At the beginning of every class they taught, Jones*, a professor in the College of Arts & Sciences, told their students one thing: “I have the greatest job in the world.”

Jones stopped saying that this year.

Jones* is a professor at Marquette University. Jones’ request to remain anonymous was granted due to the sensitive nature of this article and the risk of losing their job.

Along with numerous tenured and non-tenured track professors, Jones found themself disheartened and demoralized by the announcement of 225 to 300-plus potential layoffs in the wake of an anticipated 45 million dollar budget deficit extending to fiscal year 2022 and beyond. Roughly 1/5th of all campus faculty and academic staff could be cut.

“The entire reason we became professors is for the students,” Jones said. “I get to do what I love, and work with students to do that.”

But Jones said they do not love what they do anymore because of Marquette.

The shortfall Marquette is facing is based on known and exacerbated losses due to the COVID-19 pandemic, along with an enrollment decline, Provost Kimo Ah Yun relayed in an email to the Marquette Wire.

“We are making these decisions precisely because the future of higher education is at an inflection point,” Ah Yun said in an email. “The demographic projections have prepared us for that and the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated some of the issues we were already preparing for.”

Ah Yun stressed that no decisions on faculty and academic staff reductions have yet been implemented.

But faculty and academic staff expressed anxieties regarding the utilization of demographic models that could be blind to change, a potential hollowing of the humanities and a conspicuous absence of transparency from the administration resulting from suppressed unionization efforts.

“These are 400 human beings. If you kick them out of academia, you’re kicking them out of a way of life,” Jones said. “The president speaks of sacrifice, which to me reeks of paternalism. There’s been no talk of the individuals they are cutting, the families whose lives are affected, and to me that’s so disturbing.”

This is not the first time the Marquette administration has grappled with the issue of long-term financial sustainability. In a campus-wide letter penned by Lovell in 2019, Marquette announced it would lay off 24 employees — its first workplace reduction since the mid-1990s. Citing an anticipated decline of 15 to 25 percent of college-aged students by 2026, Lovell appeared to present Wisconsin and the broader Midwest as ground-zero for enrollment depreciation.

The model utilized by the administration to project this demographic downturn comes from economist Nathan Grawe, of Carleton College in Minnesota. In his book, “Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education,” Grawe tracks the drop in birth-rate to the 2008 fiscal recession.

Grawe’s grim forecast model, and Marquette’s implementation of the model to guide budget cuts, has been scrutinized for its alleged prioritization of white, upper-class families. As universities and colleges — both elite and non-elite — seek to alter their historic enrollment patterns, there has been a concerted effort to attract first-generation students, minority students and adults. But some say that, with these cuts, these diversifying efforts may be consequently annulled.

“The assumption is that upper-middle class and wealthy white students are the only people that the administration seems to think of as viable students for the future,” Doe*, a professor in the College of Arts & Sciences, said. “The entire focus on racial equity is in jeopardy.”

Doe has also been provided anonymity to protect their identity.

In a 2018 interview with Inside Higher Ed, Grawe addressed these concerns.

“I hope that schools respond to the information in the model with better retention policy or new recruitment strategies and so survive or thrive despite demographic hurdles,” he said. “This would make the forecasts look wrong by putting them to good use.”

Grawe argues that closing the achievement gap across student groups remains a moral necessity for universities, citing that Hispanic Americans now attend college at a rate equivalent to the national average — a 15 percentage point increase in the last two decades. However, he mentions it may not be enough to substantially offset the imminent enrollment slump.

“Still, a 15-point increase for a subpopulation accounting for about 15 percent of the population represents an attendance increase of less than 2.5 percent for the country as a whole,” Grawe wrote in a 2019 Higher Ed Jobs article.

In 2016, Marquette launched its initiative to become a Hispanic-Serving Institution, a designation granted to two-year and four-year institutions that enroll low-income students and have an undergraduate Hispanic population of at least 25%.

Once an institution achieves HSI status, it is eligible for federal Title V funds. Marquette is currently ineligible for Title V funding because its undergraduate Hispanic population, as of the 2019 fall semester, is at 12%. Title V is a provision made by the Higher Education Act to aid institutions that enroll Hispanic and low-income students.

“Now, it suddenly seems like we’re being told that that can never be. That if Marquette changes its demographic, it can’t survive,” Gerry Canavan, associate professor of English, said.

