraw all federal and state voting districts. State legislatures are expected to delegate the duties of redistricting either to themselves or to a nonpartisan commission. A majority of state legislatures choose to handle the redistricting themselves. Wisconsin is one of those states, and it is not the first to be accused of gerrymandering.

As political science assistant professor Philip Rocco puts it, “Gerrymandering is kind of as old as the United States.”

Gerrymandering is the process of redrawing legislative districts in ways that give the majority party an advantage over its opponent. There is a check against this: a state’s governor has the right to veto the proposed map and force a legislature to redraw until the districts are more balanced. However, when a party has a trifecta — control of the state Senate, Assembly and governor’s mansion — this reduces the chance that a governor will reject an unfair map. In 2010, Republicans won a trifecta in Wisconsin.

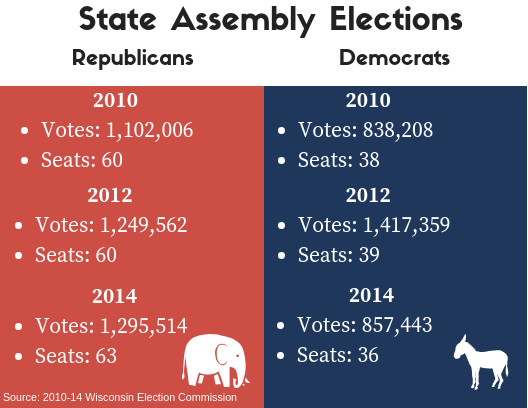

A common practice in gerrymandering is a process referred to as “packing and cracking.” Packing describes the placement of a minority party’s voters into single-party strongholds, meaning certain seats for the minority party will become near-invulnerable. Cracking is the consequence of packing: little to no representation for the minority party in most districts, cracking the minority party’s power. In 2012, Wisconsin Democrats received 174,000 more votes statewide than Republicans, but the Republicans had a 21-seat majority in the State Assembly that year.

Advanced technology has increased a legislature’s ability to pack and crack effectively. The development of geography-based data tools has given state legislatures access to maps showing both the racial and partisan makeup of an area.

“We now know with a high level of precision where voters that prefer a particular party live,” Rocco said. “That has made it very possible for not only state legislatures to gerrymander, but to gerrymander in a way that they can guarantee that (the gerrymander) is going to be very hard to overturn.”

Evan Goyke represents Wisconsin’s 18th District in the State Assembly, part of Marquette’s campus. As a Democrat in urban Milwaukee, he’s running unopposed this November.

One of the ways to prevent gerrymandering regardless of trifectas is to give the responsibility of redistricting to a nonpartisan commission. However, this decision would have to run through a likely reluctant state legislature.

“You might imagine that you’re the party in power in a state legislature, or you are a party that’s not in power, but you might be at some point in the future … creating an independent voting commission is a way of delivering power to your opponents,” Rocco said.

Most states with nonpartisan commissions went directly through the ballot rather than the legislature for this reason. In western states like California, there are direct methods for constituents to get initiatives like this on the ballot because their constitution allows them direct powers of referendum through signatures. Wisconsin, however, is one of 24 states that does not allow initiatives or referendums. The only path for Wisconsin residents to get issues like this on the ballot is through the State Assembly.

Goyke said he would rather see it handled by an independent commission, regardless of the political consequences. He describes how Gill v. Whitford sought to include partisan makeup in a pre-existing list of unconstitutional factors in redistricting under the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause.

“Adding partisanship to that list of protected or out-of-bounds or off-limits categories is good,” Goyke said. “That means even if we retain partisan redistricting, nobody can cheat so bad, but it would be better to just get it out of our hands altogether.”

Rocco, on the other hand, is not sure the case will be tried again with the 14th Amendment. Due to the level of explicit proof that the 14th Amendment requires, Rocco says he thinks the plaintiffs might reconsider using the right to assembly protected by the First Amendment.

“Rather than arguing as me, individual voter, who’s a Democrat who lives in a gerrymandered district, (they are) arguing the case as a party — or highly motivated members of a party — whose ability to ensure that that party can be politically competitive and effective is preserved,” Rocco said.

Goyke did not mince words when describing how this has affected the Assembly.

“We’re segregated,” Goyke said. “We don’t talk to one another.”

Goyke said his district, which is roughly 80 percent Democratic, shares a border with the 13th Congressional District, which is roughly 70 percent Republican. Despite sharing a border, Goyke says that the representation required for those two districts is completely different and is also decided by the end of the primary elections.

“When your district is closer to 50-50, you have to pay attention to a more diverse set of voters’ voices, needs and that then translates into more bipartisanship and more effective collaboration across the aisle,” Goyke said. “There’s almost a disincentive under the current political map in the Assembly for either a Democrat or a Republican to work across the aisle.”

Goyke said that if more districts included a mix of urban and suburban constituents, the Assembly could try to overcome what he described as an “us and them” mentality.

“Elected officials’ prerogative on policy has to be a little wider,” Goyke said. “For example, instead of school funding for MPS at the cost of Wauwatosa, it would then force a dialogue and a policy solution that would seek more equity.”

Democratic Rep. Greta Neubauer of the 66th Assembly District said gerrymandering on both sides decreases the democratic process. The 66th District was mentioned in Gill v. Whitford as an example of packing and cracking. Neubauer has never had a Republican opponent.

“I think that’s a shame,” Neubauer said. “I would like to debate these ideas. I think the people in my district deserve to have different ideas presented and represented by the candidates running for office in their district.”

Neubauer also said she supports an independent voter commission.

“People deserve to choose their elected officials, not the other way around,” Neubauer said.

Neubauer said because the Republican majority is so overwhelming, it is preventing the Assembly from having conversations that will affect Wisconsinites. She said that common sense gun safety laws, for example, were not discussed adequately in this year’s session.

For now, Republicans will let the courts decide the merits of their 2011 map.

Mark Radcliffe, a legislative assistant for Republican Rep. Rick Gundrum of the 58th Assembly District, said in an email: “With the merits of the current legislative districts still being deliberated in the court system (namely, through Gill v. Whitford), Rep. Gundrum believes the courts will serve as the channel through which many of the current questions surrounding legislative districting plans are resolved.”

Unless it is struck down in the courts, the legislative map will not be changed until the 2020 census.

Richard Zimermann • Oct 31, 2018 at 1:11 pm

“[State legislature] gerrymandering is kind of as old as the United States.” — so it is not surprising that there have been efforts to correct for it in the Congress — just as Madison’s Federalist Papers envisioned the national legislature as a corrective to narrow state “faction” interests and overreach. Congress previously required both “contiguous” (1842) and then “compact” (1872) Congressional districts. In Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004), the Supreme Court confirmed Congressional Art. 1, Sec. 4 authority “to regulate federal elections to restrain the practice [of state legislature gerrymandering]”.

If Congress amended the U.S. Code to restore those requirements, and added, “to the greatest extent possible, follow city and county boundaries.”, — that could establish “justiciable” grounds for local suits against partisan gerrymandering by state legislatures. Note their pedigree: Jacksonian Democratic (1842) and Lincolnian Republican (1872). Maybe it could be something for the next Congress in time for the 2021 state redistricting.