In 1993, Victor Ambros made a pioneering discovery in biology, uncovering microRNA, a genetic material that guides protein production.

Over 30 years later, international recognition made its way into the hands of Ambros and Gary Ruvkun, who were together awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work with microRNA.

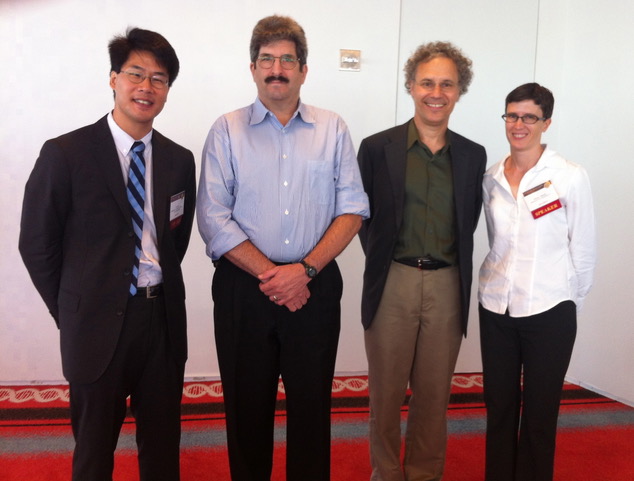

Allison Abbott, an associate professor of biology, was a postdoctoral fellow studying in Ambros’ lab from 2001-2006. His curiosity-driven approach to microRNA investigation has made its way to Marquette in the form of Abbott’s lab, which continues the research started by Ambros.

C. elegans is a microscopic nematode worm that measures approximately a millimeter long. It serves as a model organism, meaning that it is used in biology to study phenomena such as microRNA. The transparent worm model is used in Abbott’s lab at Marquette and in labs around the world.

“I think the worm system is great to work with,” Abbott said. “I have a lot of undergraduates in the lab. I have graduate students in the lab. And in some ways, it’s very easy to do experiments. We can train students to work with the model system, and there’s lots available to us as far as what we study and how we do it.”

As a model, the worm is then used as an organism in which to study microRNA. Its composition of less than 1,000 cells, transparency and microscope-friendly size make it a preferred species in biological studies, especially in microRNA research.

“So, we have to try to figure out what [the microRNAs are] binding to in the worm,” Abbott said. “The direct targets would be what mRNAs do they directly stick to and then what do those targets then do to affect the growth and development of the worm.”

The lasting influence of a Nobel Prize in the lab has created an environment that is both curiosity-driven and inspired to do impactful work, according to Abbott.

“I always tell people, whenever I tell them about the research, ‘A Nobel Prize is close to me,’” Rita Okeke, a graduate student in Abbott’s lab, said. “It makes me feel as if what I’m doing in the lab is really, really important. Whoever wins the Nobel Prize on anything, that thing can or has the capacity [to] impact humans in the long-term.”

Lisa Petrella, an associate professor of biology, was responsible for breaking the news to Abbott that Ambros had won the Nobel Prize.

“I was at a conference on Long Island. I couldn’t sleep, so I woke up early and I [was just] on my phone. I’m like ‘Victor won, Victor won!’ and I texted her,” Petrella said. “It was 6 a.m. on the East Coast, so I expected she wouldn’t be up. She was up but hadn’t looked at the news, so we were texting back and forth and it was really fun.”

The moment was joyous for Abbott, who was delighted to hear that the honor had finally found Ambros.

“Hearing and realizing that was so amazing,” Abbott said. “He’s a wonderful scientist, so it’s exciting.”

Abbott had grown to wonder if the recognition would come for the work done by Ambros and Ruvkun, as other honors had been previously awarded to biologists working with RNA.

“I think sometimes findings don’t announce their significance until later on, with the perspective of, ‘Okay, now we know that they weren’t a very strange worm regulatory phenomenon.’ They were representative of how genes are regulated, sort of in all organisms,” Abbott said.

The continuation of Ambros’ work in Abbott’s lab has allowed Marquette to expand upon award-winning biological ideas.

“Even though we are not working to win the Nobel Prize, it’s going to add so much to the field if we finally put some of the pieces together,” Okeke said. “And it’s something of great joy. If someone says, ‘Oh, we know that this microRNA does this, and the research was done in [Abbott’s] lab at Marquette University,’ [that’s] really, really an amazing thing.”

This story was written by Lance Schulteis. He can be reached at lance.schulteis@marquette.edu.