As Milwaukee businesses, classrooms and sports stadiums are all starting to open their long-closed doors to the public, the availability of various vaccines in recent weeks at locations like the Wisconsin Center have played a large part in getting life back to normal.

More than 27.5% of Wisconsin residents are fully vaccinated, with 3,870,751 total doses administered, as of April 18. Endless social media posts of vaccine cards aside, there are some students who have protests about getting the vaccine. But what information is available to aid or abate these anxieties?

Do the COVID-19 vaccines have long-term effects?

Jaque Contreras Saavedra, a Junior in the College of Engineering, was initially on the fence about getting vaccinated.

Contreras Saavedra, despite her concerns, said that ultimately she decided to get vaccinated because “the pros outweigh the cons,” but this doesn’t change the fact that she was and is worried.

“At first I had a lot of uncertainty and doubts about getting vaccinated because I was just worried about the lack of research about the long-term effects … honestly it is still a worry of mine,” Contreras Saavedra said.

While Contreras Saavedra’s long-term worries are not uncommon, there is evidence to suggest that long-term effects are highly unlikely.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s website, “Vaccine monitoring has historically shown that if side effects are going to happen, they generally happen within six weeks of receiving a vaccine dose.” as for short term side effects, these are more common and include: swelling, redness and pain at the injection site, fever, headache, tiredness, muscle pain, chills and nausea.

It was because of this information that the Food and Drug Administration made the decision to require each of the authorized COVID-19 vaccines to be studied for at least two months — or eight weeks — after the final dose to ensure there were no complications. This is also why the CDC states that long-term side effects are unlikely, as “these vaccines will undergo the most intensive safety monitoring in U.S. history.”

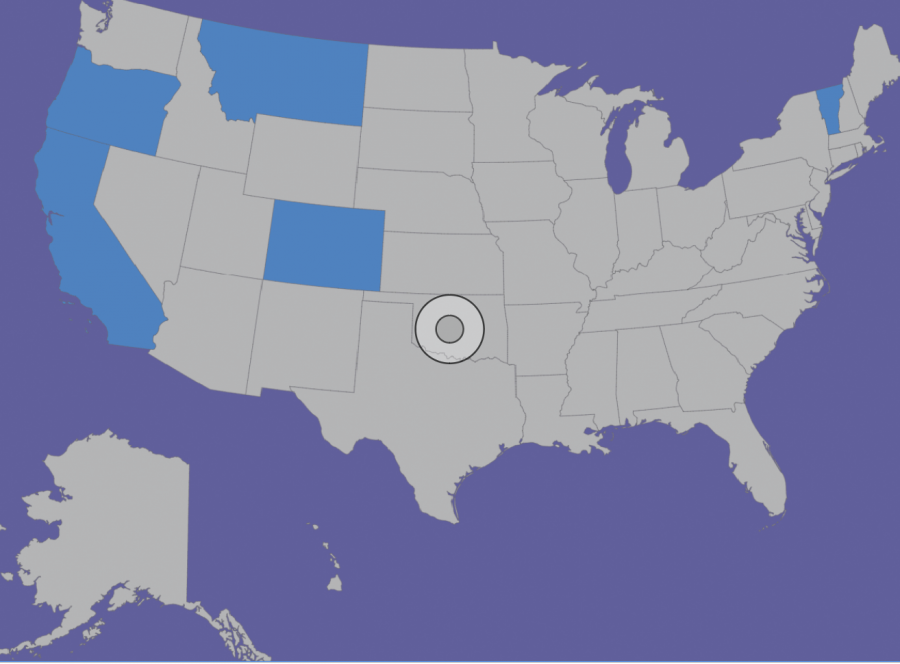

The three most prominent vaccines available in the United States are Pfizer, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson, according to the CDC.

As for what type of vaccines all of the three major options are; the Moderna and Pfizer options are both mRNA vaccines which teach our cells how to make a protein—or even just a piece of a protein—that triggers an immune response inside our bodies.

The Johnson & Johnson option is different in that it is a vector vaccine. The vector vaccine will enter a cell in our bodies and then use the cell’s machinery to produce a harmless piece of the virus that causes COVID-19 and in turn an immunity.

As for how a vaccine does get approved, and how math and science can assure its effectiveness and safety, Henry Kranendonk, a professor of statistics at Marquette, gave some clarifications.

“It’s important for us to realize the process (of how a vaccine gets approved) itself. If you follow the statistics, then when more data is being collected and analyzed, we can realize that getting the vaccine is the safest thing to do,” Kranendonk said about how a lack of complications suggests that the vaccine is safe.

Kranendonk emphasized that science is sometimes “fluid,” or changing, and because of that statistics can help determine the safety of certain vaccines because seeing numbers can be more assuring.

He also mentioned the recent halt of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine distribution at federal sites due to the risk of blood clots. The more accessible a vaccine becomes, the larger the sample size becomes, and you could see rare adverse effects, he said.

Do the vaccines use fetal tissue?

Some students are not worried about the science associated with the vaccine, but rather the moral questions that stem from its production and use.

Ellen Sharp, a Sophomore in the College of Education, is a contributing writer for the Eagle Free Press — a conservative publication run by five Marquette students.

