Pharmaceutical companies have the responsibility to uphold just and effective treatments for patients who are suffering, but even healing comes at a price.

A thorough understanding of the health care system and insurance industry is a dizzying, complicated mess, but there is one thing for certain: The United States does not strictly regulate the prices of medications. This means the decision of prices for medications is mostly at pharmaceutical companies’ discretion.

This was brought to light in 2015 due to Martin Shrikel, founder and chief executive of Turing Pharmaceuticals. Turing acquired a drug, Daraprim, which was a life-saving antiparasitic drug to help patients with both malaria and patients with HIV. Shrikel, a former hedge fund manager, took the drug’s original $13.50 price and marked it up to $750 a tablet for all consumers.

While it is not necessarily surprising that a former hedge fund manager made a decision to profit off of people’s healthcare, as hedge funds are typically considered a risky investment choice, there is something that was selfishly prioritized when making the decision to mark up the drug.

Large pharmaceutical companies put their own profits before the people they were serving.

This is not the only time greed has guided a pharmaceutical company’s financial decisions.

Companies like Turing Pharmaceuticals have developed a business strategy, where they acquire older medications like Daraprim and Cycloserine that treat rather rare but threatening diseases and mark them up to make a profit. Essentially, the rationale behind these markups is that the drug is so infrequently used that in order to make money off it, they have no other option but to raise the price.

While these medications are rare, it makes sense that they would need to fuel the revenue with added costs in order to stay cost-effective.

However, supplying these specific medications is not the only revenue source for these companies.

Opioids are a type of medication typically prescribed to patients for their pain-killing effect.

Currently, three million U.S. citizens have or had suffer from opioid use disorder. People with OUD suffer from withdrawal, need for increased doses and continuous life disruption.

Using opioids is far different from using an over-the-counter painkiller like Tylenol or Advil, as opioids treat moderate to severe pain and give the user a “high feeling” that can become highly addictive.

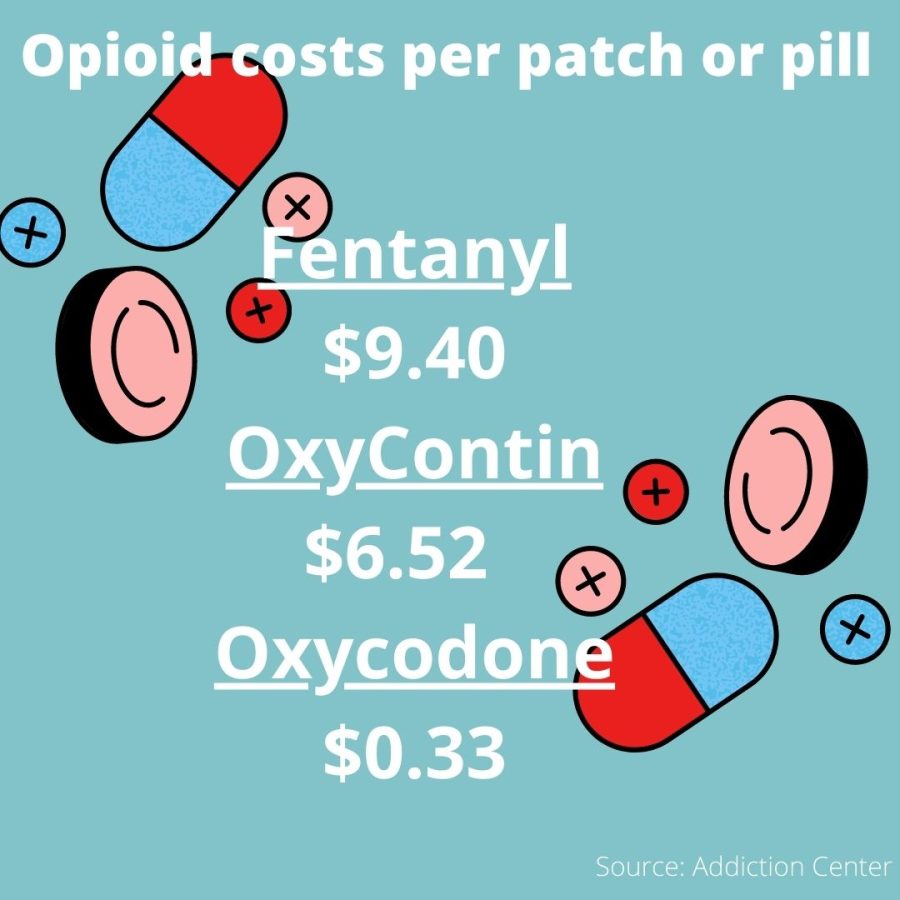

The average price of an opioid without insurance is remarkably low. Without insurance, a fentanyl patch is $9.40, OxyContin is $6.52 per pill and Oxycodone is as low as $0.33 per pill.

Health care should be easily accessible, but accessibility to highly addictive drugs that have resulted in an opioid epidemic should not be cheaper to obtain than other medications.

In the 1990s, large pharmaceutical companies pressured the medical community to prescribe opioids at a growing rate after suppressing knowledge that these substances were highly addictive as reported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. As opioids were being prescribed at higher rates, patient dependency on them grew and contributed to widespread misuse of opioids.

The Sackler Family who owns Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of the opiate Oxycotin, made over $10 billion in profit from the drug.

The Department of Justice reported in Nov. 2020 that Purdue Pharma pleaded guilty to fraud and kickback conspiracies after the company had marked and sold dangerous opioid products, even after the company had reason to believe that these products were “being diverted to abusers.”

Pharmaceutical companies argue that by charging more for drugs, they will not have the funds necessary to increase innovation and discovery in drug production. Without this innovation, they say, there will be no way to find new treatments for illnesses.

However, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that if the revenue generated by pharmaceutical companies was reduced, it would only result in two fewer drugs in the next decade.

Pharmaceutical companies also do not contribute to new drug development as much as they say they do. These innovations are usually due to research efforts that are funded by the National Institute of Health and independent philanthropists, not pharmaceutical companies.

There is no reason for a life-saving medication to be $750 while an addictive opioid can be as low as $0.33 without insurance.

This variability may be drastic, but it signals a larger problem within the unregulated economic sphere of health care.

This is not economic freedom; this is greed.

Greed runs these large pharmaceutical companies, as they put evil ambitions before the health and well-being of patients.

Last week, the House passed a bill to cap insurance co-pays at $35 every month for Americans. This is a promising start, but affordability and fairness must be widely accessible for all patients with varying ailments.

It is immensely frustrating to see that these companies are not responsible enough to understand the impact that their greed has on patients, irresponsible enough to have the U.S. government step in. There must be reform in the ethics of these companies to remember who they are serving.

This story was written by Laura Niezgoda. She can be reached at laura.niezgoda@marquette.edu