Marquette University lies on the homelands and waterways of the Sauk, Ojibwe, Fox, Ho-Chunk, Potawatomi, Mascouten and Menominee nations.

However, for students who wish to engage in the history and culture of the nations that lived, and continue to live, on the land where the university resides, their options are limited.

Marquette has one class, ENGL 4825, solely dedicated to Native American literature that is taught every semester by assistant professor of English Samantha Majhor. There is also ENGL 3780, Water is Life: Indigenous Art and Activism in Changing Climates, ANTH 3350 Native Peoples of North America and HIST 4155 A History of Native America.

In addition, there are certain sections of classes such as ENGL 4810 and ENGL 4820 that may touch on Indigenous issues. However, there’s currently no program in Indigenous studies at Marquette.

“Learning about Native American people and history and learning about Native ways of knowing and philosophies I think really opens up to students different ways of thinking and that’s really what we’re here to do here in college,” Majhor said.

Even with a lack of a major, there has been progress in increasing Indigenous education and representation at Marquette. The Center for Race, Ethnic and Indigenous Studies was developed within the past academic year.

“There are projects taking off, and I think this is only the beginning of Marquette’s expansion in this direction,” Tara Daly, co-director of the REIS program said.

Daly said that in the long term there are faculty who wish to develop a minor in Native American and Indigenous studies and eventually a major.

“REIS is in dialogue with the Haggerty Museum as well to plan an exhibit highlighting Native American and global indigenous arts for the Fall of 2023. We also are organizing a student-led mural project this spring and hope to collaborate with local Native American artists and students,” Daly said.

Marquette adopted a land and water acknowledgment and professor of history Bryan Rindfleisch worked on a map with students about the Indigenous history of Milwaukee.

“We have many affiliated faculty doing work on Native and Indigenous cultures, both in and outside the classroom,” Daly said.

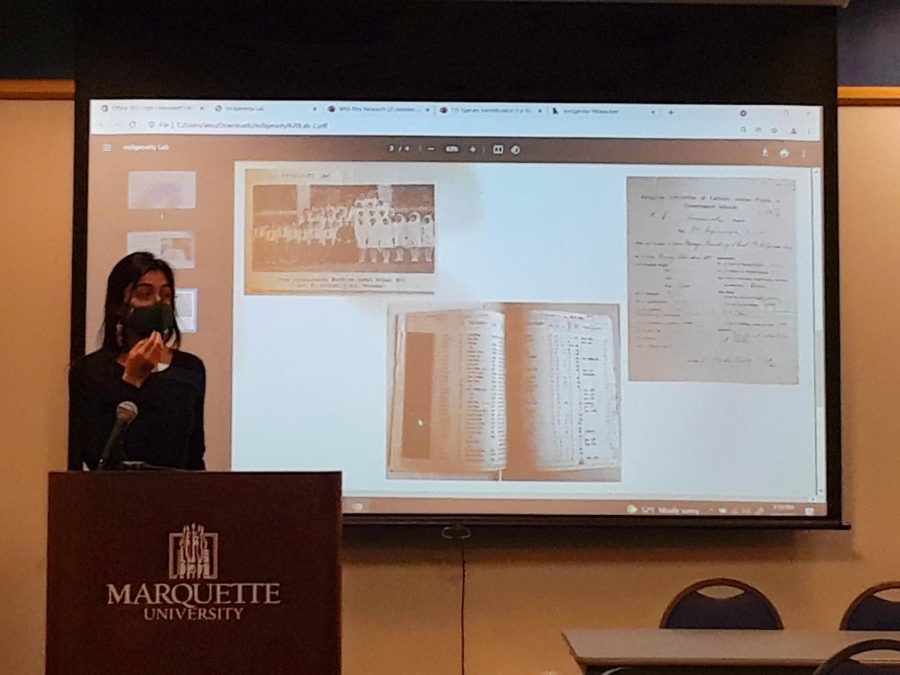

Last semester, Nov. 5 Marquette hosted the Critical Indigenous Symposium. The event featured faculty from Marquette and the University of Minnesota, as well as a group of undergraduate students from the Indigeniety Lab. The lab was a research group with a focus on understanding Indigenous roots and culture. Additionally, some students worked on ecological issues, such wild rice species identification to see if it could be reintroduced into the Menominee River Valley.

