Cary Gibson is a nice man. He sponsors a little girl from Indonesia, his wide set smile is infectious and he works for a charity program that feeds the hungry in Milwaukee, where he tries to connect with and inspire those who are down on their luck.

It’s hard to believe that only a few years ago, Gibson sat among them. For more than 20 years, Gibson, 57, lived as a homeless man on the streets, having to hide his few possessions in nooks around the city to prevent others from stealing them and living for a year under the Bronze Fonz statue on the Milwaukee river walk. He went six months without a shower, taking “mini baths,” where he’d only have the time to wash one part of his body at every bathroom he’d find before having to leave. He would binge drink, staying drunk for five or six days straight to numb the cold and numb the reality of his situation.

“You just get numb cold,” Gibson says. “Do you see the people in the summertime with big heavy coats on? I understood why they did that because those are kind of like blankets and were warm. Out in the cold, you’ve got a chill inside you that just don’t go away. Even when it’s 60 degrees outside, you keep that night chill with you all day. You could get up and it could be 70 degrees, but you’ve still got that night chill and you can’t get rid of that.”

Instead of worrying about Christmas shopping lists, Gibson worried about freezing to death in the cold, something that wasn’t uncommon for the homeless in years when the temperature hit below zero.

There was a silver lining, though, and it took the form of The Gathering, an organization working to feed the community that has served 121,958 meals to Milwaukee dwellers in need. Gibson works at The Gathering now, and Marquette’s hunger service group, Midnight Run, partners with them to contribute student volunteers to the project.

On days when Gibson would wake up in an abandoned garage with his beers in his sleeping bag (because it was so cold, they’d freeze to the point of being undrinkable if left alone), he would make the journey over to St. James Episcopal Church on 833 W. Wisconsin Ave., where The Gathering has one of its locations, in order to have a freshly cooked meal.

After spending almost 10 years as a recipient of The Gathering’s generous meal program, Gibson quit drinking and decided to pull himself up out of his situation, and he used The Gathering for support. Now, three years later, he works as the breakfast cook, making meals for people who are living out the ghosts of his past.

Gibson has been an employee at The Gathering for the past three years. He has a nice apartment and a steady income, a far cry from his days sleeping under The Fonz downtown, and he attributes this positive change of lifestyle to the work of The Gathering as well as Community Advocates, an organization that provides services to low-income and at-risk individuals and families.

America can be seen as the land of the plenty, but more than 50 million people like Cary Gibson still go hungry every day. Programs like The Gathering and Midnight Run are working to decrease this number, but they can’t do it alone. With a university dining program conscious of these problems and a multitude of convenient on-campus hunger-related service organizations, Marquette students have a golden opportunity to step up to this hunger challenge and be the difference.

Marquette dining services are well aware of the hunger problems plaguing Milwaukee. As members of the Marquette community, the homeless may seem worlds away, but a glance at the mix of people along Wisconsin Avenue on any given day proves that Marquette isn’t as far removed as some think. Keeping this in mind, the Marquette dining program has worked to contribute leftover dining food to the fight against hunger.

Most of the salvageable leftover dining food is donated to the Marquette branch of a program called Campus Kitchens, an on-campus organization that provides student-powered hunger relief to the Milwaukee area by taking advantage of Marquette dining hall leftovers, among other things, in order to assist the community while avoiding wastefulness.

The Marquette branch of Campus Kitchens operates right under students’ noses out of the O’Donnell Hall basement, which used to house an additional on-campus dining location. The bones of O’Donnell’s culinary past have been revived and now serve as a home for Campus Kitchen Marquette, which makes good use of the large freezers and pantries that can hold the sizable amount of food that Campus Kitchens requires.

“They have their own offices, their own kitchen, their own equipment, all that good stuff so that they can really take it to the next level,” says Kevin Gilligan, general manager of Marquette University’s Dining Services. ”Last I looked, they were at about 500 meals a week.”

