Since the NCAA’s inception in 1906, student-athletes could not earn any profit off of their performance or popularity.

But two years ago, that all changed.

Marquette law professor Matt Mitten, who also serves as the executive director of the National Sports Law Institute, mentioned the change took place when an NCAA Working Group proposed that all three divisions should have a name, image and likeness policy, commonly referred to as NIL.

Through the mixture of new state laws and NCAA rule changes, this significant shift in the college sports empire was etched into its 115-year-old history July 1 of this year.

Marquette athletic director Bill Scholl said it didn’t come as a surprise when the NCAA moved forward with NIL plans, but the uncertainty of specific guidelines leaves a complex situation.

“It was hard to be ready for our student-athletes on July 1 because as of June 30, we didn’t know what the rules were going to be,” Scholl said. “It’s a significant change in direction and to have that change occur with very little time to react was just more frustrating than anything else.”

No state guidance

As of Sept. 18, 28 of the 50 states in the United States have passed NIL legislation. Out of those 28 states, only 14 went into effect directly July 1.

Wisconsin falls into the minority category of no state law for NIL.

Mitten said per the NCAA Board of Governors’ policy, the states with no NIL law enforce the policy on a school-by-school basis.

Due to this, Scholl said Marquette had to adopt the NCAA’s Emergency Legislation.

Scholl said the legislation that was announced June 30 was not the only plan the NCAA originally proposed and the one that he and his team were preparing for.

He said the main difference between the two was the original version consisted of more guardrails and principles to help give an athletic department direction on how to handle certain situations if they came up.

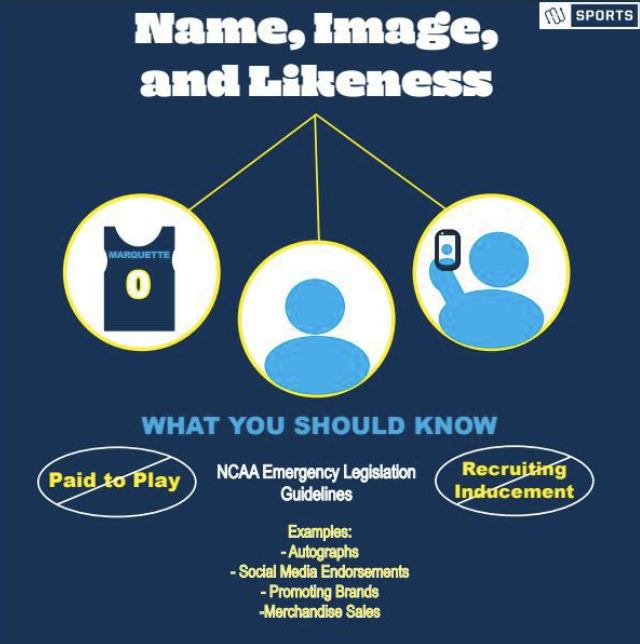

Within the legislation that was passed, there are just two guidelines — athletes can’t be paid to play, and NIL cannot be used as a recruiting inducement — that need to be followed.

Scholl said that although state direction would have made the initial transition smoother, it is only a short-term solution.

“In all honesty, the long term is some kind of a national solution so all 50 states are playing by the same rule,” Scholl said. “I hope we can get to a spot where we maybe have congressional legislation so that we’re not all playing by different sets of rules.”

Mitten said the focus of a national solution or national NIL rights law was a topic of conversation when he spoke in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee in July 2020.

Executive associate athletic director Danielle Josetti, who in charge of Marquette’s NIL policy, said although a state law would have given her some framework to work with, she prefers the way it currently stands.

“I feel like our policy is more student-athlete friendly than some of our peers with state legislation because we don’t have the same parameters that they do,” Josetti said.

Do’s and don’ts

In addition to the two rules set by the NCAA, Josetti said there are some additional excluded categories in Marquette’s policy that coincide with being a Jesuit university.

“They also can’t use Marquette’s mark and logo without entering into an agreement with the university,” Josetti said. “They can’t miss class and they can’t miss team activities for NIL activities.”

Scholl said while drafting Marquette’s policy, there were some discussions with the BIG EAST, but the policy in place is one that works for Marquette.

Most notably, the involvement of the BIG EAST was for the use of the conference-owned intellectual property, specifically with Fox Sports footage.

Using footage from a broadcast or sporting event for revenue was one thing Mitten spoke against in front of the Commerce Committee this past summer.

“That would be a revenue sharing model,” Mitten said. “I don’t believe in that and don’t want to see college sports professionalized. If student-athletes were given a share of the broadcast revenues or any other revenues, that would cross the line.”

When an athlete does make an NIL deal, Josetti said they need to report it, but it is not mandatory to do it in advance.

“It’s pretty liberal,” Josetti said. “(It is) pretty student-athlete friendly because we want them to be able to take advantage of it knowing that it could get tightened up a year or so from now.”

Mitten said schools like Marquette can implement a rule restricting a student-athlete from entering an NIL deal with a particular company. An example would be a sports gambling company.

Coinciding from the NCAA rule of no pay to play, Mitten said a school can’t enter a deal with their student-athlete(s) as the money is supposed to come from third parties.

“What the NCAA would like to do is let student-athletes earn as much income as they can subject to the parameters of their respective state law … to maintain the amateur nature of college sports,” Mitten said.

