Since big-name film producer Harvey Weinstein was accused of sexual assault Oct. 5, more than 20 men in similar powerful positions have faced accusations — and the list keeps growing daily even as this article is being written.

All 22 of those men, including Weinstein, have either been fired or have resigned from their respective positions and companies.

Some of the accusations date back decades, even some coming from women who have been out the business for several years. It leaves an underlying questions on the minds of many: Why now?

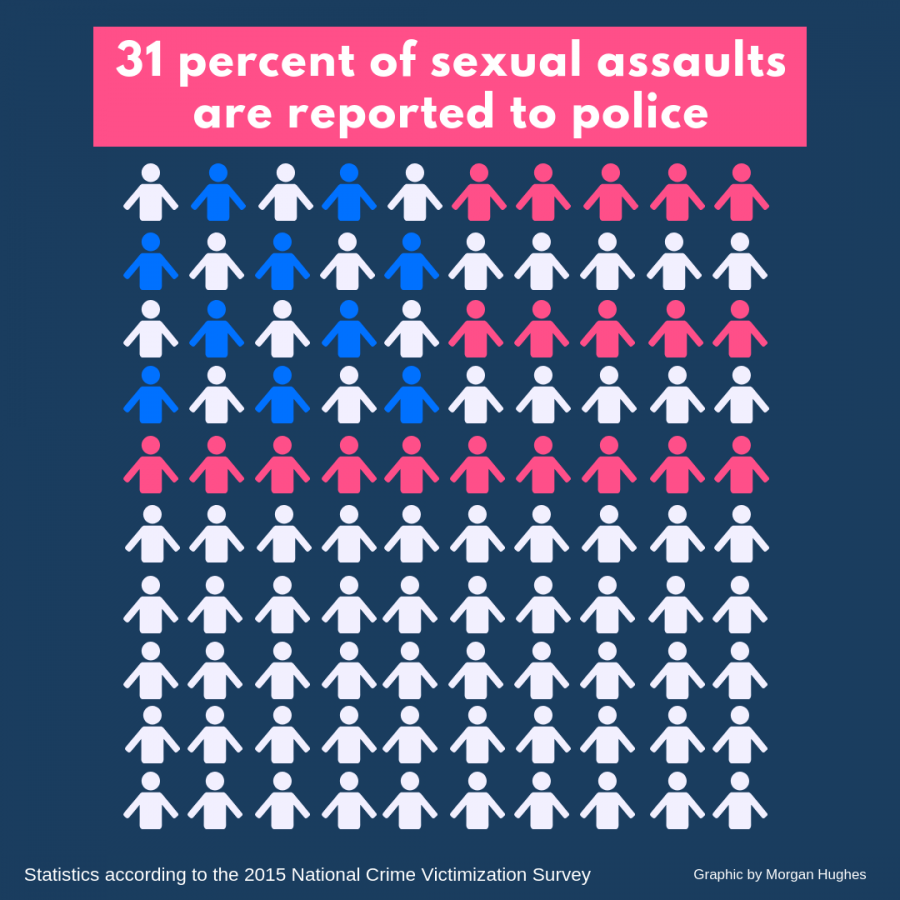

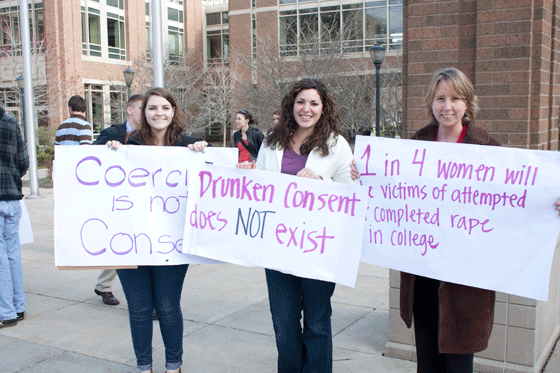

The answers as to why women don’t report sexual assault have been tossed around and are pretty well known: Rape culture, a fear of facing prejudice and a fear of not being believed. But the answer to why Oct. 2017 was a tipping point is more complex.

Title 18 of the U.S. federal code, written in 1986 by the 99th congress, explicitly makes illegal any forced sexual contact. Additionally, states have their own laws that may be harsher than federal laws. That law has been there, certainly seemingly in place to protect victims, so why are they only now being widely utilized?

“The law is really important, and I used to think it was the only important thing, but it became clear there was much more to it in an underlying cultural sense,” Cheryl Maranto, an associate professor in the College of Business Administration who researches gender discrimination and labor relations in the workplace, said.

“Women not only fear social repercussions, but those that come in their professional careers as well,” Maranto said. “They have to make a choice between living with it or potentially ending their careers … these men can make or break their professional opportunities.”

Enough time has passed that many of the men who have been accused no longer hold as much power as they used to, Maranto said. Additionally, women have been gaining positions of leadership over time, so victims aren’t facing as much of a male dominated system.

Maranto said victims may feel more comfortable coming forward now that the men don’t have that power over them. Additionally, they may have a position where they themselves have established power and their claims would be taken legitimately.

Besides ending careers, “Men often have the power to financially ruin a woman through lawsuits as well,” Maranto said. “Once that woman is out of that environment, it makes it easier to report, so it’s not just a matter of reporting to the police, they feel they have to wait until their careers aren’t at risk.”

