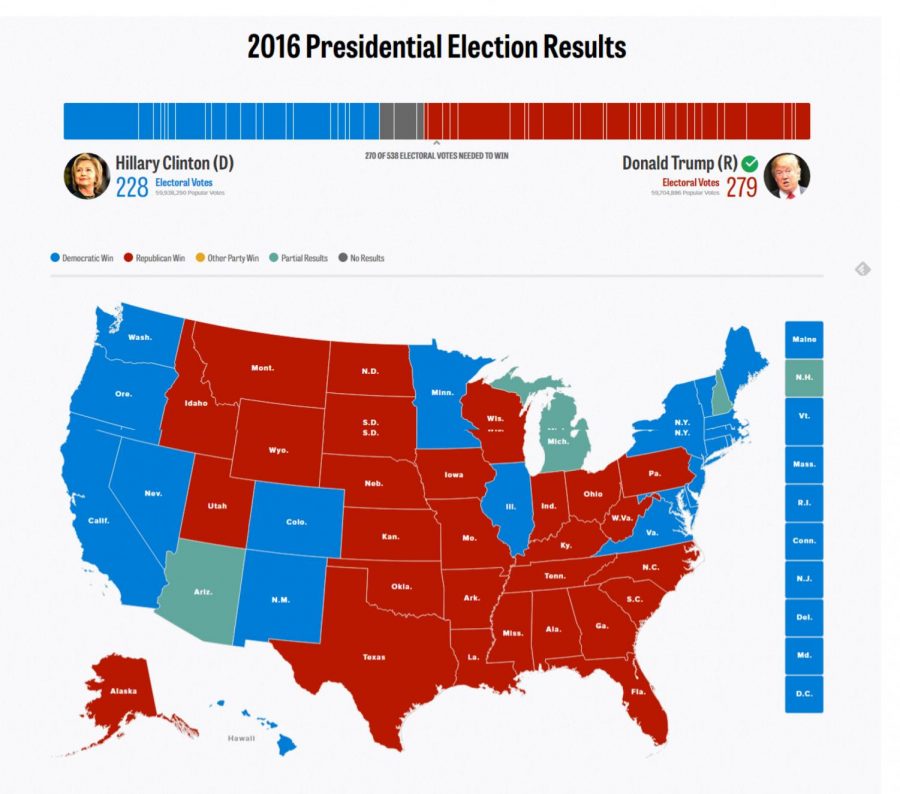

The 2016 election was a stark reminder that our electoral process is broken. The winner of the electoral college has lost the popular vote and ascended to the presidency four times in American history. Voter turnout in the most consequential election in decades was only 58.8 percent, and many were displeased with the two choices our party system presented us with.

Many people consider these problems a consequence of the electoral college, especially after this past election. However, although that system is also undemocratic, many of these problems are largely due to the archaic process in which we elect our representatives. Nearly every election in the United States uses a first-past-the-post (FPTP) winner-take-all system. Under FPTP, the winner of the plurality of the vote is the sole winner of an election.

FPTP is one of the reasons turnout is so low. In my home state of Maryland, it is extremely difficult for a Republican to win a statewide race. The current Republican governor, Larry Hogan, is more moderate than most Maryland republicans. The less moderate Republicans are not well-represented because the winner-take-all system forces a strategic nomination of the least conservative Republican to avoid losing to a Democrat. As a result, many voters do not show up to support a candidate they’re unenthusiastic about, or one who they think has little chance of winning. It does not have to be this way.

In November, Maine narrowly affirmed Question 5, a ballot measure establishing ranked-choice voting in statewide elections. Ranked-choice is simple: instead of choosing one candidate, voters rank the candidates in preferential order. The candidates with the least support are eliminated and the votes cast for them transfer to each voter’s second choice candidate. This continues until a candidate has a majority, not a plurality, of the vote. So why should we switch to this system?

First of all, it removes the “spoiler effect,” one of the largest deterrents from voting for a third-party candidate. Didn’t like Trump or Clinton? With ranked-choice voting, you could have voted for someone who more accurately reflected your views without having to worry about electing the greater of two evils. Essentially, the necessity of strategic voting disappears.

It also forces candidates to receive a mandate in order to achieve office. For instance, under FPTP, Candidate A receives 30 percent of the vote, Candidate B receives 28 percent and Candidate C receives 42 percent. Even though 58 percent of the people voted for a different candidate, C is still the winner. What’s worse, the majority of B voters say that A was their second choice.

If this same election were to happen with ranked-choice, Candidate B would be eliminated and his or her votes would transfer to the voters’ second choice. This ensures that the winning candidate has more support than opposition.

If ranked-choice voting is paired with multi-member districts instead of the single-member legislative districts we currently have, it can eliminate gerrymandering, the process of manipulating district boundaries to benefit one party over another. More seats in larger districts means more candidates, greater choice and more accurate representation of a district’s voters.

A more representative government benefits everyone: Republican, Democrat, Libertarian or Green. Higher citizen turnout and satisfaction offers legislators more freedom to collaborate outside of their parties. If the last eight years have shown us anything, they have shown that hostile partisanship clogs the gears of the legislature.

I think the reason liberals were so upset about the 2016 election had less to do with the fact that Trump won, and more to do with the mechanics of his victory. His margin of victory was so small (less than 100,000 votes in three states) that it is hard for some to imagine that Stein and Johnson voters would not have preferred Clinton (although this is simply unprovable).

In the short term, ranked-choice is not feasible at the federal level. It would require a constitutional amendment with two-thirds ratification from the states. However, Maine’s leadership is a step in the right direction. If we want to increase engagement, satisfaction and turnout in our elections, we must implement ranked-choice at the state level.