Education

Mitten said there is a fine line regarding the amount of involvement a school can have with an athlete when making a deal.

“The school is not supposed to be in the middle of arranging things because once they start doing that, then that would violate one of the guidelines,” Mitten said.

Scholl said the fine line of not giving advice to their athletes is a tricky situation for universities to find themselves in.

“We’re not telling them to do one thing and the other, we’re just telling (them) please be strategic and be thoughtful,” Scholl said.

One way Marquette Athletics has approached being involved is providing resources and education to their student-athletes.

“From a student-athlete’s perspective, if you’re suddenly getting paid to do something, there’s taxes, there’s contracts, there’s duties you have to honor and fulfill. There’s a lot of things that 18-to-22-year-olds might not have thought about,” Scholl said.

Scholl said with the department getting a head start on educating their student-athletes by partnering with Influencer last summer, it gave everyone a head start.

“Companies like Influencer have been very valuable in terms of helping to educate student-athletes (with) a lot of the issues, the legal ramifications and tax ramifications of how to build a brand,” Scholl said.

Josetti mentioned along with Marquette’s sports properties group, Learfield, the department is providing resources like Lammi Sports Management, a Milwaukee-based national sports marketing agency.

“Marquette Athletics is not going to pay anybody for an appearance; however, we are able to provide that service to our athletes,” Josetti said. “It doesn’t benefit our department, but it’s a service we can provide to them.”

Mitten said that while schools aren’t forbidden to be in the middle of organizing deals, it is a dangerous area to become involved in.

“What Title IX requires is not only proportionate equal athletic participation and opportunities, but equal treatment and benefits,” Mitten said. “That’s where the education, the branding and how to build a social media presence comes into play.”

Branding

These days, one’s presence on social media is sometimes all it takes to become famous. For college student-athletes today, they can cash in on their fame and brand for NIL deals.

“This is something that should have been passed a long time ago, even probably pre-social media,” Josetti said. “But now in the social media area with influencer lifestyle, it’s awesome.”

Athletes can now use platforms like TikTok or promoting brands and clothes on Instagram, which Josetti said will help Marquette’s non-basketball student-athletes.

“It’s awesome they can profit off of being who they are on social media,” Josetti said.

Clemson football tight end Braden Galloway is an example of an athlete using his social media following to create a brand.

Galloway, who has 161,000 Instagram followers and more than 412,000 followers on TikTok, signed a significant deal with The Familie, an agency working across sports, music, art and media, based on his influence across social media.

Mitten believes this will bode well for the non-basketball student athletes due to the university’s alumni base.

“At a place like Marquette, which has a very loyal alumni base, for the alumni who played sports other than basketball, this is an opportunity for them to really provide a level of measure of economic support directly to student-athletes that they couldn’t do in the past,” Mitten said.

Scholl acknowledged when it comes to an athlete’s brand, there might be a gender inequity favoring male student-athletes, but he hopes NIL is an opportunity for the lesser-known sports to have an opportunity to gain recognition.

College of Communication associate professor of strategic communication James Pokrywczynski said understanding if one has a brand and what it looks like is a key first step for athletes.

Mitten said he believes NIL will play a bigger role in the NCAA transfer portal, especially with the NCAA passing a one-time transfer waiver this summer.

Pokrywczynski echoed Mitten’s thoughts, emphasizing that a state’s NIL condition and conference TV coverage can impact a student-athlete’s decision to transfer as it can impact their brand.

“Visibility is everything in your brand,” Pokrywczynski said. “It gets back to what’s the audience of followers that you are attracting and it’s the same thing with being on TV.”

He said there are pros and cons to being seen on TV, as an athlete’s brand can be impacted negatively if they don’t perform at a high level.

Josetti said in terms of releasing when and if Marquette will publicly release their NIL policy, it will depend on how the national landscape plays out.

As for the number of deals already done, Josetti said it isn’t in the hundreds just yet.

“We do have a couple of high profile student-athletes that have really big deals, which I’m envious of for them, but it’s more trade right now,” Josetti said.

What’s to come

When asked what the impact of NIL can be five or 10 years down the road, Mitten circled back to one thing.

“I would hope that college sports doesn’t shift to a professionalized minor league sports level,” Mitten said.

Mitten said he hopes there isn’t a loss in focus on earning a degree from the NIL.

“That is one of the things traditionally people would say distinguishes NCAA football from NFL football,” Mitten said. “They have a unique opportunity to earn a degree that is probably going to help them earn an income stream much higher than the small handful of athletes who could by playing a professional sport. So I hope that doesn’t go away.”

Mitten said otherwise, he can see NIL becoming a positive thing, most notably with those athletes who are in the bubble of whether to stay in college or pursue a path of having a professional career.

“Let’s say you’re a year away from your degree, you played three years of football and you’re eligible to go into the NFL but you might be a late round draft check or free agent,” Mitten said. “Those athletes will hopefully have the incentive to stay in college one more year, develop their skills, get a degree, and earn some extra money from NIL rights. So I could see that as a real positive thing there.”

While Marquette does not sponsor football, the principles remain the same across the entire sporting landscape.

Until there is a national solution from Congress, Mitten has one additional hope.

“It’s an entirely new world and I hope we can keep the best of college sports without losing the best of college sports,” Mitten said.

This article was written by John Leuzzi. He can be reached at john.leuzzi@marquette.edu or on Twitter @JohnLeuzziMU.