“This month is finally some recognition of the culture that was here long before what we have today,” Cameron Fronczak, a sophomore in the College of Arts & Sciences and a Marquette Indigeneity Lab research student said.

November is Native American Heritage Month, which was adopted in 1990 to acknowledge Indigenous people’s ancestry, traditions and contributions made throughout history.

“There is a need for Native American Heritage Month because so much of Native heritage has been intentionally destroyed, yet we proceed to preach inclusivity and diversity and claim to uplift everyone’s cultural background,” Fronczak said.

Many Indigenous people have used this month to work towards being accurately recognized in society.

“There’s not a lot of talk in our education today about the people who were here first in America,” Rebecca DeBoer, a senior in the College of Education, said.

Many Indigenous people find the holiday Thanksgiving controversial. By some, it’s recognized as a National Day of Mourning to educate Americans about the history of Thanksgiving.

The National Day of Mourning is a day of remembrance as well as a protest of the oppression Native American people face. It works to honor Native American ancestors and raise awareness of the struggles of Native people.

“It’s hard to hear people talk about and believe that Thanksgiving was when the Native Americans and pilgrims became friends when so many Indigenous lives were lost at the hands of the colonists,” Fronczak said.

The story people are typically told is that friendly Native Americans taught the colonists how to survive in the New World and they sat down for a peaceful dinner. But many see it as the day the colonists stole the land from the Native Americans.

“No matter the month, Indigenous concerns weigh heavy,” Jacqueline Schram, director of public affairs and special assistant for Native American affairs, said. “There isn’t nearly enough room in one month out of the year to tell all these stories in a meaningful way.”

Wisconsin is home to 11 federally recognized tribes: Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Ho-Chunk Nation, Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Menominee Tribe of Wisconsin, Oneida Nation, Forest County Potawatomi, Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, St. Croix Chippewa, Sokaogon Chippewa and Stockbridge-Munsee.

DeBoer believes this month gives these tribes the opportunity to be proud of their culture.

“People have started taking hold of being Native American and trying to correct history and also just trying to be proud of who they are and where they came from,” DeBoer said.

0.2% of undergraduate Marquette students enrolled full-time for the fall 2021 semester are Native American.

The Marquette Indigeneity Lab was created “to support the experiential learning of Marquette’s Indigenous undergraduate students through high-impact, faculty-mentored interdisciplinary undergraduate research.”

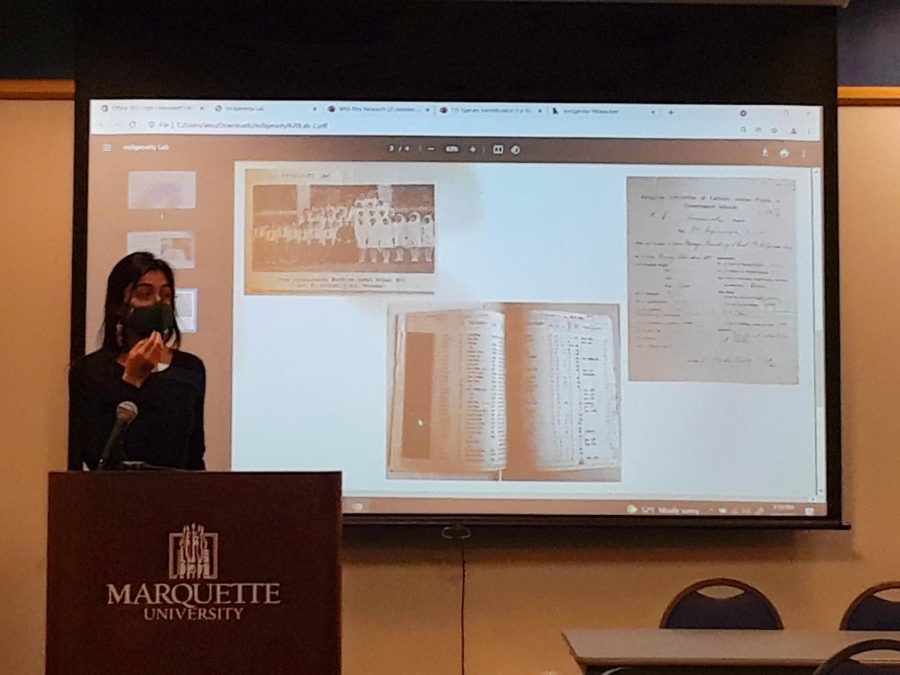

Marquette’s Soup with Substance, a lunchtime speaker series on topics of justice and peace, showcased the research projects of five undergraduate students in “The Marquette Indigeneity Lab – Making the Invisible, Visible” Nov. 10.

The lab allowed students to shed light on Indigenous issues such as Catholic Indian boarding schools.

From the late 1800s to the 1970s, Native American children were taken from their homes and placed in boarding schools by religious organizations to assimilate Native American children into American culture.

“I know this is a hard topic to talk about for some people because of all the generational trauma but I’m trying to look at the positives of how we can use this information at Marquette to be better for Indigenous people because this concerns us all,” DeBoer said at the panel.

One of the research projects by Fronczak and Clare Camblin, a junior in the College of Communication, worked to create a data visualization map of Indigenous Milwaukee.

“Students picked a site that interested them and wrote about it and its history and depth and then that’s what we broke down and took the Indigenous parts of their essay and wrote it down into a readable page so it would be easy to reference in the map,” Camblin said at the panel.

Danielle Barrett, a junior in the College of Arts & Sciences, and Will Egan-Waukau, a senior in the College of Arts & Sciences and president of the Native American Student Association studied the potential for reintroducing wild rice seed varieties to the Menomonee River Valley.

“Wild rice was a sacred finding of Native people because they followed a prophecy where they knew they were in their homeland when they found food that grew in the water. From there, it became a very sacred and precious food to them and then colonizers came and found it and they decided to domesticate it,” Barrett said at the panel. “Because of this wild rice has disappeared for native people.”

Marquette has two more events planned for the remainder of Native American Heritage Month.

Students will get the opportunity to attend “Menominee Black Ash Basketmaking: Voices, Traditions and Preservation” Nov. 22 where two basket makers, who are leading the effort to harvest black ash trees to preserve materials for their community’s future generations, will lead an in-person demonstration.

Marquette Men’s Basketball has partnered with N7, an organization committed to getting youth in Native American and Aboriginal communities moving so they can lead healthier, happier and more successful lives. At the men’s Basketball Game Nov. 27, players will wear turquoise jerseys because turquoise holds symbolic prestige and power in many Native American communities.

This story was written by Bailey Striepling. She can be reached at bailey.striepling@marquette.edu.