The arrival of University President-elect Michael Lovell brings the possibility to reverse a decade-long trend of increasingly costly philanthropy to the school.

“(Lovell) will have the chance to help us understand what the expression of the strategic plan will look like, which will give us our fundraising opportunities,” said Michael VanDerhoef, vice president for university advancement. “I think we’re all interested in launching a new campaign, but we just want to make sure that we’re prepared and that we’ve picked the right priorities for the university.”

Although there is no set timeline for Marquette’s next fundraising campaign, VanDerhoef said he is eager to start the discussion as soon as possible. It certainly will come as a relief to the university, which has not orchestrated a philanthropy campaign since its last one ended in 2006.

Another campaign would also ease the strain on Marquette’s budget, which saw a slowly declining trend in net gain from fundraising efforts between 2003 and 2012, according to numbers collected from the university’s tax records.

However, this trend is not due to Marquette receiving less money from its donors. Instead, net gains are losing steam as a result of the university spending more to fundraise without seeing a substantial boost in returns. Marquette’s fundraising expenditures nearly tripled over the last decade, from $6 million in 2003 to $17.1 million in 2012, the latest data available.

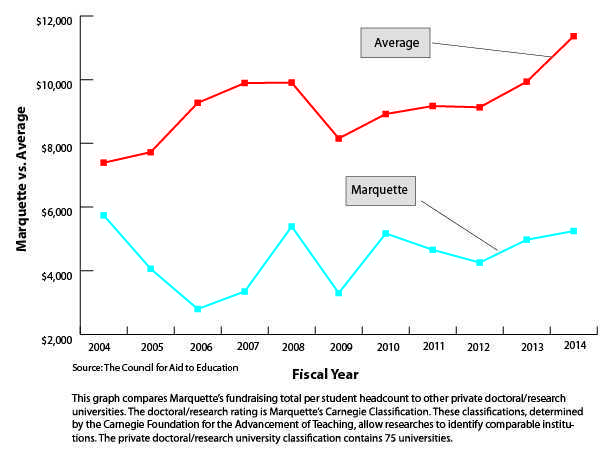

AN OVERVIEW OF MARQUETTE’S FUNDRAISING

In Fiscal Year 2013, contributions to Marquette made up about a tenth of the school’s total revenues, which stands in contrast to the university’s revenue streams a decade ago. Between 2001 and 2004, contributions consistently made up closer to a fifth of the school’s revenue streams.

It is important to note, however, the university was in the midst of its eight-year Magis campaign during these earlier years. The campaign raised a total of $357 million in new commitment for the school, beginning with a $10 million gift to help build the Raynor Library and concluding with a $28 million donation from J. William and Mary Diederich to transform the College of Communication.

The majority of the Magis Campaign was orchestrated under the leadership of Julie Tolan, who served as vice president for university advancement from 2002 until her resignation in 2012. Tolan, who is currently CEO of the YMCA of Milwaukee, declined to comment on this story.

Despite Tolan’s success during her time at Marquette, the school and the rest of higher education came to an unexpected hurdle when the recession hit in 2008.

“The economic environment really changed our world,” VanDerhoef said. “The philanthropy sector felt the same pinch as every other part of the economy.”

During this period, University Advancement shifted its focus from organizing a new campaign to simply maintaining the school’s top projects.

Marquette’s cost to raise a dollar substantially increased, while the school’s return on advancement investment dropped to less than $3 gained every dollar spent in fiscal year 2012. By comparison, Marquette made more than $9 for every dollar spent at the height of its Magis campaign.

VanDerhoef effectively took over university advancement in September 2013, a month before the Rev. Scott Pilarz left his role as university president, bringing Interim University President the Rev. Robert A. Wild back to the helm of the university. VanDerhoef described this change in leadership as a “real blessing.”

“He’s got 15 years of fundraising under his belt,” VanDerhoef explained. “For me to have the opportunity to work with him as I was getting up to speed was something great I had not anticipated.”

A RISE IN FUNDRAISING EXPENDITURES

Despite economic interruptions in the philanthropy sector, universities across the nation continued to increase expenditures for fundraising. In a study of 16 four-year Jesuit institutions’ tax documents, money going to fundraising at almost all schools jumped up by millions of dollars.

VanDerhoef emphasized these expenditures are seen as investments for the university.

“Universities and colleges are seeing that this is one of the most important sources of revenues,” he said. “Enrollment drives everything, but second to that is advancement.”

According to the tax documents, this trend is really isolated to the past decade.

