This year, the Marquette Law School poll generated 360 national media stories in four months, according to a study conducted by the university.

The poll was not created solely for election updates, but instead was originally used to gather public opinion on civic issues in Wisconsin.

“At the time we were talking about this, I did not appreciate just how massive politics would loom in this,” poll director Charles Franklin said.

Franklin thought urban, rural and religious life would be topics of discussion. He and law school fellow Mike Gousha began talking about developing the law school’s public policy program.

Gousha hosted an “On the Issues” conversation series where political experts came to the law school and spoke about public policy, while Franklin wanted to see more of the public’s opinion represented. The two discussed creating a poll.

“I’m either one of those idealistic or naive people that believe polling serves an important civic purpose of giving a forum where a representative sample of the public gets to have their say,” Franklin said.

Gousha and Franklin brought the idea to the dean of the law school, Joseph Kearney, who was not immediately convinced.

“When I first heard about (the law school’s) interest in public polling, I did not understand what a public good such a survey could be,” Kearney said. “It took some explanation.”

Franklin, Gousha and other faculty explained that the poll would cover more than the “political horse race.” In addition to election coverage, it would examine public policy and support faculty research, and provide an accurate depiction of public views.

“We should not simply assume that we can know simply from people’s partisan identifications what all of their views will be on every topic,” Kearney said.

Some of the social issues the poll has analyzed include economic inequality, education and water quality.

After a year of internal discussion, in 2012 Marquette University Law School created the poll. Kearney described the timing as “exactly right” because it was not only a presidential election year, but there was also a governor recall election between Gov. Scott Walker and Mayor Tom Barrett.

During its first year, the poll generated more than 650 local and national media stories, including television coverage reaching a total of 10.6 million viewers.

Although the poll became a trusted source among the media, there were times it was criticized by both parties.

“Any public poll always at least irritates one side,” Franklin said. “That comes with the business and you can’t let that bother you.”

According to Franklin, Democrats heavily criticized the poll in 2012 when it showed Gov. Walker had a lead. In the fall, conservative Republican radio denounced the poll when President Barack Obama and Sen. Tammy Baldwin were predicted to win.

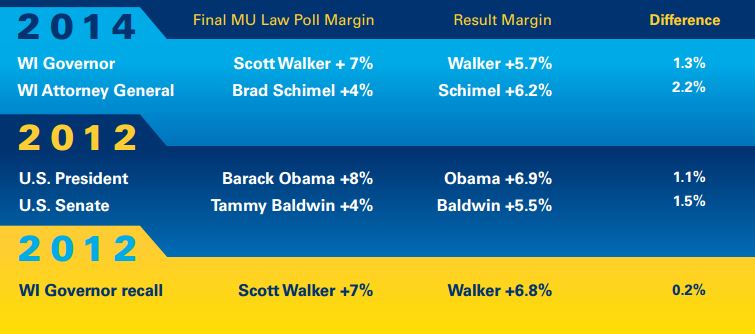

The poll was correct about each winner. “I think it turned out to be a huge blessing,” Franklin said about the criticisms the poll received from both parties. “We were right when a Democrat was winning and when a Republican was winning.”

By the end of 2012, Kearney was left with one question: “At the end of that year we had an extraordinary run and we had one question: Should we continue it?”

Franklin was only supposed to work at Marquette for one year, but Franklin chose to leave the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he was a political science professor, to stay at Marquette.

Associate director of university communication Chris Jenkins said Franklin’s methodology is responsible for the poll’s accuracy. “Professor Franklin is widely known for his accuracy,” Jenkins said. “That comes from his expertise and his commitment to using live interviewers who talk to respondents via randomized calls to both cell phones and landlines.”

Many campaigns run their own polls, but Kearney said constituents deserve the same access to that information.

“(Politicians) have a sense what public opinion is, but the public doesn’t,” Kearney said. “If we ask a question, we release the results. We put it all out there.”

