As part of the yearly back to school routine, a Marquette student browses the books he’ll need for class. Photo by Emily Waller / emily.waller@marquette.edu.

When students look forward to returning to campus, they think about reuniting with their friends, not shelling out money. But one glance at the book list brings them back to the sobering reality of college costs.

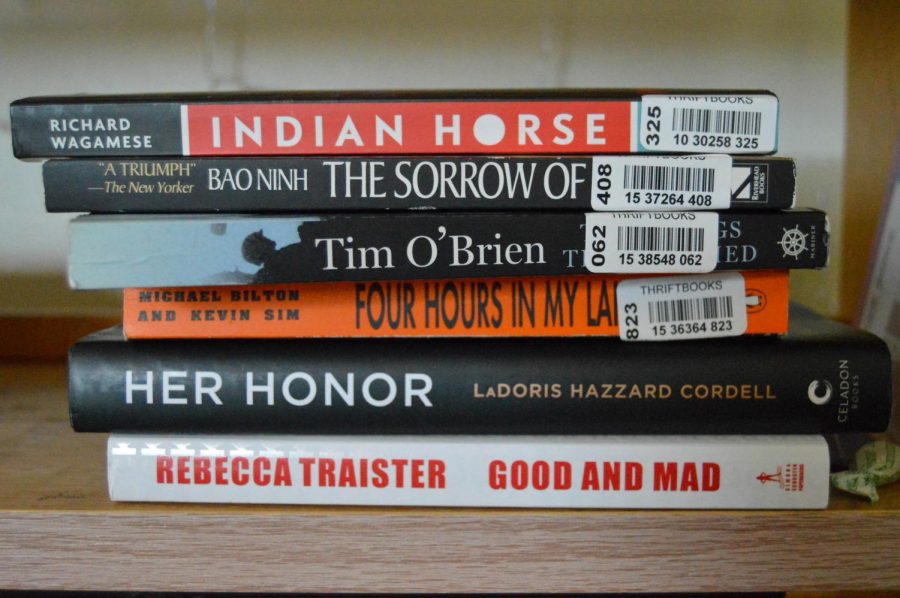

Students have complained about textbook prices for decades. A semester’s textbook costs are unpredictable, ranging from a few hundred to almost a thousand dollars, making budgeting difficult.

Federal legislation that went into effect July 1 attempts to make course materials more affordable while providing transparency of how textbooks are selected, purchased and sold.

Although the law is clear about how publishers, universities and others involved in the textbook application process will be affected, whether the law will provide students with significantly cheaper course materials or just slightly cheaper books is still to be determined.

The textbook market process

In a normal economic market, consumers choose products for themselves and determine how much they’re willing to pay for a certain product. If a product is more than what a consumer wants to pay, they can choose to do without the product.

Not in the textbook market.

Instead of students choosing what they’re willing to pay, a third party – the professor – determines what the student needs to succeed in the course and that this need outweighs the cost of the book.

Nicole Allen, textbook advocate for Student Public Interest Research Group, compared the textbook market to the prescription drug market. Doctors are the only ones who know which drug is needed to cure a patient, just like professors are the only ones who can choose the best learning materials, she said. The problem with this, she said, is neither the doctors nor the professors are buying the products they prescribe themselves, making them less sensitive to prices.

Textbook prices are rising at four times the rate of inflation for finished goods, she said.

Allen said although the legislation will lower costs in the short term while driving them down in the long run, high textbook prices cannot be solved with legislation entirely. What the new law can do is make this special market more like a normal market where the rules of supply and demand apply, she said.

The government did the best it could, she said. She believes the next step is providing professors with more cost-effective options.

Select, buy, sell

The legislation aims to affect change at every step in the textbook selection and buying process.

The first step: professors choose a textbook. They find books by looking at syllabi of professors at other universities, attending conferences, remaining up to date about recent scholarship in their field and considering books marketed by publishers.

Choosing textbooks varies by discipline, said Michael Monahan, a Marquette philosophy professor and director of the university’s core of common studies. Monahan said he looks for a book that includes all the topics he wants to emphasize, trying to make supplemental materials unnecessary. If he finds multiple books that fit his criteria, Monahan then chooses the cheaper book.

As soon as you start teaching, publishers start contacting you about their books, Monahan said.

The new law states when publishers market books to professors, they must provide in writing the wholesale price of the textbook, copyright dates of the last three editions, a description of changes between the editions and whether any other formats of the book are available.

According to Bruce Hildebrand, executive director for higher education at the Association of American Publishers, publishers have been providing this information all along so the new law isn’t a problem for them. Changes to textbooks are listed in the beginning of the books and prices can be found easily on the Internet, he said.

But according to Allen, only 23 percent of professors rate publishers’ Web sites as informative and user friendly.

“Just because information is available doesn’t mean they have it,” Allen said.

At Marquette, once professors choose books, they fill out a form with their department and BookMarq is notified of the decisions.

BookMarq then goes to the Office of the Registrar to find out how many students are enrolled in the class. Once BookMarq officials have determined how many books they will likely need, they purchase used books on campus or from wholesalers while buying new books from the publisher.

At BookMarq the prices of new textbooks are based off the publisher’s wholesale price and an agreed upon contractual margin. Used books are usually discounted 25 percent from the cost of a new book while rentals are discounted 50 percent, said Elio DiStaola, director of campus relations for Follett Higher Education Group, the company that manages BookMarq for Marquette University.

Implications for the future

The most positive effect the legislation will have on the process is it will encourage faculty to get their book adoptions in on time, said Charles Schmidt, director of public relations for the National Association of College Stores. If a professor is using the same book for another class and the bookstore knows this on time, they may be able to buy back more books at a higher price, he said.

DiStaola agreed with Schmidt’s predictions, saying buyback prices have always been driven by demand. Stores can pay half the purchase price of a book if they know there’s an established demand, he said.

That could mean more money in students’ pockets when selling books back at the end of the semester.

One of the main reasons for a low buyback rate at the end of the semester is the professors haven’t chosen their books on time, Schmidt said.

Bundling books – selling multiple books in one package or selling CDs with a book – has become a common practice in the textbook industry. Now publishers have to sell books unbundled as well.

Hildebrand said publishers “just deliver the order” and were always able to sell books unbundled. He said buying all the books bundled is frequently cheaper than buying each book individually.

Yet, Allen said all the aspects of a bundle are seldom used and can drive up costs 10 to 50 percent.

And with booklists being published on Snapshot during registration, Marquette students will know what their tabs will be as soon as they sign up for classes. In the fall they may only pay $200, while in the spring their books could soar to $800.

For students who don’t have that kind of money just lying around, Allen said the new legislation will help them set aside the cash they will need later.