Grawe insists that schools must look beyond admissions to amend this institutional and demographic tension. Canavan, however, expressed confusion at Marquette’s unwillingness to even consider new recruitment and investment strategies.

“I don’t understand why we think Marquette can’t adapt to the changing demographics of America,” Canavan said. “What is it that we think we can’t do? Is it that we can’t raise money for scholarships, we can’t find ways to make ourselves less dependent on (tuition and housing) money? We can’t draw in more students from Milwaukee?”

Net tuition revenue accounts for 73% of the university’s unrestricted revenue, with room and board attributing 12.2%, according to a breakdown from 2015. The total of these two components, 85.2%, depicts an institutional dependency on enrollment to support annual operations.

In the spring of 2020, Marquette issued 150 million dollars in taxable fixed rate bonds, at 1-4% interest over the next thirty years. In these bonds, Canavan identified a potential, alternative route forward.

“We could use some of those bonds to get us through the emergency now and make the structural changes we need to make over a longer, more deliberate timetable,” Canavan wrote in a follow-up email. “I’m not sure what the annual payment would be or what the terms are precisely, but the point is that it’s an option we can use that we’re not talking about, and it seems to my eye a lot safer than trying to cut 10% of the budget in one go.”

In accordance with the Marquette Faculty Handbook, non-tenured track faculty are to be cut before those who are tenured, and among the tenured, those with lesser seniority will be the first ousted. Because women and professors of color are among the most recently hired, professors worry layoffs could lead to an institutional whitening.

“According to the Faculty Handbook, they should be the first fired, which will undo all the work that we’ve done to make Marquette a more equitable place,” Doe said.

Ah Yun said that the Faculty Handbook provides guidance on how to move forward, but he is also working with the Faculty Senate.

“We are absolutely sensitive to this concern, and will take great care to ensure measures we take do not have the least impact on what we have invested in and worked so hard to build,” he said in an email to the Marquette Wire.

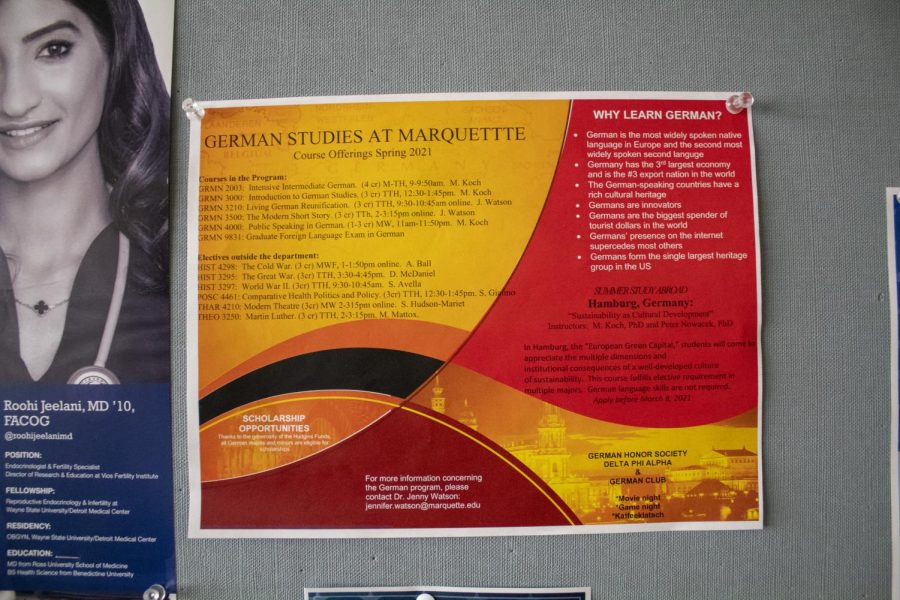

Although Ah Yun declined to reveal which departments or programs would be primarily affected in the coming layoffs, an emphasis on consolidation and profitability left some professors alarmed for both the future of the humanities and the remaining, tenured professors who will be expected to pick up the slack.

“I am concerned, as somebody who is in a humanities department at a Jesuit university, that we will be targeted,” Timothy McMahon, associate professor of history, said.

A consolidation or evisceration of the humanities would spell certain disaster for undergraduate and graduate students, Brooke McArdle, a senior in the College of Arts and Sciences, said. McArdle is double majoring in classics and history; classics is the study of ancient languages, literatures, histories and cultures.