But once a victim no longer has to work with or around their abuser, it may make it easier for them to disclose, said Katy Adler, a victim advocate with the Counseling Center.

“Once they don’t have to see them often, or live in the area, it can make the victim willing to come forward,” Adler said. “We get a lot of students (at the Counseling Center) who are only disclosing once they get to school here.”

Another contributing factor may be that victims didn’t know what was considered sexual assault or harassment at the time, and it took years for them to come to the realization and be given the information to clarify that. For many young women in the industry, that was just part of business.

Also, many of the acts of victimization committed may not have been considered crimes or inappropriate societally at the time. Adler said victims are much less likely to report when they know the assailant, which is the case of many accusers in the recent storm.

“It is my perception that the survivors who were assaulted by strangers are the ones that are most likely to report … so that is a large contributor to why some people may not report, and if they do it takes them a while,” Adler said.

Additionally, the resources for victims have been steadily growing for decades. At the time of the incident, PR departments and police forces didn’t have the special training they do today.

“They may not have had access to counseling,” Adler said. “Not everywhere has the type of support systems as we do at Marquette.”

Meghan Stroshine, an associate professor in the social and cultural sciences department, focuses her research on domestic violence, women and crime. She said that, parallel to her research on domestic abuse, it may take seeing an abuser actually face consequences before more victims are willing to come forward.

“Many victims don’t see themselves as victims, they are embarrassed and they fear judgment,” Stroshine said. “This fear of judgment and potential repercussions fuels a lot of the decision not to report … in the recently highly publicized cases.”

Stroshine suggested that teaching about sexual assault in school and publicizing the information helps combat the culture of non-reporting.

“Social support is mixed, and there is conflict and confusion as to how and where to report,” Stroshine said. “Making the process clear will bring forward victims, and eliminating the idea that it’s personal issue that should be dealt with personally, or that nothing would be done.”

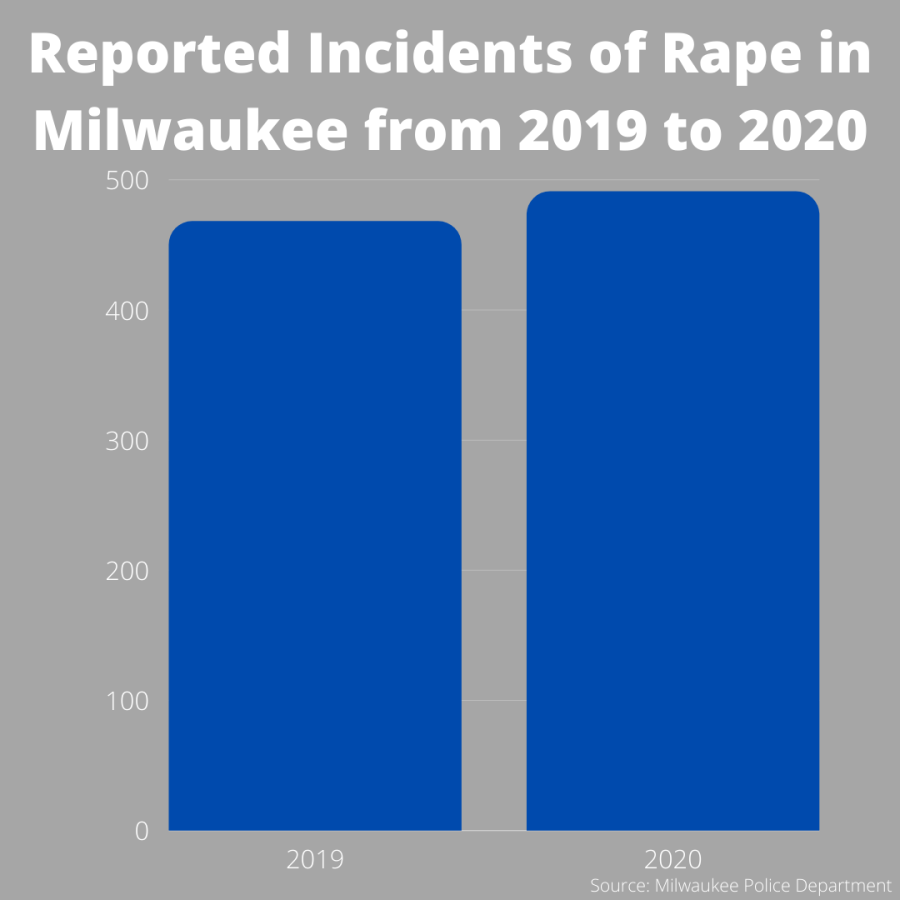

Stroshine said all of the recent accusations hopefully help to open people’s eyes to the extent of the problem, “Part of this culture is minimizing what happens to victims, and this list of highly public accusations certainly isn’t minimal.”

Maranto said it has taken a large scale, albeit slow, societal shift has made victims more comfortable coming forward. She said she is hopeful for the future, and she thinks this is a point in time that represents a shift.

Society seems to be at an interesting divergence point, where the recent political climate has prompted strong women movements, according to Maranto. Additionally, she said a significant amount of the rhetoric being tossed around in the political sphere may drive victims to the point they feel a responsibility to come forward because “words have the power to incite anger.”

“When one woman comes forward, the snowball effect has the power to take hold,” she said. “When they see other victims coming forward, and being believed, and see the men on that growing list facing real consequences, it’s empowering.”