“The high attendance of this event attests to the growing interest in this topic and the dedication of Marquette to doing more work in this arena,” Daly said.

These developments are steps in increasing Indigenous education at Marquette, however, the university has not revealed any plans to change the university seal. The university previously said in July of 2020 that there were plans to change the seal and a seal redesign team was created in March of 2021.Though the seal has not been changed.

The seal inaccurately depicts Father Marquette leading Indigenous people, when in reality it was the other way around. This issue has been shown to the university by various members of the campus community.

Majhor said that increasing Indigenous education and representation is a “two-fold” issue.

“It’s about having a robust program where someone could build their knowledge about Native American history, arts, literature and issues. It’s also about having that faculty representation who are Native American and our Native students can see themselves reflected in them,” Majhor said.

Senior in the College of Education Rebecca Deboer is one of those Native students who saw herself reflected in Majhor’s class.

“Personally for me, I know that having an Indigenous curriculum and classes that talk about Indigenous topics and issues is incredibly important. I have never really been in places where any type of Native American or Indigenous experience was talked about until I got to school here. Even though there is such a lack of curriculum at MU,” Deboer said.

Deboer was one of the students who studied in the Indigeneity Lab and said that through her time at Marquette she has learned the “verbiage” to make sense of her experience as a minority on campus.

“Learning about Indigenous people and that for me was incredible because I never had felt like I was kind of validated in my experience because I wasn’t raised in Native American culture. I just was. It was something that I felt like I was,” Deboer said.

But studying Indigenous cultures and issues has benefits for non-native students and Native students alike.

“If you don’t understand Native American history, you don’t understand U.S. history. I think it’s very hard to be a good student without understanding our collective history. To me, it’s foundational education,” Majhor said.

While Marquette doesn’t currently have an Indigenous studies program, neighboring institutions UW-Milwaukee and UW-Madison do.

“I think it is important for all students to take an American Indian Studies class so they can learn about the people who have long called this land home. A history and contemporary presence that has always been challenged, hidden, ignored, overlooked, and erased,” Kasey Keeler, associate professor American Indian Studies at UW-Madison, said in an email.

But teaching these courses doesn’t come without its challenges. Both Keeler and Majhor said that the majority of students come in with very little knowledge about Indigenous history and contemporary issues.

“Though this isn’t necessarily bad, it does show me how little education students have had about American Indians, American Indian history, and American Indians today in their K-12 education. There is a big gap in knowledge and awareness. So, it is difficult, if not impossible, to fill that gap in one 15-week college course,” Keeler said in an email.

Here at Marquette, Majhor said that students’ lack of prior education can cause certain reactions, but is generally a positive experience.

“The difficulty comes when students learn about these histories and sometimes there’s an emotional reaction of guilt or wondering, ‘why wasn’t I taught this?’ There’s sort of a disappointment in their own education that has left these gaps on racial and ethnic issues, but that’s also rewarding because you see real growth,” Majhor said.

Though challenges may arise when teaching on these topics, Keeler said it helps students to gain new perspectives that they may have not prior to taking such classes.

“By examining Native history and contemporary issues, students are provided a more well-rounded education. Centering Native voices provide a more nuanced and accurate history than what many grew up with, often a very whitewashed version of history,” Keeler said in an email. “By taking classes that focus on contemporary issues American Indians face, it reminds students that Native people exist contemporarily, not just has historical figures.”

This story was written by Megan Woolard. She can be reached at megan.woolard@marquette.edu