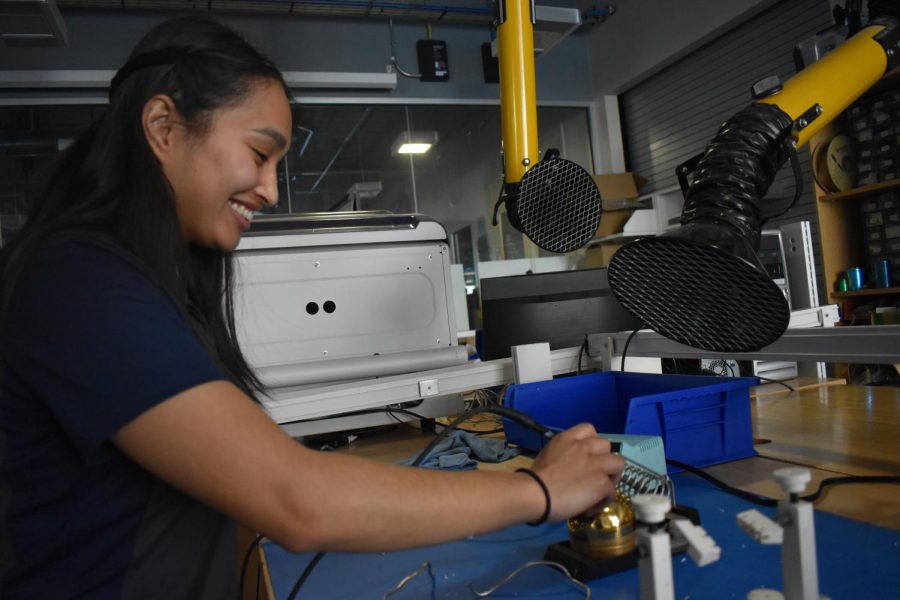

Most Campus Kitchen volunteers are students, with 8 to 10 volunteers every week night. Part of what makes volunteering for Marquette students so easy is that it is conveniently located and doesn’t require a weekly commitment, which is a problem that full-time students sometimes run into with other hunger relief volunteer programs. Angelica Shanahan, junior in the College of Nursing, praises the program for its flexibility, explaining that if a student has some spare time or is invited by a friend to join in at the last minute, like Shanahan was, there isn’t a standing commitment to Campus Kitchens beyond each individual day.

“We show up, sign in and put our little hairnets and aprons on, and then there’s a recipe that the leader has of a dish she wants us to make. It’s usually something like a casserole or something we can kind of throw together,” Shanahan says.

Unlike a standard food pantry, Campus Kitchen does not focus on giving out canned and frozen foods to the hungry, but rather collecting these things and turning them into pre-prepared meals, filling stomachs with hot homemade food. Many of the people that Campus Kitchens serve may not have access to hot meals regularly, so staying particularly health-conscious is important in order to fit the needs of the people they help.

“We keep it really healthy because we never know the people who we’re serving and if it’s their only meal for the day or not,” Shanahan says. “A lot of them are little kids, too, so we want to make sure that we get them something healthy.”

While the dining halls are the main source of food for Campus Kitchen, they aren’t the only donors. After they finish serving up peppermint mochas and caramel macchiatos during the day, the Starbucks on 1610 W. Wisconsin Ave. also sends over their leftover pastries to O’Donnell for Campus Kitchen, adding to the supply of spare baked goods that are wrapped up in neat little bundles and used for desserts.

Despite the care and attention that Campus Kitchen pays to maintain an environmentally friendly foundation with their use of leftovers and garden project, according to Gilligan, not all leftovers from the dining halls can be donated to Campus Kitchens. If a food item “crosses the counter,” or is served to a student, it is considered compromised and must be thrown out, without exception. The sushi rolls sold at The Brew and the AMU must also be tossed, and while these exceptions are unfortunate, they are necessary for sanitary reasons.

Brandon Placher, a former Cobeen dining hall worker and sophomore in the College of Arts & Sciences, described this issue as somewhat of an inevitability during his time at Cobeen.

Placher recalls his days of serving up crispy French fries at Cobeen with fondness, though it is precisely this food item that seemed to end up in the garbage cans behind the dining hall at the end of the night.

While Campus Kitchens comes around to pick up food from the dining halls and the Brew, according to Placher, they generally do not take cooked food, even when the food is in good condition. The result is typically a wasteful exhibition out in the alleyway with a garbage can of untouched food.

“Cooked food really can’t be kept, so obviously that just has to go, otherwise it’ll go bad,” Placher says. “Preserving it wouldn’t be healthy.”

Without a recipient to donate the food to, unused food needs to be tossed, not stored, in order to maintain sanitary conditions.

Scott Marshall is the Director of Development at Hunger Task Force Milwaukee, an organization that grows, collects and distributes food donations to food programs in Milwaukee like The Gathering.

Marshall explains that prepared food has a shorter shelf life and requires a plan or donor/recipient relationship in place to set up what he calls a “food rescue.”

“Say we knew over the weekend that Marquette would usually have leftover ‘bladidy blah’ of food. We’d have to determine if it’s efficient for us to go out and get that food, and we’d probably have to set up for it to be used as a meal, probably that next day, because we can’t hold on to that,” Marshall says. “But we need to know when we’re picking it up, we know when we’ll have it in house, we have a ballpark idea of how much it’s going to be every time, and so we set up to receive it immediately. We don’t sit on prepared food, we have to have a plan.”

It is here that the problem of connecting the dining halls to food banks and shelters reveals itself; the amount of Marquette leftovers each night is inconsistent.

Marquette actively attempts to minimize leftovers to be cost-efficient and less wasteful, which means that getting a “ballpark idea” of how much food will be left on each particular day is almost an impossible feat.

In addition to this, Placher insists that typically, not much even has to be thrown out in the first place. Anything uncooked at Cobeen gets put back into freezers and is marked so that it can be used before it expires, and nothing at any of the deli stands on campus is thrown out since sandwiches are made in front of students in the dining halls. Like the deli foods, grilled foods are made-to-order, meaning there aren’t leftovers at all because there is never a surplus.

