Among the most contested issues this election season was the issue of raising minimum wage. Proponents, including President Obama, say raising the minimum amount paid to American workers will help low income families make ends meet, lower the level of income inequality and provide struggling businesses with an influx of customers with more spending money. As opposed to the “trickle-down economics” pushed by Republicans, in which the economy is improved through policies that benefit business owners, Democrats and their allies believe a “grounds-up” approach, focusing on the greater majority of the population, would better serve to invigorate the country’s sluggish economic engine.

Issues of values and morality have also come into the debate. President Obama said raising the minimum wage is a matter of preserving the American dream, stating that people who work hard should not have to live in poverty.

“We believe that in America, nobody who works full-time should ever have to raise a family in poverty,” Obama said during a weekly address in October. “And I’m going to keep up this fight until we win. Because America deserves a raise right now. And America should forever be a place where your hard work is rewarded.”

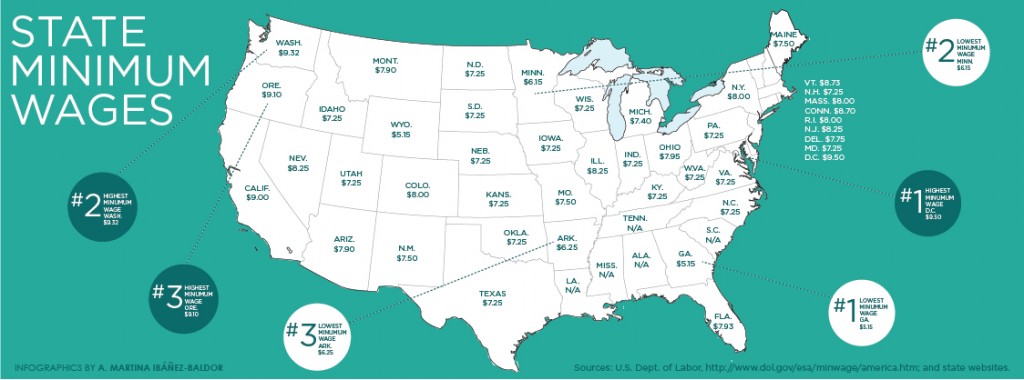

The argument proved to be convincing, as referendums calling for higher minimum wages passed in Alaska, Arkansas, Nebraska and South Dakota, all states that voted against the president in 2012. They will join a number of states that have already decided to raise their minimum wages through legislation.

The current federal minimum wage is $7.25 an hour, with 23 states currently paying workers more than that. Wisconsin’s minimum wage is the same as the federal rate, and makes the same exceptions to the rules. For example, tipped employees including waiters and food delivery drivers, are allowed to be paid a minimum of $2.13 an hour, with the assumption that tips collected will make up the difference. In addition, employees under the age of 20 may be paid $4.25 for the first 90 calendar days, after which they must be paid the normal rate.

At the minimum wage, a full-time worker earns $15,080 per year before taxes, which is above the single-person poverty line of $11,945, but much lower than the standard for a family of four with two children, which is $22,283 per household. President Obama has proposed raising the minimum wage to $10.10, giving full-time workers a salary of $21,008 per year. Seattle became the first American city to raise its minimum wage to $15, and since then, some activists, such as union-backed protesters in Chicago, have used $15 as a benchmark.

Just 4.3 percent of workers in the U.S. are paid at or below minimum wage, but a disproportionately large number of these workers, one-fifth, are between the ages of 16 to 24. In addition, about 27 percent of minimum wage workers are part-time employees. Despite these statistics, a voice that is not heard often in the debate is that of student employees, full-time students who work part-time at on-campus jobs and often earn near or just above minimum wage.

Marquette classifies student employees under five grade levels based on the skills and responsibilities of their job. The first, lowest paying grade level starts at $7.25 and caps at $8.25. This category includes desk receptionists at residence halls and apartments. Cafeteria workers, whose jobs resemble those of fast food workers at the center of the debate, start at $7.75 an hour, which places them on the fourth-highest grade level. The highest grade level, which includes LIMO drivers, starts at $8.20 and peaks at $15. If Obama’s proposal were to pass, student employees would instantly gain a substantial raise. If Milwaukee were to follow Seattle’s model, every student employee would be paid the same as the ‘most qualified’ are today.

According to Associate Director of University Communication Andy Brodzeller, “each college, division and office in the university separately hires for and budgets to pay student employees.” This makes it difficult to tabulate exactly how much the university would have to pay in the event of a raise in minimum wage, especially because some employees, such as cafeteria staff, are paid by subcontractors like Sodexo.

