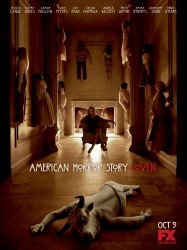

The third season of “American Horror Story” took a bow on Wednesday night, bringing to an end the anthology series’ most critically acclaimed installment. No matter what you thought of it, there is little debate that “Coven” was filled to the brim with storylines and themes that did not always work into the overarching story.

The third season of “American Horror Story” took a bow on Wednesday night, bringing to an end the anthology series’ most critically acclaimed installment. No matter what you thought of it, there is little debate that “Coven” was filled to the brim with storylines and themes that did not always work into the overarching story.

The witches of the coven died and resurrected over and over again, with seemingly no explanation, except Cordelia Foxx (Sarah Paulson) who lived to be Supreme, and poor clairvoyant witch Nan (Jamie Brewer), who never returned. The ultimate crowning of Cordelia as the next Supreme was expected, but the bizarre trajectory her character development took to get there was a jumbled mess.

Early episodes in the season included flashbacks to Salem, and an exhausted B-plot about witch hunters that ultimately went undeveloped. From episode to episode, it never truly felt like the hunters were much of a threat, and when Fiona decapitated the last of them, it was a merciful murder, the death of a storyline that truly had no where left to go. Stevie Nicks unnecessarily played herself, twice, and the storyline in which Patti LuPone’s bad mother character gave her son an enema fizzled out with no resolution. Star-power overpowered the necessity for a logical plot.

While “Coven” highlighted oppression of marginalized groups, racism and family – specifically the relationships between mothers and daughters – these big ideas, and a reasoned plot, played second fiddle to the individual, scurrilous moments that make Ryan Murphy famous. Clearly, the writers of “Coven” were driven by the desire for excess, ignoring the age-old sentiment “less is often more.” Buried underneath all the excess, however, is a burden that “Coven” bared all season: strands of misogyny and feminism, perception versus reality. These are crucial ideas that the classic-Ryan-Murphy moments of the season could not even overshadow.

So how does “Coven” deal with these two seemingly different dichotomies?

People often have a hard time differentiating between perception and reality, and Murphy preys on this inability in the show. Many times throughout the season, viewers unknowingly mistook what they understood for the way that it truly was.

In the first episode of the season, Kyle’s fraternity brothers violently rape Madison. She gets her revenge by flipping over their party bus, killing the majority of the perpetrators. Zoe’s emotional instability over Kyle’s death, however, persuades Madison to cast some black magic to resurrect him.

So yes, Madison has power over Kyle because she was the one who granted him new life. And we see this power played out over the season. Kyle is subservient to Madison, the two engaging in sex at her whim.

However, it is revealed at the conclusion of the season that Kyle still holds the power, as he strangles Madison to death for not resurrecting Zoe when she had the power to do so. We perceived Madison as having the power, but it was Kyle who seized it and quickly discarded her. Murphy clouds the lens through which viewers see the show, blurring the lines between how things really are and what the viewers perceive to be happening.

The line between powerful women and misogynist men is so blurred it requires careful attention to differentiate what is perception and what is reality.

Murphy’s used misogynistic tropes before. Just look at “Nip/Tuck.” However, “Coven” is explicitly about women who are literally empowered. Or so it appears.

Murphy’s true reality: the rollercoaster of witch alliances, and witch betrayals, at Miss Robichaux’s Academy for Exceptional Young Ladies suggest an underlying, misogynistic belief that strong females in close quarters can’t help but tear each other to bits, that one strong female in a room is more than enough.

Selfish tyrant Fiona slit the throat of her greatest threat to Supremehood, Madison Montgomery (Emma

Roberts); Madison resurrected and murdered Misty (Lily Rabe); Queenie (Gabourey Sidibe) befriended and betrayed Delphine (Kathy Bates); and Marie (Angela Bassett) and Fiona drowned Nan in a bathtub, not to mention the countless petty catfights in between.

“American Horror Story” has always loved its formidable women, but “Coven” took a different approach. It traded in women perceived to be strong-willed for a reality that dictates as men as the powerful ones.

We see this play out in the final episode of the season, which not only does a good job of wrapping up storylines, but also acts as a microcosm of themes present throughout the entire season.

At the onset of the young witches conducting the Seven Wonders, Cordelia regenders a Bible passage, stating, “When I was a child, I spoke like a child, thought like a child, reasoned like a child. But when I became a woman, I put aside childish things.”

This regendering is appropriate, considering that by the time “Coven” reached its conclusion, all the male characters have been killed, leaving only Kyle (Evan Peters) to be relegated to the status of butler, their watchdog.

Perception is Cordelia’s quote. Perception is Madison forcibly bewitching Kyle to kiss her and then immediately lick her feet, as if the power women have over men is romantic and subservient in one fell swoop.

However, this is the mistake of understanding things for the way they truly are. The men held the power when they were alive, and they still haunt the witches from beyond the grave.

When descending into hell as part of the Seven Wonders, Zoe wakes up startled, explaining Kyle breaking up with her repeatedly is her personal hell. If Zoe were a strong, powerful woman, her greatest fear should not have been dependent on how a man feels about her. This is Murphy’s true reality, that women are consumed with thoughts of being with men, for fear they will crush their little hearts.

In Fiona’s personal hell, she is trapped with The Axeman of New Orleans in a forested cabin. After he pours her a drink, Fiona spits it out, claiming it is not strong enough. The Axeman then demands that she come to him if she wants something stiffer, his hand placed firmly on his crotch.

It is crude jokes like these that advance the misogynist agenda of this season. Fiona is the most powerful Supreme of all, yet even the most powerful woman still suffers from the lewd and degrading comments of the men in the show.

Murphy’s past aesthetic was based on domineering men, and it appears to have found its way into “Coven.” Like the rest of the anthology season, I hope the next season leaves not only the plot and characters of this season behind, but also the themes. I look forward to Murphy exploring new motifs and ideas about what makes humanity tick.

And for goodness sake, I am ready to be scared again like I was when watching “Murder House” and “Asylum.” It’s time for the title to live up to its name once again.