The exceptions to this include Placher’s very own French fries, as well as the meals of the day, such as the creamy mac-and-cheese and chicken nuggets at Cobeen. With these foods, the difference between wastefulness and resourcefulness is a matter of correctly estimating when to stop cooking more food, creating a system vulnerable to small mistakes. Even though the operation is susceptible to these wasteful errors, Placher insists that the full-time workers are familiar enough with the ebb and flow of the dining halls to predict how much food is needed.

“I wouldn’t say too much gets thrown out, unless someone makes a mistake in their line. That was kind of a nightly thing, so it would vary, but it’s not like things were getting wasted left and right,” Placher says. “Not much” typically translates to about one small trash can a night, nowhere near enough food for a donation to a hunger-relief program.

Cobeen and the other dining halls work with hot, prepared food, which the leftover process reflects. The Brew, on the other hand, works a bit differently. Since the food sold there is mostly pre-packaged by Sodexo, with the exception of the sushi, it can all be donated to Campus Kitchens after closing, with the pastries going towards dessert packages and the prepackaged goods sent to be deconstructed for raw materials that go into the meals that Campus Kitchens creates. Even the fruits are composted at the garden project outside of O’Donnell.

The pastries sold at The Brew are made in the bakery in Humphrey Hall, which Gilligan says makes as much use as possible out of the dining hall leftovers, from the French fries to the bananas.

“When bananas are just past their prime, they’re great for baking, so we collect these bananas that are just past their prime and we send them to our on-campus bakery, and they’ll do banana bread or banana bread muffins,” Gilligan says.

While increasing the number of banana bread loaves using recyclable means is certainly positive, there are problems with Brew leftovers that slip through the cracks. The Brew has a special system for their excess food that is laid out by Sodexo, but it is a system that isn’t implemented on a daily basis.

Kaitlyn Rose, barista at The Brew Bayou and junior in the College of Arts & Sciences, wakes up at the crack of dawn every Monday at 6:15 a.m. to open The Brew and make six pots of coffee. She kicks off her week to the smell of fresh brewing coffee as she brings pastries made in Humphrey from a special cooler to their designated spots at The Brew, making sure to open the register while she’s at it. Each morning, she typically brings about one hundred bagels out for hungry students to grab and munch on before 8 a.m. classes begin. Each item is meticulously counted and placed, but by the end of the day, whatever is left is up for grabs.

“Some days it’s like cleared out,” Rose says. “I worked a Sunday night and there were two bagels left, which is great, because then we don’t have to throw those out.”

Campus Kitchen does come around to collect the leftovers, as they do with the dining halls, however, Rose says that they don’t come every day, which can be problematic.

“It kind of sucks because it’s on them to show up. So if they don’t have a representative show up, then we’re like ‘oh, we have to leave,’ so we have to throw this stuff out,” Rose says. “But if they show, they take everything. I worked a couple weeks ago and I gave them a whole garbage bag full of bagels and Simply To-Go sandwiches as well.”

Mondays and Tuesdays attract big rushes of hungry students to The Brew, according to Rose, so many of the bakery items are sold without hassle, but Thursday nights are slower. This wouldn’t be a problem, but Rose says that Campus Kitchen only comes to the brew Sunday through Wednesday nights, leaving three nights when the trash bin is the only option for leftovers. To compensate for this, the Brew orders fewer bakery items on off days so that not as much is wasted, but the disconnect between the days with heavy student traffic flow and the days on which Campus Kitchen comes is a shortcoming.

Students care about these dining discrepancies, even if it doesn’t manifest as outright concern. For sophomore Bri Erhard, her concern over food and hunger means giving time on a weekly basis to The Guest House shelter on 1216 N. 13th St. as a site coordinator for Marquette’s Midnight Run, a Marquette volunteer group that focuses on the hungry and homeless people living in the community surrounding Marquette.

“I went on CLR (Christian Leadership Retreat), a retreat before freshman year, and I heard about Midnight Run. I always participated in community service in high school, so I thought it would be a great way to connect to the Milwaukee community because I’m not from the Midwest so I didn’t really know anything about Milwaukee,” Erhard says.

While there has certainly been progress with Marquette’s response to hunger-related programs, there have been unmistakable challenges along the way. Unlike Hunger Task Force’s challenge of finding enthusiastic volunteers, Midnight Run has the opposite problem.

“We always have at least 75 students on the waiting list because, unfortunately, there are only so many spots we can have because we can’t take 20 people to a site that only needs five people serving,” Erhard says.

In order to reward continued service, Midnight Run has two separate volunteer times at the beginning of each semester for interested students, but these times favor returning students over new volunteers by allowing veterans to sign up and acquire spots in the program the day before sign ups are open to other students.

“Sometimes it fills up within the first hour,” Erhard says.

A whooping 75 students every semester sit idly on waiting lists for Midnight Run, hoping to volunteer and contribute to the program, but not being given access to a weekly outlet.

Wasteful, but in an entirely different way.