Black girls, that soon become Black women, learn at a young age that they are valuable. Not the kind of value that makes diamonds attractive, but the kind of value that makes us vulnerable to human trafficking. Because everyone knows, when Black women and girls go missing, the world goes silent.

Not the kind of silence that is mournful or reflective, but the kind of silence that continues the cycle; that is passive in its origin. While families mourn the absence of daughters, nieces, mothers and wives, we have learned to move on and move forward – overlooking the community of women we’ve left behind. It is as if their bodies are laid out on the concrete pavement and we have learned to dance between them.

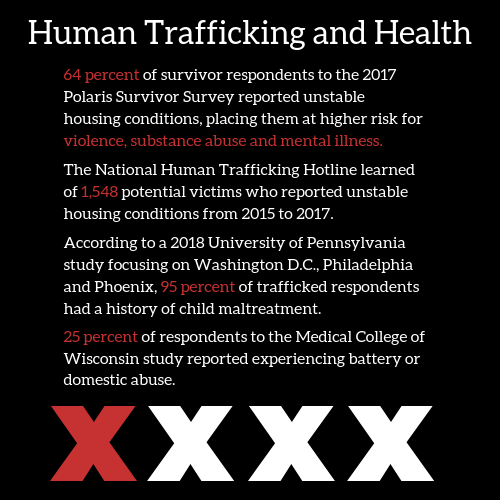

Human trafficking, as defined by federal law, is sex or labor trafficking that is obtained by force, fraud or coercion. In 2020, the Human Trafficking Institute ranked Wisconsin as the sixth in the nation for human trafficking cases, Milwaukee, in particular, being a hot spot for this issue. Through a geospatial analytic study released in 2020 conducted by the City of Milwaukee, it showed that victims are often trafficked in six zip codes including 53206, which is located in Southeast Wisconsin has more than 95% of Black residents.

For me, this begged the question: what is Marquette doing to address the ongoing threat human trafficking poses to women of color on campus? Despite trafficking numbers rising in the city in 2021, this does not seem to be an area of concern to the institution.

Marquette is not an automatic safe haven for Black women and girls.

Although I am from the North side of Milwaukee and have been conscious of human trafficking at a young age, I had a false sense of security when navigating campus due to its location. It is far better than the neighborhood I grew up in, so I no longer viewed myself as a target for human trafficking. But earlier this year, I was brought back to reality.

As I was walking toward Wisconsin Avenue and 17th street, I was approached by a man who said his friend saw me while he was driving, was new to the city and thought I’d be the perfect friend to have. As he walked and talked with me, he further explained that his friend thought I was beautiful and could use me for something but wouldn’t tell me what that something was. In order to find out, he asked me to wait for his friend to come back around the block so that we could talk more in a private location.

He told me to stay put while he bought an item from Walgreens, but I knew if I waited, even a second, I could have been the next Black woman plucked from society never to be found again. So, I ran. I didn’t know where I would go or what to do next, but my feet had a compass of their own, almost as if knowing how to fight for my life was embedded in my DNA.

I eventually made it to a safe location where I called the Marquette police. Within 10 minutes they arrived and I explained to them what happened and why I felt I was almost trafficked. They said that week, they had gotten multiple calls from women across campus, that shared similar stories. Coincidentally, I met two Black girls later that week that had shared experiences on campus that happened a few days prior to my own.

While Marquette has numerous safety resources available to students, faculty and staff such as monthly self-defense classes at the AMU, the university can do more to protect Black women and girls from trafficking, and it starts with raising awareness about the issue.

One idea to raise awareness, would be to hold a public discussion open to all community members about human trafficking and its effects on women of color across the city. Administrators would be invited to come and also could invite classes that deal with nonviolent campaigns like Theologies of Nonviolence or Intro to Peace Studies to join as well. Because to me, it is not about starting a movement, as much as it is about starting a conversation.

This could be the first step to protecting Black women and girls across campus because when the world goes silent, it is up to us to take a different path.

This story was written by Hope Moses. She can be reached at hope.moses@marquette.edu.