It was there she published an article questioning the morality of the COVID-19 vaccines, specifically the Johnson & Johnson option.

She said her worries were predicated on her Catholic belief that abortions are immoral and the use of fetal cell lines in the vaccines is also immoral.

According to Nebraska Medicine, the COVID-19 vaccines do not contain aborted fetal cells, but cell lines. The difference is that rather than being direct fetal cell tissue, a fetal cell line is grown in a lab and derives from cells taken from elective abortions in the 1970s and 80s.

Sharp further expressed worries about the use of the fetal cell lines in the stages of vaccine development, confirmation and production.

“Pfizer or Moderna are okay (morally) because they only use it (fetal cell lines) one (development) out of the three stages…However, the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, which I am not for, uses these fetal cell lines in all three of their stages,” Sharp said.

In December the Catholic Church officially announced, in response to anxieties about the fetal cell lines, that getting the COVID-19 vaccine is morally OK. In January Pope Francis received doses of the Pfizer vaccine, and last month the Catholic Church announced that it is OK to get the Johnson & Johnson vaccine specifically.

In a January interview, Pope Francis has already made comments encouraging people to get vaccinated, “I believe that morally everyone must take the vaccine,” justifying his statement by explaining, “It is the moral choice because it is about your life but also the lives of others.”

Additionally, other common vaccines like the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine, Hepatitis A vaccines, Varicella (chickenpox) vaccine, Zoster (shingles) vaccine and the rabies vaccine all use fetal cell lines.

In response to this, Sharp said that she still has worries about the issue as she is “passionate about pro-life,” but Sharp did eventually say that she encourages everyone to get any COVID-19 vaccine as it is the safest thing for everyone: She just prefers the Johnson & Johnson vaccine be avoided.

Are vaccines effective against variants?

Alex DeSimone, a first-year in the College of Arts & Sciences, said he does not want to get a vaccine.

Like Sharp, he is also worried about the morality of the vaccines, but he said his biggest anxieties stem from whether it will work against variants. He cited complications in South Africa with how the various vaccines are adapting to a new strain of COVID-19.

“They started getting the vaccine (in South Africa) — I’m not sure if it was Pfizer or which one it was —but if you look at the people who got vaccinated, and people who got coronavirus after they were vaccinated, you see that this rare strain is actually making people more susceptible to getting coronavirus, for that reason I’m going to pass on it,” DeSimone said.

The strain in South Africa that DeSimone is talking about is the B.1.351 strain, which is regarded by experts as one of the most challenging variants to date. The idea that vaccines are ineffective against this particular strain isn’t quite true, however.

According to a New York Times article citing a large study of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in South Africa, it was found that “it (the Johnson & Johnson vaccine) was about 85% effective at preventing severe disease, and lowered risk for mild to moderate disease by 64%.”

In comparison, AstraZeneca, the most common COVID-19 vaccine in South Africa, is believed to “not do much to protect against mild illness caused by B.1.351, but scientists said they believed the vaccine might protect against more severe cases, based on the immune responses.”

It is important to note here that the term efficacy is not as simple as it may seem. For example, 90% efficacy does not mean 10% of people will be infected. This number is determined by how much better the vaccinated group in a study performs when compared to the unvaccinated group.

If both groups have 100 people in them and a vaccine has 90% efficacy, this does not mean that 10 vaccinated people got infected. Rather, this means that if the unvaccinated group has 10 people get infected and to achieve 90% efficacy the vaccinated group must only have one person become ill.

When looking at the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines’ effectiveness against the South African strain, it is believed, according to the previous NYT article, that those vaccines could reduce risk by 60-70%, which Adi Stern, the study’s senior author and a professor at the Shmunis School of Biomedicine and Cancer Research at Tel Aviv University, said is still an “extremely high” efficacy.

DeSimone also expressed befuddlement at why the vaccines are not fully effective. A USA Today article states that is a combination of two main things: bad luck and variants.

Is the vaccine FDA approved?

Grace Armstrong, A Junior studying English Education at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, is already vaccinated but has only one concern, that the COVID-19 vaccines are not Food and Drug Administration approved.

While none of the three main vaccines — Pfizer, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson — are approved, all three have been given emergency use authorizations.

According to the FDA website, emergency use authorizations allow the “FDA to help strengthen the nation’s public health protections against chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) threats including infectious diseases, by facilitating the availability and use of medical countermeasures (MCMs) needed during public health emergencies.”

To get an FDA emergency use authorization the website states “for an EUA to be issued for a vaccine, for which there is adequate manufacturing information to ensure quality and consistency, FDA must determine that the known and potential benefits outweigh the known and potential risks of the vaccine.”

It has been reported by ABC that Moderna has released the results of its vaccine trial after six months, which will allow it to seek full FDA approval, and is an indicator that it may be able to get said approval.

Armstrong did say that she has confidence in the vaccine, however, and said that there are other things that we put in our body which she is more worried about.

“I’ll hear people say that they are worried about what’s in the vaccine and then see those same people do hard drugs at a party,” Armstrong said in response to speculation about what is in the vaccine.

There is definitive and clear information about what is in each vaccine, and it is posted on the CDC website.

This story was written by Beck Andrew Salgado. He can be reached at beck.salgado@marquette.edu.