“I don’t know where I would be without these humanities professors. They are intrinsically related to my academic success and my future. I’m incredibly grateful for them,” McArdle said. “I would really challenge Marquette to put the human element back in academia. They have the choice to be a leader in faculty appreciation, rather than … treating them as disposable.”

Almost as soon as she declared her classics major, McArdle came to a dismaying conclusion: with only one professor and one adjunct in the program, she would not be fully supported in her academic trajectory.

“Despite the talent that those professors have, being in contact with only two professors is really detrimental to academic diversity in the sense of being able to grow and take in different pedagogies,” McArdle said.

Assistant visiting professors and adjuncts have been the most influential in her experience at Marquette, McArdle said. With far fewer professors capable of providing humanistic, Jesuit pedagogy on campus, she worries students will receive poorer quality courses and scant individualized attention. Faculty layoffs are certain to impose a strain on already labor-laden professors, extending their attention far beyond the average workday.

The preliminary findings of a study conducted at Boise State University — a public doctoral institution — revealed that, on average, faculty work 61 hours a week, more than 50 percent more than the typical 40-hour work week. That time is primarily spent teaching, although a heightened insistence on administrative duties also accounts for a sizable stretch of time.

“It seems likely you’ll have less time for individual classes. That means more multiple choice assessments and less written assignments. It’s gonna mean less personalized work with students, it’s gonna mean you recycle lectures from previous semesters, it’s gonna mean you will update reading lists less often,” Barrett McCormick, professor of political science, said.

Non-tenure track faculty and graduate students at Marquette began organizing a union in the fall semester of 2018. Hefty administrative salaries compared to other employees — Marquette University pays its administrators 80 percent more than the average four-year institution — and a lack of healthcare coverage for graduate students kindled a coalition that included months of petitions, sit-ins and other forms of protest.

Unions on college campuses predominantly protect non-tenure track faculty, who work and live by renewable one-year contracts, Jones said. Constituencies organize for multivalent reasons — all pressing — ranging from better pay, job security and greater administrative transparency. The latter has become particularly pertinent in the layoff debate.

“There’s a principle called shared governance, that we are supposed to be part of these decision-making processes,” Canavan said. “It’s not simply supposed to be that faculty are presented with a plan.”

But that is exactly what the administration has done; professors contend the decision has been predetermined.

“It’s like when a parent tells their three-year-old, ‘You can choose what to wear. You can wear the red outfit, or the blue outfit.’ The choices are made — the kid isn’t going to be wearing polka dots or stripes,” Doe said. “The parents have already limited the choices, and created an illusion of control.”

The unionization movement has not been formally recognized by Marquette, leaving non-tenure track faculty and graduate students without the ability to bargain with the administration, McMahon said.

An unwillingness to meet with organizers “has implications for both quality of work and the quality of the workplace, and, frankly … prevents us from having a collective voice,” McMahon said.

Lovell seems to see faculty and employees as workers that need to be controlled, Doe said.

Morale among his colleagues has hit a low, Jones said. Because the academic job market has shrunk, it would most likely be challenging for laid-off faculty and academic staff to find new, favorable positions.

“I’m between incredibly angry, and incredibly forlorn. I’ve gone to the point where I’ve created a LinkedIn profile, I’ve tried to look for other jobs,” Jones divulged. “(But) once you’re cut, you’re most likely leaving academia. It’s not even dire, it’s cataclysmic right now.”

McArdle, as a tuition-paying member of the community, wished for a way to hold the administration accountable.

“My education is going to be significantly depreciated. I wish I felt that students had more of a voice,” McArdle said. “We need to be doing everything we can to help our professors right now.”

This story was written by Lelah Byron. She can be reached at lelah.byron@marquette.edu

Albert F Moritz • Oct 7, 2020 at 5:23 pm

A really well-written article. Provides comprehensive and thought-provoking information and perspectives. I noticed the tendency to depreciation of the humanities at Marquette in various articles, and the general emphasis, of Marquette Magazine, the alumni publication.

Albert F. Moritz

Blake C. Goldring Professor of the Arts and Society

University of Toronto

Victoria College, Northrop Frye Hall room 206

73 Queen’s Park Crescent East

Toronto, ON, M5S 1K7

afmoritz.com

B.A. 1969; M.A. 1971; Ph.D. 1975