In 2015, Marquette University shifted from having the campus protected by security guards to adopting its own private police force of certified and armed police officers.

Beyond upholding state and local laws, Marquette University Police Department is an organ of the university hierarchy; as a private organization, MUPD responds to direction from the administration itself.

State law had to be passed that stated Marquette could start a department. This law is the 2013 Wisconsin Act 265. This law gave university officers the same rights as law enforcement officers employed by the city of Milwaukee as long as the officers met the state of Wisconsin certification requirements, written policies regarding law enforcement activities were adopted, and liability insurance was maintained.

Today, the university has more than 80 trained safety professionals, including 44 uniformed police officers who patrol campus and several blocks beyond into the Milwaukee community.

Jeffery Kranz, assistant chief of MUPD, said that there was no singular triggering event that lead to the shift from having a department of public safety to a police department. Rather, he said there was a build-up of general safety concerns. While the department of public safety provided a qualified level of security to the campus community, Kranz recalled increasing complaints due to a perceived lack of security guard efficiency, a consequence of limited time and resources.

“Just being private security really limited their ability to act … what was taking a lot of time was calling Milwaukee Police Department to come with their ability to police to handle a problem. A simple call could take two or three hours because a simple call is not a high priority call for Milwaukee PD … they would have to wait quite a while to get a police response here.” Kranz stated.

Before 2015, the university had a public safety department that provided security to the campus community. Public safety was staffed with armed security guards that handled responsibilities such as building security, maintaining safety of the campus populace and responding to incidents on campus.

Thomas Hammer, associate law professor, said public safety officers faced serious limitations.

“I thought, quite frankly, as public safety departments go, ours was a very good one,” Hammer said. “But there are limitations on what a public safety office can do. They aren’t police officers.”

Kranz was brought onto campus safety in 2014 to help with the development of the police force. After working for Milwaukee Police Department for 26 years, Kranz recognized MUPD would need to adopt a slightly different approach to policing in order to cultivate a trusting campus community. MUPD has a team of about 44 sworn officers, compared to the 800 officers that serve with MPD. Kranz presented the department size as a strength.

“We always said from the beginning that we wanted to make a small town police department in a urban setting … When you call MPD you get this random cop that divides their attention throughout their district and you don’t really know who it is… we wanted you to be able to called Officer Jodie [for example] and know who she is and when she comes to take your call for service you are comfortable talking to her and if that problem persists it’s somebody you can personally reach out to.” Kranz said.

Michael O’Hear, professor of law and member of the MUPD advisory board, said he believes MUPD provides for campus in ways the Milwaukee Police Department could not.

“If you have a police department that is dedicated mostly to serving a campus community, the officers will be much more knowledgeable about the campus and groups on campus and effective ways of interacting with college students and other people that live and work on a college campus.” O’Hear said.

