The Kasten Gym, Marquette’s practice basketball court in the Al McGuire Center, was filled with more than just players and coaches Oct. 6.

Associate professor in exercise science Kristof Kipp and his team of five graduate students position equipment around the court.

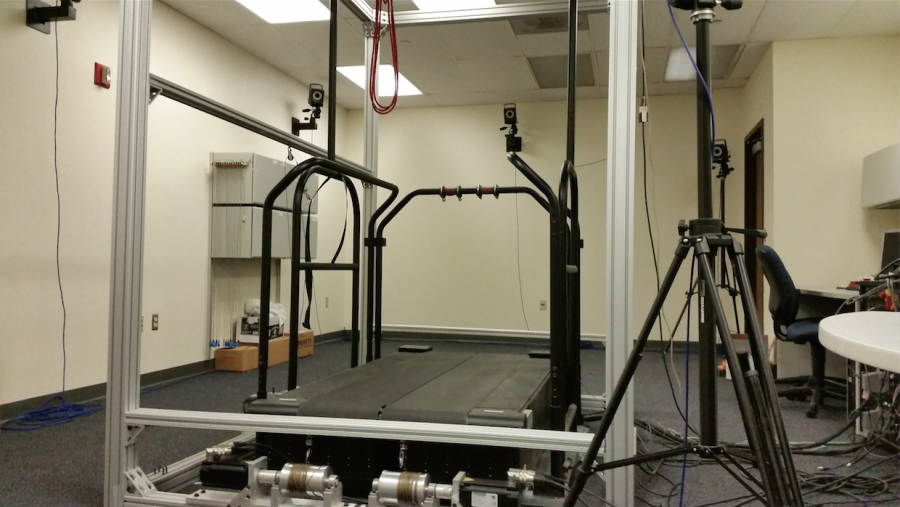

They arrange eight tiny Sony digital cameras on tripods surrounding the court. Players show up and begin shooting. Kipp and his team just press a button to record.

It’s similar to using an iPhone.

Back at their office or, as Kipp jokes, the “nerdery,” they run it through the computing system. When it’s processing, Kipp said it sounds like an airplane taking off. The computer takes around 30 minutes to create an avatar of the player.

This avatar pinpoints exactly how a player shoots to help them improve.

“The feedback you’re able to provide often is directly correlated with how complex the movement is that you’re analyzing or how complex the data is that you’re collecting,” Kipp said.

To capture human movement, exercise scientists previously used marker-based systems that would suction to the person’s body. Now AI creates the marker based on video footage.

“When you think of basketball, lots of things going on. Studying individual movements becomes difficult,” Kipp said. “But on a free throw, it’s a very controlled situation. No defenders. It’s just the person and the hoop.”

The shooting lab was a test to see “Is this really going to work?” Todd Smith, the assistant athletics director of applied sports science, said.

Kipp admitted that he wasn’t sure if he would even call this test research.

“It’s been mostly just testing the system out. How big of a space can we calibrate?” Kipp said. “Can we do free throws and three-pointers in the same session?”

Back in the spring, Todd Smith received a text from Kipp with an attached video about biomechanics in basketball that said, “Hey this might actually be a really good way of how we can help make a difference. What do you think?”

“I thought it was a great idea of how biomechanics can be of use to improve basketball shooting performance,” Kipp said.

Marquette is the only school in the Big East using equipment this way, but Todd Smith doesn’t think the equipment really matters.

“From what I’ve heard from a lot of places, it’s not so much the equipment, it’s about the people. If you have the right people, then you can get things done,” Todd Smith said. “Between Dr. Kipp, my staff and the basketball stars, that is the most important part because it’s the right people who will figure out how to do what we need to do.”

Todd Smith mentioned it’s also important to have the coaches care.

It may be easier for the coaches to buy in since men’s basketball head coach Shaka Smart and special assistant to the head coach Nevada Smith used similar technology when both worked at the University of Texas.

“You can give them a very pinpoint accurate data point. This is where you are, this is where you want to be and how to invest to do this,” Nevada said. “I think for guys who are very secure in what they’re doing, it just reaffirms what they’re doing is correct … I think guys who are changing their shot and the younger guys coming in, that’s going to be the biggest.”

This was something junior forward Olivier-Maxence Prosper echoed.

“It was interesting to see the technology, how it was able to analyze the shot and how consistent it was with everything,” Prosper said. “We will be able to see exactly what we need to adjust. I think it’s going to help us in the end.”

There are more benefits too.

Similar to concussion protocol pre-assessments, video of a player’s performance portrays a baseline for how they moved before an injury. It gives clinicians and rehabilitation professionals a goal to meet.

“Let’s say somebody has a sprained ankle, they’re coming back and their shots are a little different because they have a sprained ankle, then that’s beneficial for us to know that what we need to fix,” Todd Smith said.

While the basketball teams have used similar technology in the past, this markerless system is more efficient.

“That’s always the biggest thing I have to think about is the time commitment of the athletes,” Todd Smith said.

He recalled the markers would fall off if players were playing hard. It happened so often that the coaches created a game out of it: whoever lost their markers first wins.

“In ten years, marker-based motion capture may be kind of old news,” Mike Haischer, the research lab manager at the Athletic Human Performance Research Center and Ph. D. candidate in exercise and rehabilitation science, said. “The ability to collect data in a less intrusive, timely manner with the marker system is a huge benefit.”

Todd Smith thinks Marquette needs to think big and Haischer agrees.

“The possibilities are really endless,” Haischer said. “The fact that we’re not pigeonholed into being within a lab space on campus, doing marker-based data collection really opens the door to anything — any movements that the sport or coaches or performance coaches deem important.”

When looking at the big picture, the goals are similar. Todd Smith wants Marquette to be the “basketball university.”

“Everybody has an opportunity to get better. If we can clean up one little thing and the way each athlete moves, then I think that that would help that athlete,” Todd Smith said. “If you can help each athlete, one athlete at a time, then you’re helping the whole team.”

Haischer reiterates this belief.

“Make more buckets is the end goal,” Haischer said. “Make more buckets, win more games.”

This story was written by Randi Haseman. She can be reached at [email protected].