Marquette, however, would not have to front the entirety of these new costs. Under the federal work-study program, Marquette is responsible for paying only 35 percent of a qualifying student employee’s salary, with the rest paid by the federal government. For the academic year of 2013-2014, Marquette received $4,142,907 in work study subsidies. But because the Federal Work Study program is a financial aid program based on need determined by the FAFSA, not every employee can benefit from the program.

For some, raising the minimum wage serves as a countermeasure for rapidly rising tuition costs. But others counter that such an act will only accelerate these costs, since student wages are paid through student tuition. At Ohio University, the student senate passed a resolution calling on the administration to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour. According to The Post, the university’s student newspaper, 47 percent of student jobs at OU are minimum wage positions. The same resolution called on the administration to institute a tuition freeze, but according to Stephen Golding, vice president for finance and administration, the Senate cannot have both. Golding says even a modest 25 percent increase to student pay would “require a tuition increase to cover the cost of the wage increase.”

Here at Marquette, administration officials appear to be ambivalent towards the issue, though some considerations have been made toward it.

“The university’s budget planning process includes forecasting models in a variety of areas, such as benefits, utilities and wages,” Brodzeller said. “These forecasts are regularly updated and allow the university to plan appropriately for increases.”

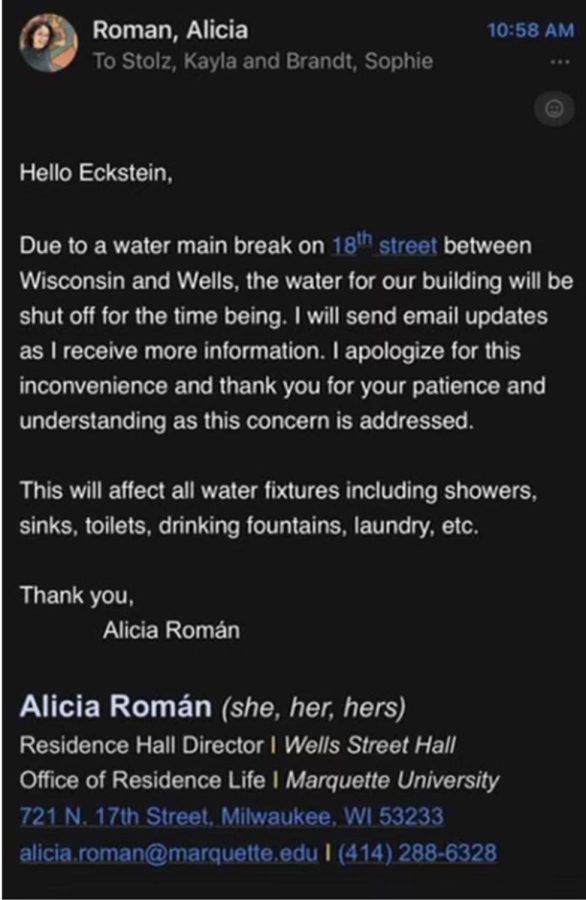

The Office of Residence Life is one of the largest student employers on campus, with hundreds of employees spread across Marquette’s residence halls and apartments. More than 135 of these employees are paid through stipends, as opposed to hourly wages, which means they would not be directly affected by changes to the minimum wage.

According to the university, a stipend is “distinct from wages or salaries because it is not intended to compensate a student for work performed. Rather, it is intended to free up a student to undertake a role in connection with educational studies or research that would normally be uncompensated.” In determining whether a job should be paid through a stipend, the university has established two criteria: “the student’s activities related to the stipend are substantially unsupervised and the hours in which the student performs the services are not easily tracked.”

Interestingly, the university states the amount paid as a stipend should be determined in a “manner to assure that the student receives compensation at or above the applicable minimum wage given a reasonable estimate of the amount of time that the student will dedicate to the activities.” ORL pays resident assistants, facilities/apartment managers and diversity peer educators through stipends. But because of the nature of these positions it is difficult to determine a “reasonable estimate” of how long they work and thus how much they should be paid.

Of ORL’s more than 260 hourly paid employees, Housing and Residence Life director Mary Janz said some cuts would have to be made if costs were to rise.

“If minimum wage increased to $15 per hour we would likely need to make some cuts,” Janz said.

However, Janz also emphasized some student positions deemed essential would not be affected.

“Front desk staff would not be one of the cuts made,” Janz said. “The desk receptionist position is key to greeting residents and their guests along with providing a sense of feeling safety and security to students living in the residence halls and University owned apartment buildings.”

Still, other officials, such as Sodexo’s general manager, Kevin Gilligan, believe it is simply too early to gauge how certain policies may be affected.

“To begin to speculate (on payroll matters) would be irresponsible and careless,” Gilligan said in an email.