Her name is Ashley. On Mondays she goes by “Ee-cee.”

Though wise with age, they can’t pronounce Ashley.

They are four Mexican immigrants, mostly in their 50s, who have been dropped in a strange country with strange traditions and a strange language. On Mondays, Ashley Kennedy teaches them English.

“Why study Spanish?” they ask Ashley, a senior in the College of Business Administration. Ashley is already fluent in English — why waste her time?

“They can’t believe it when I say I’m studying Spanish because they’re struggling to learn English,” Ashley said.

A struggle it is. Most of Ashley’s students work in factories. A growing number are unemployed. They used to work in Milwaukee’s tanneries, she said, but many were shut down when the recession hit. The rest of the tanneries were outsourced to Mexico.

They joke about it, her students.

“I just left Mexico to find work,” the students say. “Now my work has gone to Mexico.”

Regardless, the students need to find work in the States. To do it, they need one thing — English.

*

Ashley teaches an English as a Second Language class at Milwaukee’s Council for the Spanish Speaking Inc. She wanted to keep up her language skills even after completing the credits for her Spanish minor, so she volunteers her time once a week.

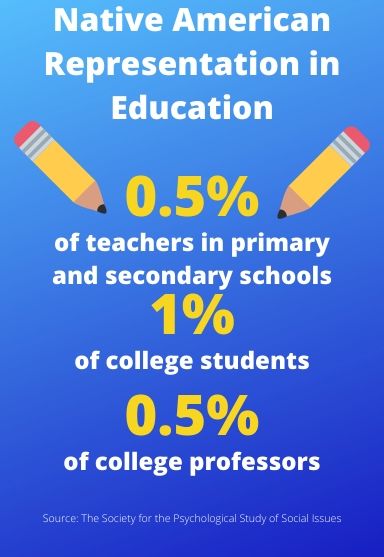

Of the 45 million Hispanics in the United States, just 61 percent are proficient in English, according to the Pew Hispanic Center. In 2007, Milwaukee County was home to more than 110,000 Hispanics, a number that’s been steadily growing since 2000.

The Council for the Spanish Speaking provides this growing community with programs in housing, education and human services. Located in the heart of Milwaukee’s South Side, the Council specializes in teaching English as a Second Language. It also offers classes toward a high school equivalency diploma and certificate of general educational development. With classes in citizenship, driver’s education, financial literacy and computer skills, the Council is also a site for many Marquette service learners.

Kim Jensen Bohat, director of Marquette’s Service Learning Program, said the university has maintained a relationship with the Council for the Spanish Speaking for at least 10 of the program’s 15-year existence.

“Our students get a lot of experience being able to speak Spanish and engage with a diverse population,” she said.

Since the program began in 1994, service learning has been incorporated into more than 240 courses ranging from nursing to writing to television production, according to the Service Learning Web site.

The Law School and the Dental School have their own outreach programs and don’t formally participate in Marquette’s service learning, Jensen Bohat said.

The program sends 1,000 to 1,200 students to more than 100 different service locations each semester, she said.

Jensen Bohat estimated that about 10 percent of students continue volunteering with their service learning organization after they have fulfilled class requirements.

“They can get hooked and feel like a part of the agency, so they come back either on their own or with another service learning course,” she said.

Ashley worked with the Hispanic population through service learning at Notre Dame Middle School near the South Side before studying abroad in Madrid. Spurred by a professor’s suggestion, Ashley got involved with the Council for the Spanish Speaking upon her return to the States.

“I realized I didn’t want to come back and not have Spanish be a part of my life,” she said.

*

Some students come to the Council without any previous education, not even from their home country.

Elizabeth Pizano, a basic English skills instructor at the Council for the Spanish Speaking, oversees Ashley’s classes and knows how exhausting lessons can be week to week.

Some students only come for the first few classes and don’t show up for the rest. Obstacles in students’ personal lives – such as health, travel or time – cause them to miss class, said receptionist María Lerma. Because of the high turnover, she estimated there are only 50 students currently attending classes at the Council for the Spanish Speaking.

Classes are free, save for a $10 registration fee. It’s very affordable for members of the minority group that has some of the lowest salaries in Milwaukee. But the financial investment isn’t what motivates students to attend.

It’s personal drive that gets students to show up.

“They’re here because they want to be here,” Pizano said.

Many of the students are dislocated workers, meaning the plant they worked at has closed or they’ve been laid off. Dislocated workers can get government-sponsored post-dislocation training – and collect an unemployment check – if they attend 20 hours of English class each week at the Council for the Spanish Speaking, according to Pizano.

Pizano said these classes offer students a more open, casual opportunity to learn through conversations in English. Because the South Side of Milwaukee is densely populated with Spanish speakers, English practice is valuable.

“On the South Side they can survive,” Pizano said. “But to move on they need to know English.”

For Ashley, sharing her English skills with Milwaukee’s Hispanic community has proved to be more than just Spanish practice.

*

Ashley had a conversation about dreams one day in her class.

“If you could go anywhere in the world, where would you go?” Ashley asked.

“Well I don’t have any money,” one student said. “I don’t want to think about it.”

Ashley tried again.

“What would you tell someone who wants to travel to your native country?”

A woman named María answered, “Don’t go. You’ll get kidnapped and killed.”

María knows. Her son-in-law was “chopped up” simply because he was from the Mexican city of Jalisco. Now María is here, feeling helpless.

“She’s tired from life,” Ashley said.

María isn’t at the Council for the Spanish Speaking to really learn English. She’s there to collect her unemployment check, Ashley said.

“I’m just too tired,” María told Ashley at a teaching session. “I don’t want to work any more.”

After 30 years of factory work in Milwaukee, all María wants to do is cook for her grandkids, Ashley said.

“It’s disheartening,” she said, to know that after more than 30 years in America, María just wants to cook. And English is just an unemployment check.

“It’s weird to me to think you can live in a country for 30-some years and have so little English,” Ashley said.

Although María has very small hopes of learning English, many of Ashley’s students do make great efforts to learn the language. They want to – but it’s not easy.

Most students can speak bits and pieces of English, Ashley said, but they can’t write it.

When Ashley asks them to write down where they want to travel, they groan. It takes a long time, and they usually don’t get it right.

“When people aren’t literate in their native language, how can they learn grammar in a foreign language?” Ashley asked.

The students often ask her to explain the grammar rules they struggle with so much. Ashley often has to say she doesn’t know.

Grammar frustrates Ashley, especially when she can’t give her students a solid explanation of why the rules are the way they are. That’s just how we do it here.

But amidst participles and antecedents, she does find fulfillment.

“There are days I dread it,” Ashley said. “Then I get there and every time when I’m done, without fail, I feel better. It’s a selfish feeling, but you feel better. When they ask, ‘You’ll be here next week, right?’ That’s all I need.”