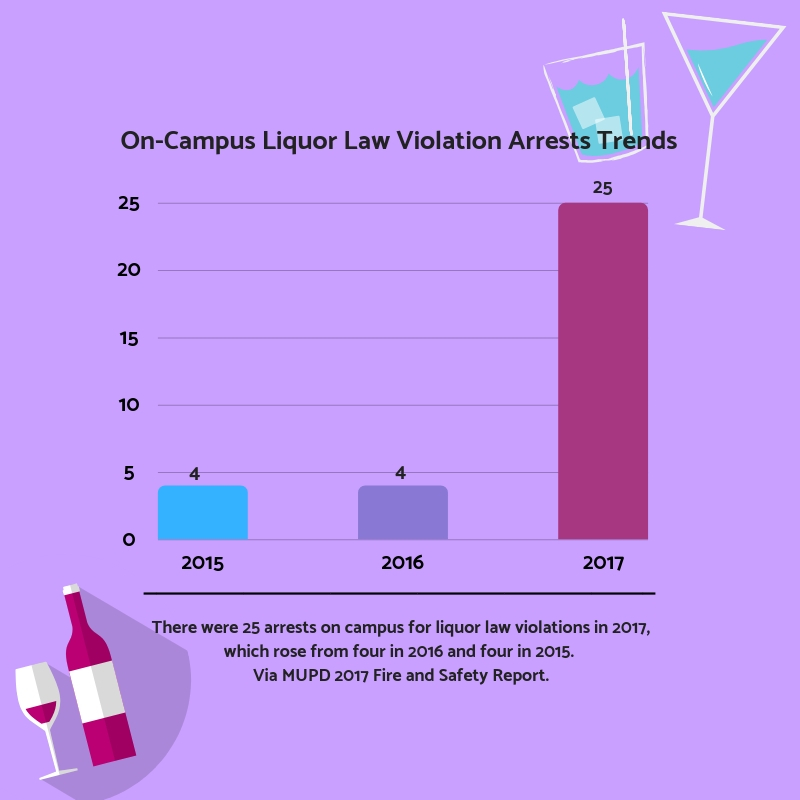

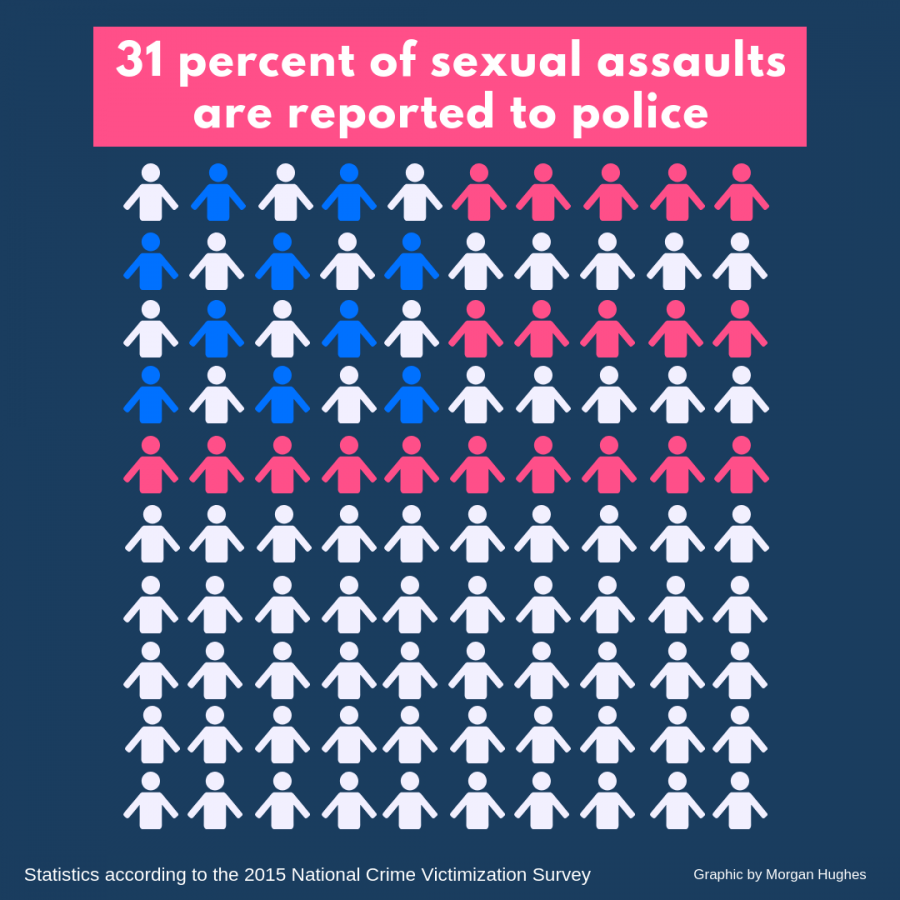

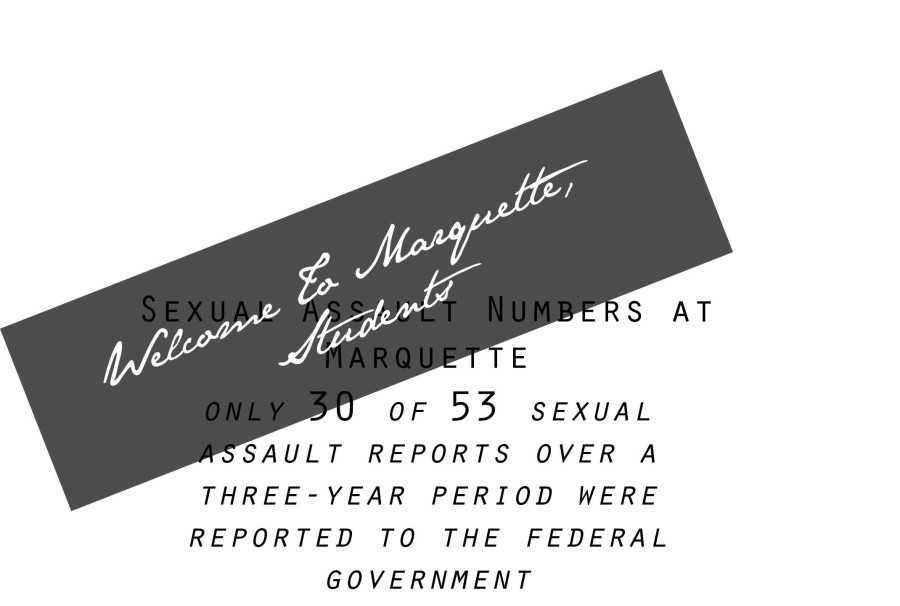

According to data found in MUPD’s Annual Security and Fire Safety Report from 2018 and 2019 total criminal offenses on Marquette University’s main campus have declined between the years 2015-2018. In 2015, the total number of criminal offenses was 41. In 2018, the total number of criminal offenses was 24. Categories that were looked at in these reports include: murder, negligent manslaughter, rape, fondling, incest, statutory rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, motor vehicle theft and arson.