(Prof) Michael Cover, Department of Theology • Nov 16, 2016 at 9:26 am

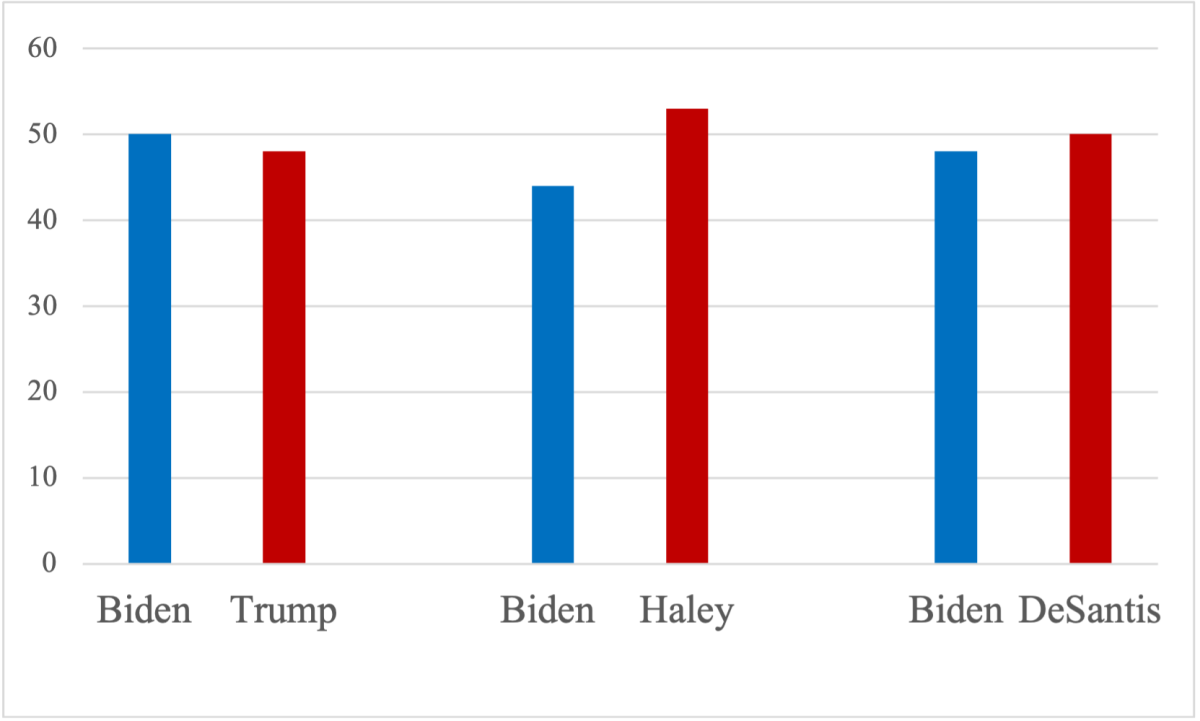

I read with interest Ms. Rebecca Carballo’s article on the history and past performance of the Marquette Law School poll in the November 9, 2016 issue of the Tribune, which was well-written and informative. One did, however, sense that somehow, in the first edition of the Tribune covering Donald Trump’s upset election, the lede had been buried. Ms. Carballo’s article helpfully chronicles the past accuracy of the Marquette Law School poll. This is fine in itself. Neither hers nor any other article, however, clearly and prominently articulated the elephant in the room: that, along with other state-wide polls, the Marquette University Law School poll failed to predict the Trump victory by a wide margin (Clinton was listed as having a comfortable 6% lead). While the law school poll was thus not appreciably less accurate than others on the state and national levels, students and faculty ought to be asking why this year’s poll missed the mark and what might be done to improve polling techniques in future years. Additionally, as New York Times columnist David Brooks noted on the night of the election, the failure of the polls nationwide reinforces what philosophers like Alasdair MacIntyre have been saying for decades: the social sciences have limited predictive power. While Mr. Trump’s election may have been unprecedented in the history of the American presidency, his ascendancy is not “surprising” in the long history of world civilizations; the biblical book of 1-2 Kings, Plato’s Republic, and Tacitus’ Annals provide myriad analogues. In addition to challenging social scientists to refine their methodology, this year’s failure of the pollsters serves as a reminder that our disciplines are indeed complementary—there is no surrogate for the careful study of history, philosophy, and theology.