“It’s kind of a chicken and egg thing,” VanDerhoef explained. “We saw more potential, so we starting spending more money to chase more potential — and that’s been across all higher education.”

Still, fundraising expenditures do not always track one-to-one in terms of the funds a school receives in return. VanDerhoef said an increase in investment is not always going to show an improved ratio, mostly because there are too many variables at play, including the economic environment.

As a result, schools like Marquette spend millions more each year without a necessarily impressive yield. For example, in 2009 Marquette spent $15 million for advancement and collected $38 million in revenues. By comparison, in 2004 it spent half the amount and pulled in $65 million.

“I think what has happened is advancement has taken a bigger and bigger role in student financial aid,” VanDerhoef said. “If I look at this year and what we have been able to accomplish, we really focused on how to produce better results. So when we get done with the year, we will see better results than what we’ve seen over the last handful of years.”

University Advancement set a goal to raise $40 million and it surpassed that amount in March. Susan Teerink, director of the Office for Financial Aid, said $14.5 million was raised so far since July specifically for scholarship aid.

The university spent a total of $109 million last year for student financial aid, discounting about a third of all tuition fees charged to students, according to data from the Office of Finance.

“University leadership continues to be focused on making a Marquette education as affordable as possible,” Teerink said in an email. “Father Wild has consistently encouraged alumni to donate towards scholarship aid, which will continue to benefit students into the future.”

WHAT IS THE MONEY USED FOR?

Investment in advancement at Marquette has a variety of uses, covering all costs related to soliciting, receiving and processing all contributions from individuals, foundations or corporations. Salaries and human resources taking up a huge portion of resources for the Office of University Advancement. The department currently houses 125 staff members with 10 vacant positions, making it one of the largest non-faculty staffs in the university.

“We spend a lot of our resources on engagement activities,” VanDerhoef said. “We want to start our young alumni in that pattern of giving back to Marquette. We know that some of them will be our major donors for future deals, so we cannot neglect the relationships we form with students when they are here.”

He noted, though, the largest expenditure in the department went to direct fundraising activities. The Council for Aid to Education, which collects data on philanthropy in higher education, reported that in 2012 alone, Marquette spent $7.8 million on direct fundraising, which amounted to about 46 percent of Marquette’s total investment in advancement.

Part of the rise in costs for direct fundraising, VanDerhoef explained, went to cover the costs of new technology and innovative methods to capture contributions.

“Fundraising is more sophisticated now than it was 10 years ago,” he said. “We need to allocate resources into areas of opportunity that we did not have before. We need to invest in advance to make sure that we are raising money in new ways.”

HOPE FOR A BETTER FUNDRAISING ENVIRONMENT

Despite the recent lull in higher education philanthropy, there are signs that the sector is slowly regaining traction. The Council for Aid to Education’s most recent “Voluntary Support of Education” report, which surveyed 1,048 institutions, found that gifts to higher education in the last year finally surpassed pre-recession levels.

“2013 was a great year,” said Ann Kaplan, a data miner at the council and director of the survey. “Between 2009 and 2012 was a really tough time for everybody, but a lot of institutions did very well this time around.”

The survey found the colleges and universities took in about $33.8 billion combined in contributions during the last year with three institutions — Columbia University, Stanford University and the University of Southern California — raking in nine-figure gifts.

The concentration of contributions, however, does not delegitimize the industry’s progress.

“Even in the pre-recession era, giving was concentrated in a small number of schools,” Kaplan said. “We’ve got a pyramid where there’s a few at the top that make the most money. They always did and they probably always will.”

MU MOVING FORWARD

VanDerhoef expressed optimism for Marquette’s future fundraising efforts, even despite the school’s recent string of resignations in key administrative positions.

“(The change in leadership) hasn’t proven to be an obstacle to us in producing fundraising results, because we’ll have better results this year than in the last several,” he said. “As you would expect, it’s a part of the conversation that we have with alumni and donors in particular. What’s really been remarkable from my perspective is that people really are attached to the institution. They know that leaders come and go, and the attachment remains strong.”

And as the economy gets back on track, VanDerhoef said he expects philanthropy at Marquette also to pick up speed, just in time for a new university administration.

“We would have been in a campaign long before now had the economy stayed strong,” he said. “It is better this year than last year for sure, and I expect it will continue to improve.”

Still, Kaplan warned there is often a time lag before the results of any campaign can be seen.

“It really comes down to a relationship with donors,” she said. “Just like anything, it takes more than a year to develop.”