“When I was serving as the chair of the advisory board, I would regularly get reports on crime in the area and there was a precipitous decline of serious crime in the area after the formation of MUPD. I think there was a direct cause and effect relationship with the creation of the department and decline in crime,” Hammer said.

An advisory board has been established to ensure MUPD is both accountable and transparent in their workings with the campus community. This board consists of five members: the head chair, a faculty member, a student member, a community member and a staff member. Michael O’Hear, Meghan Stroshine, Meredith Gillespie, Keith Stanley, and Jenna Goeb make up the current board, respectively.

“MUPD’s advisory board is just that, an advisory board. There is really no authority over MUPD,” O’Hear said, as current chair of the advisory board. “I think the board is playing a constructive role, but it is important to realize the board doesn’t have any actual authority beyond just being able to provide input which the chief might or might not do anything with.”

Hammer, who served as chair of the advisory board before O’Hear, also recognizes the limited power the advisory board can have on the department — but he did not perceive it as a shortcoming.

“I thought we had an excellent relationship with the leader of the department. I think the leadership of the department took seriously the role of the advisory board and provided us with any information we wanted about what was of interest to us,” Hammer asserted.

Private entities are not required to meet community policing standards, which emphasize collaboration with community members. Collaboration with community members can be an important step in identifying problems and finding solutions and also helps communities feel heard by law enforcement. Marquette ‘s advisory board is an attempt at involving community in creating public safety goals.

Private police are also not required to respond to Freedom of Information Act requests. The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) gives the public the right to request access to records from any federal agency. It is often described as the law that keeps citizens in the know about their government. Many universities with private departments only send campus crime alerts to the campus community and are not required to release records directly to the public.

Given that Marquette intended for MUPD to remain a private organization that responds to internal authority, the state of Wisconsin had to give permission for it to become a police department. Many campus police forces in Wisconsin, specifically the University of Wisconsin system, are not private institutions and, therefore, did not have to undergo the same processes MUPD did to become established.

“We looked at UW-Milwaukee and UW-Madison and just saw how their operations were … they are still a part of a governmental body, the unique thing about us is that we are private. We don’t have a municipality or state government that oversees us.” Kranz said.

There are powers that private departments have that should make universities question whether private police forces make campus and surrounding communities safer. For one, private departments, including MUPD, have patrol and arrest jurisdictions that extend beyond campus boundaries. Those who oppose the use of private departments on college campuses argue that this extended jurisdiction could result in strained relationships between communities, police, and universities, particularly if the surrounding areas already experience high rates of policing. Surrounding communities might also feel threatened by private departments because their primary purpose is to serve their university and the department is not held accountable to that surrounding community, even though they hold a police presence over them. A map of MUPD’s patrol area can be found on their website.

The Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act was signed in 1990. The Clery Act requires institutions of higher education that participate in federal financial aid programs to keep and disclose information about crime on and near their campus, and it applies to private organizations. The act requires institutions to publish an annual campus security report that documents specified campus crime statistics from the previous three years.

MUPD’s annual report can be found on their website. The act also requires the maintenance of a timely public log of all crimes reported and known to campus law enforcement officials. The department in question must submit a timely warning of crimes that represent a threat to student or employee safety, which is accomplished through MUPD safety alerts. The United States Department of Education is charged with enforcing the Clery Act and if an institution is found to have violated the act, there can be penalties up to $35,000 per violation and the institution may be suspended from participating in federal student aid programs.

The privatization of MUPD has brought up questions about hierarchy of power, its responsibilities and how relationships have changed in its transition from campus safety. This exploration of Marquette’s police system has become particularly pertinent in light of calls to defund the police across the country, and even among universities.

This is the first of a series in which the projects desk will take a look at MUPD’s range of responsibility and relationship to students and staff in context of COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter protests that were sparked by the death of George Floyd.

This story was written by Maria Crenshaw. She can be reached at maria.crenshaw@marquette.edu.